In May 2020, Minneapolis police killed George Floyd, sparking a wave of protests across the United States. Building on initial research published in September 2020 in the wake of the first round of demonstrations, this report maps the protest movement through the beginning of 2021, examines how it has intersected with far-right extremism, and unpacks the aggressive government response in the year since Floyd’s death. All data are available for direct download here. Definitions and methodology decisions are explained in the US coverage FAQs and the US methodology brief. For more information, please check the full ACLED Resource Library.

Executive Summary

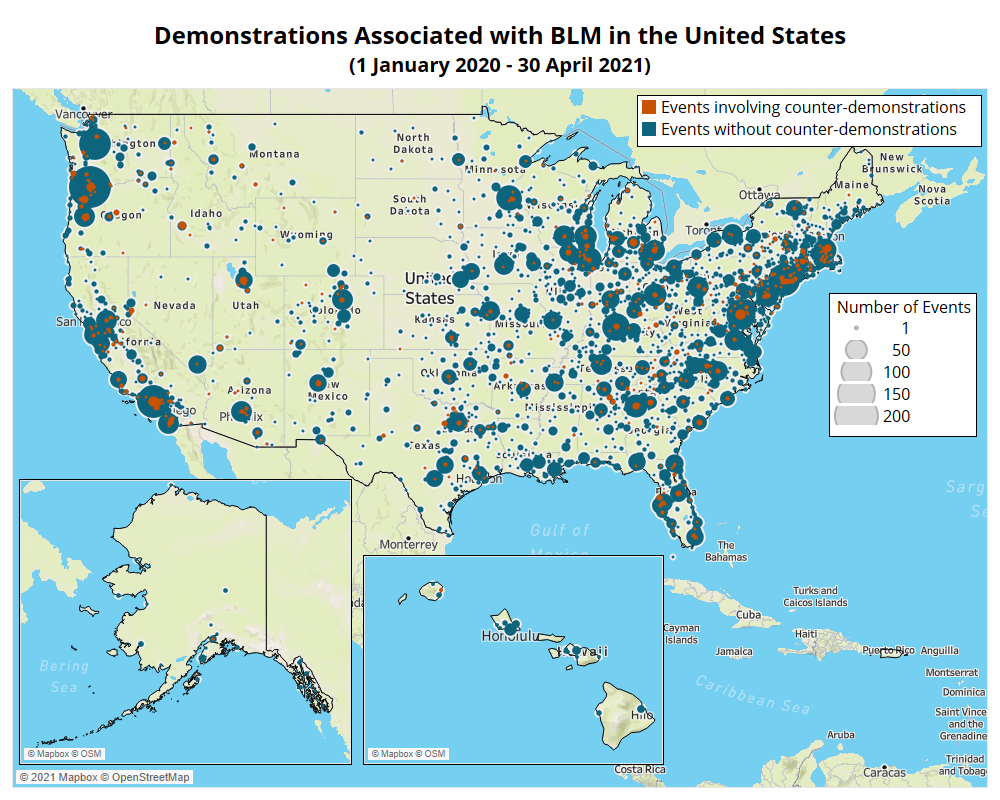

On 25 May 2020, Minneapolis police killed George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, sparking a massive wave of protests across the United States. According to new ACLED data, which are now updated from the start of last year to the present, more than 11,000 demonstrations associated with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement have been reported in nearly 3,000 distinct locations all around the country. While the vast majority have remained peaceful, they have faced violent intervention from the far right, as well as a disproportionately heavy-handed crackdown by law enforcement. Although demonstration rates have declined significantly since the heights of summer 2020, events have continued well into 2021, recently rising again around new cases of police brutality and the conviction of former police officer Derek Chauvin for Floyd’s murder. Opponents of the movement have seized the moment to introduce over 100 “anti-protest” bills in over 30 states, with new legislation increasing the penalties for protesting and even granting immunity for drivers who strike demonstrators with their vehicles.

Now with comprehensive data coverage of the past year of unrest, this report builds on initial research published in September 2020 in the wake of the first round of demonstrations. It maps the protest movement through the beginning of 2021, examines how it has intersected with far-right extremism, and unpacks the aggressive government response over the course of the year since Floyd’s death.

Key Findings

The BLM movement has remained overwhelmingly non-violent.

