By the Numbers: Cabo Delgado, October 2017-November 20201Figures updated as of 21 November 2020.

- Total number of organized violence events: 698

- Total number of reported fatalities from organized violence: 2,367

- Total number of reported fatalities from civilian targeting: 1,220

All ACLED data are available for download via the data export tool, and a curated Mozambique dataset is available on the Cabo Ligado home page.

Situation Summary

Government troops took the offensive in Muidumbe district last week, launching a major operation to reassert control over towns and villages that had been threatened by insurgents for nearly two weeks. Reinforcements — in the form of six armored personnel carriers, two helicopters, and a mixed group of 70 Mozambican and Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) personnel — arrived in Mueda on the night of 16 November. The offensive began the next day, and by 19 November, the pro-government website Noticias de Defesa was publishing photos of government forces in the district capital of Namacande.

One source reported intense fighting at Namacande between government and insurgent forces. Other sources, however, say that insurgents conducted a tactical retreat ahead of the government offensive, and that little actual fighting took place. Indeed, one person told reporters that the village had been free from insurgents since 16 November, before the offensive began. Nevertheless, Mozambican police chief Bernardino Rafael traveled to Namacande once it was back in government hands to publicize the victory. In his press statement, Rafael claimed that Mozambican forces had killed 16 insurgents in the offensive, although the government has put forward no evidence to back up the claim.

Insurgents remain in Muidumbe district even after the government’s reoccupation of Namacande, and DAG helicopters carried out operations against insurgent targets between Namacande and Mueda on 20 and 21 November. No casualty reports are available for those operations.

As government forces reentered Muidumbe district, more information about what insurgents had done there began to filter out. Bodies of dead civilians had been left out in the open in some villages, and district government buildings, a Catholic Church, and various homes have been destroyed. The full extent of the devastation is not yet clear, but civilians are still missing in at least 12 villages in Muidumbe.

Photos from the operation, along with Rafael’s victory tour, underline the leading role Mozambique’s police force played in the counteroffensive. While Mueda is the site of a major military base, it seems that Mozambican police, along with DAG helicopters (which are technically contracted to the police) and a substantial contingent of local militia forces, were the main units involved in the push to Namacande rather than the military. The same week, an investigative report found widespread concern among members of the military that soldiers have been passing information to the insurgents in exchange for money.

Militias and police seem to have worked closely together in the Muidumbe offensive, but in other areas of the province, tensions between local militias and government forces appear to be increasing. Militia members have accused soldiers — especially new recruits — of looting civilian property in areas they are meant to be protecting. A local militia made a formal complaint about looting to authorities in Palma town on 17 November.

New information also emerged last week concerning an earlier insurgent attack. On the night of 13 November, insurgents raided Ilha Mecungo, off the Mocimboa da Praia district coast. No one was killed, but insurgents abducted an unknown number of people and stole dried fish and other goods.

Incident Focus: Tanzania Cooperation

Just three weeks after Tanzanian forces fired rockets into Mozambique, injuring Mozambican civilians, the two countries appear to have taken a major step forward in cooperation in their counterinsurgency efforts. On 19 November, Tanzanian police announced that they had arrested several people they suspected of traveling to Mozambique to join the insurgency. Those arrested included people from Kigoma and Mwanza regions of Tanzania, as well as people from Mtwara region who allegedly collaborated with insurgents during their late October incursions into Tanzania. The police did not disclose how many had been arrested, but the Mozambican government later said that Tanzania has arrested 562 people in the wake of October’s attacks in Mtwara.

The next day, police chief Rafael was in Mtwara to sign a memorandum of understanding with his counterparts in the Tanzanian security forces. Details of the memorandum are still unclear, but two major elements of the deal have been reported. The first is that some 516 prisoners suspected of being involved with the insurgency will be extradited to Mozambique to stand trial. It is unclear how many of the 516 are among those arrested in the last month, but the group is said to include Mozambicans, Tanzanians, Somalis, Congolese, Rwandans, and Burundians. It is unclear, given the slow pace of terrorism prosecutions in Mozambique, how the Mozambican justice system will handle the sudden influx of terrorism suspects. To the extent that the prisoners are actually associated with the insurgency, however, they may provide useful intelligence for the government.

The deal also reportedly provides for joint operations between Mozambican and Tanzanian security forces. Rafael said that the two countries hoped to “control the Rovuma border” through close cooperation. It is unclear what form the joint operations will take or whether Tanzanian forces would be operating in Mozambique. Even if Tanzanian security services remained on their side of the border, however, Tanzanian logistical and reconnaissance capabilities could be important force multipliers for Mozambican operations in northern Palma and Nangade districts. However, given the recent rocket attacks — for which there has been no public explanation demanded or offered by either government — and the human rights record of Tanzanian security services generally, this level of cooperation may not be very popular among Mozambican civilians.