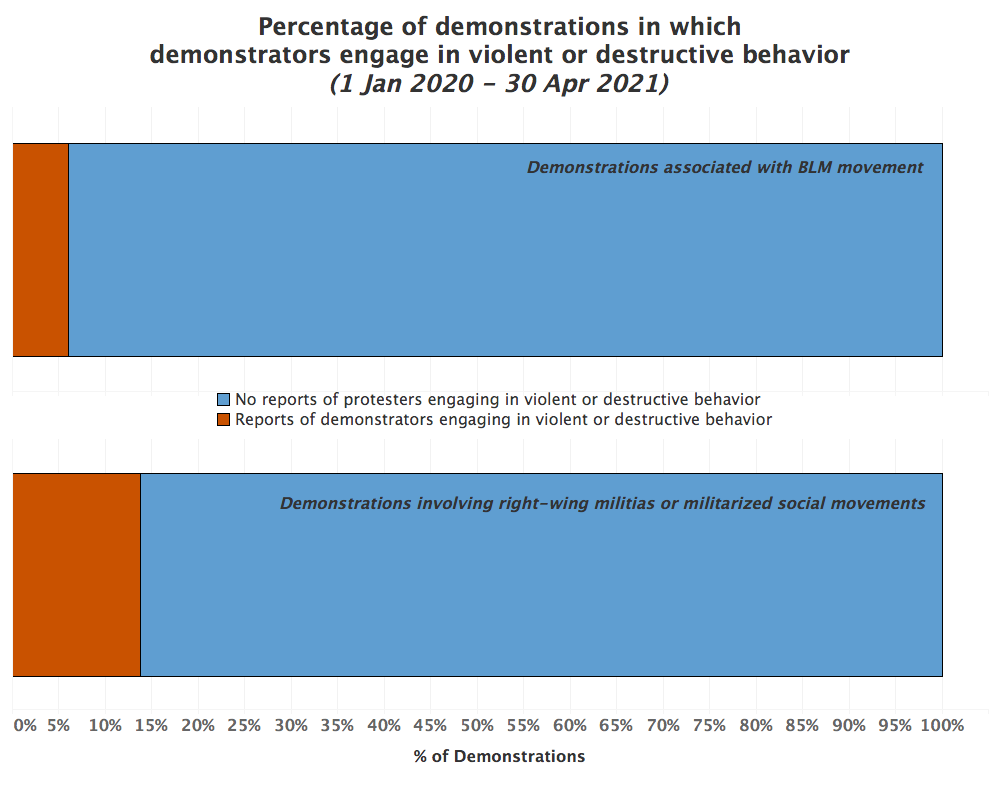

- Approximately 94% of all pro-BLM demonstrations have been peaceful, with 6% involving reports of violence, clashes with police, vandalism, looting, or other destructive activity.

- In the remaining 6%, it is not clear who instigated the violent or destructive activity. While some cases of violence or looting have been provoked by demonstrators, other events have escalated as a result of aggressive government action, intervention from right-wing groups or individual assailants, and car-ramming attacks.

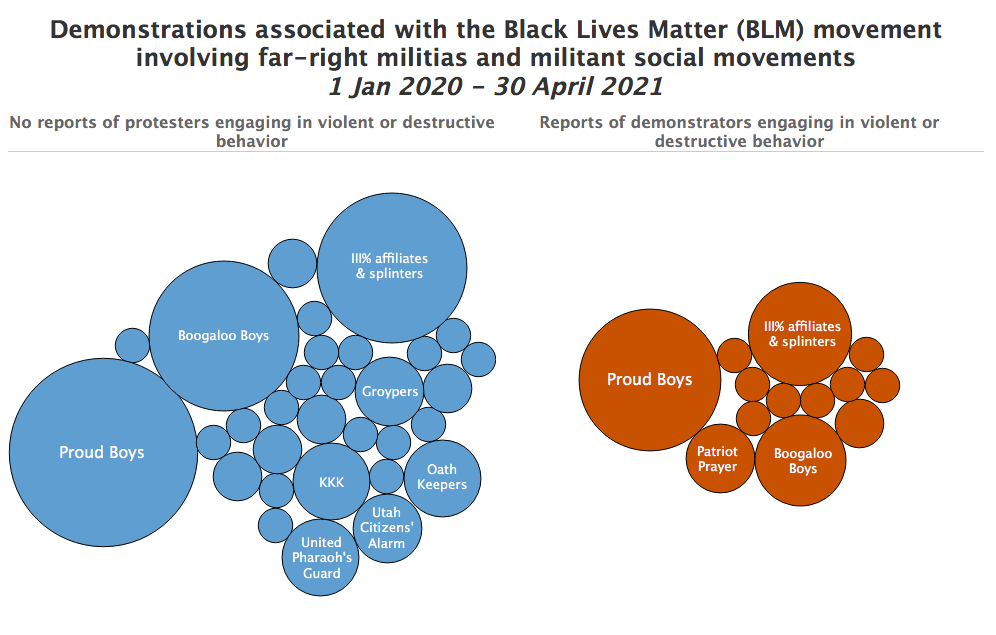

- In contrast, demonstrations involving right-wing militias or militant social movements have turned violent or destructive over twice as often, or nearly 14% of the time.

Police have taken a heavy-handed, militarized approach to the movement, escalating tensions.

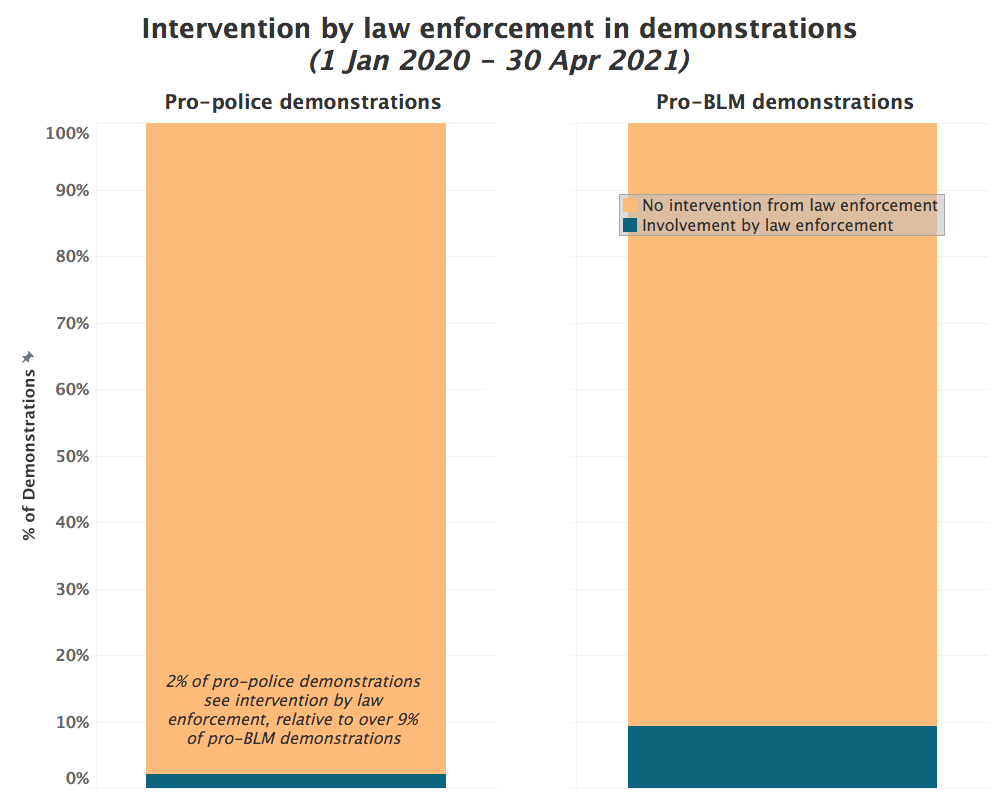

- Authorities are three times more likely to intervene in pro-BLM demonstrations than they are in other demonstrations.

- When intervening, they are more likely to use force against pro-BLM demonstrators: 52% of the time, compared to 26% of the time against all other demonstrators.

- These trends hold whether demonstrations have remained peaceful or not: authorities have engaged non-violent protests associated with BLM more than twice as often as other types of non-violent protests.

- When intervening, authorities have used force 37% of the time against peaceful pro-BLM protesters, compared to under 20% of the time against other peaceful protesters.

When right-wing militias and militant social movements engage with pro-BLM demonstrators, the risk of violence increases.

- At least 38 distinct, named far-right groups have engaged directly with pro-BLM demonstrators.

- Approximately 26% of these demonstrations have turned violent or destructive.

Pro-BLM protests have frequently involved counter-demonstrators, with over 750 counter-demonstrations nationwide.