Government Response

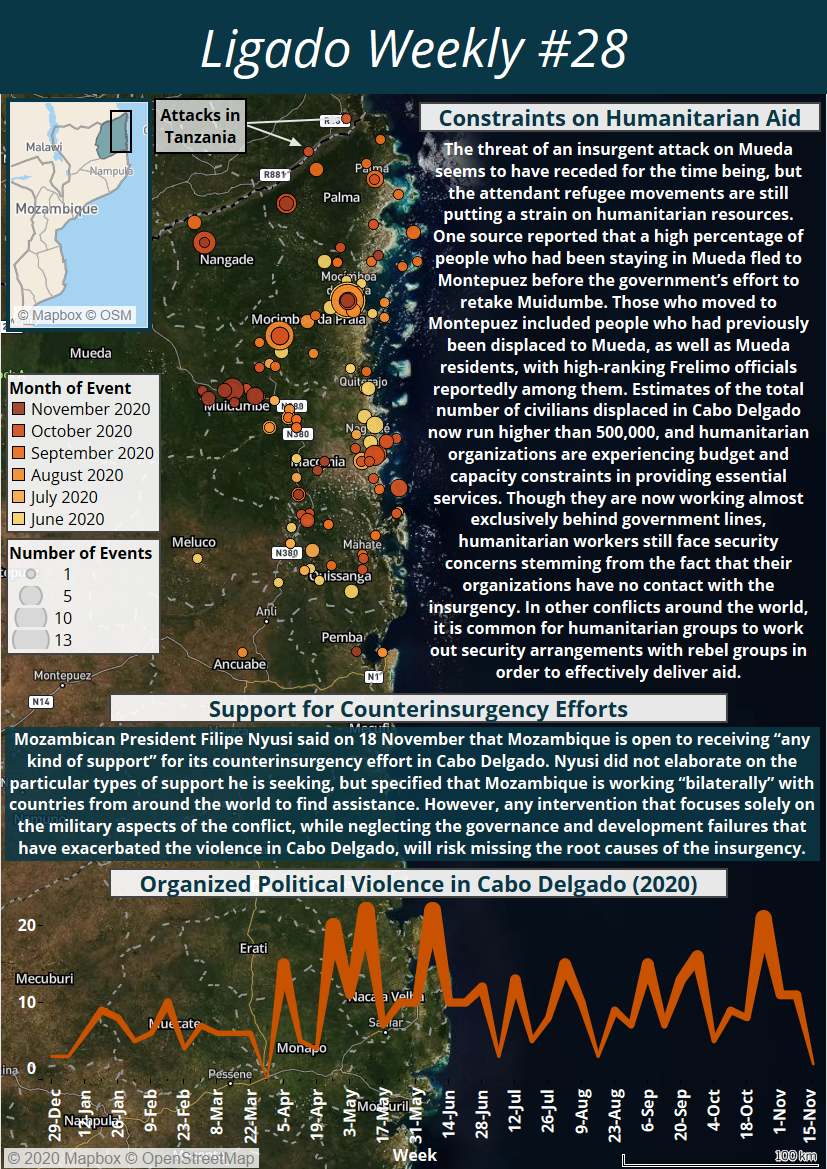

The threat of an insurgent attack on Mueda seems to have receded for the time being, but the attendant refugee movements are still putting a strain on humanitarian resources. One source reported that 70% of people who had been staying in Mueda fled to Montepuez before the government’s effort to retake Muidumbe. Those who moved to Montepuez included people who had previously been displaced to Mueda, as well as Mueda residents, with high-ranking Frelimo officials reportedly among them. Whether they will return to Mueda following last week’s government offensive remains an open question.

For refugees in Pemba, there was some good news last week as the government announced that land was being set aside near Nanjua, Ancuabe district for some of them to resettle. Cabo Delgado provincial Secretary of State Armindo Ngunga said that there were over 1,000 plots of land available for displaced people in the area, and that water infrastructure was being built to support resettlement there. There have been issues with other resettlement operations, however. Seventy displaced people due to be transported to a refugee center in Nampula province were forced to sleep outside in Nampula when their arranged transportation fell through.

Finance Minister Adriano Maleiane also announced that Mozambique will dramatically raise its spending to support displaced civilians in Cabo Delgado, from $75 million in 2020 to $129 million in 2021. The added funds are welcome, but still not reflective of the scale of the problem. The number of displaced civilians in Cabo Delgado has at least quintupled since this time last year. With the displacement has also come a huge disruption in the way government services are delivered, as Cabo Delgado provincial health director Magid Sabune admitted last week. Sabune has directed health workers not to demand ID cards before distributing HIV drugs and other treatments, and to give patients longer supplies of drugs, as it is unclear whether many displaced people will be able to receive care regularly going forward. So far, no government program has been undertaken to create new ID cards for people who lost theirs as they fled violence near their homes. As recently reported by Agência de Informação de Moçambique, the province has 164,240 HIV/AIDS patients, of whom 100,150 receive antiretrovirals, and 3,611 tuberculosis patients under treatment.

On the international level, Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi said on 18 November that Mozambique is open to receiving “any kind of support” for its counterinsurgency effort in Cabo Delgado. Nyusi did not elaborate on the particular types of support he is seeking, but specified that Mozambique is working “bilaterally” with countries from around the world to find assistance.

Meanwhile, Mirko Manzoni, the United Nations envoy charged with supporting the peace process between the Mozambican government and Renamo, urged direct donor support for the Mozambican military in an interview. Manzoni compared the Cabo Delgado insurgency to the Islamist insurgency in Mali in 2012, which precipitated an armed intervention by France. Manzoni was quick to caution that direct military intervention would “add fuel to the fire,” but he said that donors should not worry about “getting their hands dirty” by supporting the Mozambican counterinsurgency effort. Manzoni was presumably referring to widely reported human rights abuses by Mozambican forces — a record he is familiar with from his time focusing on the Renamo conflict.

Incident List

On 16 November 2020, FDS forces regained control of the village of Muidumbe (Muidumbe, Cabo Delgado), which had been under insurgent control since the end of October. Reports indicate that 16 insurgents died in the fighting. The group’s logistics were also destroyed.