- The ‘Back the Blue’ movement has played a key role in the right-wing response to BLM, organizing counter-demonstrations as well as holding independent rallies in support of the police.

- Nearly two-thirds of all ‘Back the Blue’ demonstrations are one-sided events, with no intervention by authorities. The lack of government engagement in pro-police demonstrations underlines a vast discrepancy in police response: 2% of pro-police demonstrations have been met with law enforcement intervention, relative to over 9% of pro-BLM demonstrations.

The BLM movement has also faced attacks by individual perpetrators, including a wave of car rammings targeting demonstrators.

- Car rammings are eight times more common at demonstrations associated with the BLM movement than at other types of demonstrations, with incidents reported at nearly 1% of all BLM-related events.

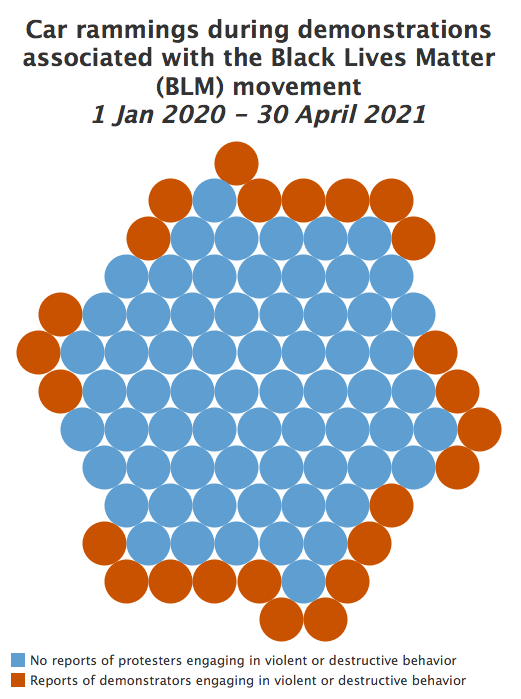

- The vast majority — 73% — of all BLM-related demonstrations that faced car-ramming attacks were peaceful.

Despite these trends, lawmakers in more than 30 states have introduced or enacted new “anti-protest” bills that restrict the right to free assembly or expand legal protections for drivers involved in car-ramming incidents.

- Although officials have cited instances of protest violence to justify this new legislative push, ACLED data show that, on average, the states pursuing these laws have the same rate of peaceful protests as states that have not pursued such legislation, meaning that violent demonstrations do not feature more prominently in the former than the latter.

- New legal cover for individuals involved in car-ramming incidents — which disproportionately take place at peaceful protests — raises the risk that attacks on non-violent demonstrators will only increase.

BLM-related demonstrations are beginning to resurge and expand geographically.

- In April 2021, over 500 pro-BLM demonstrations were reported around the country — more than in any month since September of last year.

- Even as 95% of all pro-BLM demonstrations since the start of this year have been non-violent, 41% of Americans remain opposed to the movement (Civiqs, 18 May 2021), meaning that disagreement and disinformation around its core goals will likely continue to fuel tension.

Introduction

On 25 May 2020, Minneapolis police killed George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, sparking a massive wave of protests across the United States. Demonstrations against police brutality and in support of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement quickly spread to every state in the country, with some estimates placing it among the largest mass mobilizations in American history (New York Times, 6 June 2020). In sheer number of events, it was undoubtedly the largest protest movement of 2020, leading the United States to register more demonstrations than any other country in the world.

A year since Floyd’s killing, how have the protests — and the backlash against the movement — evolved?

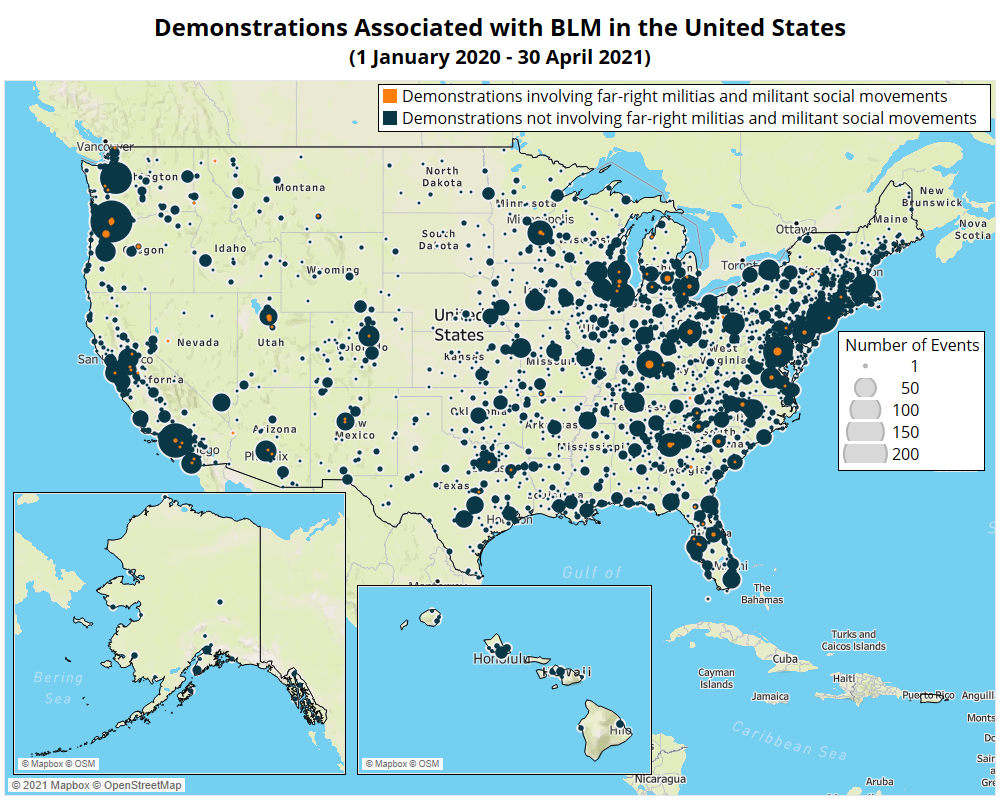

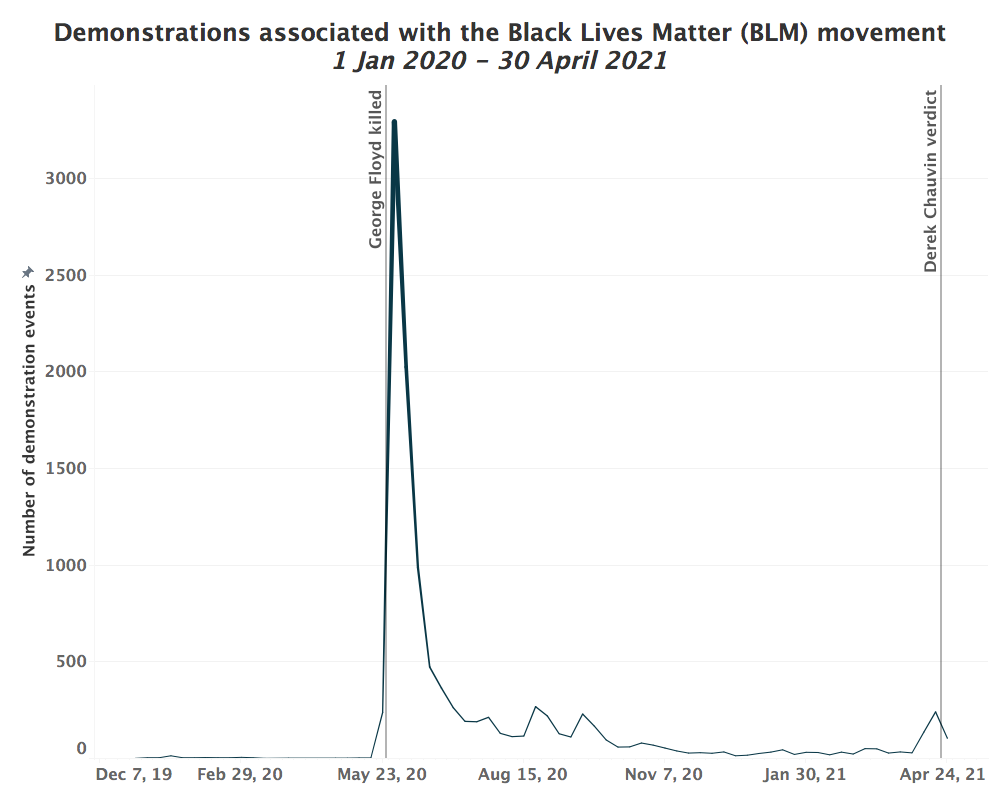

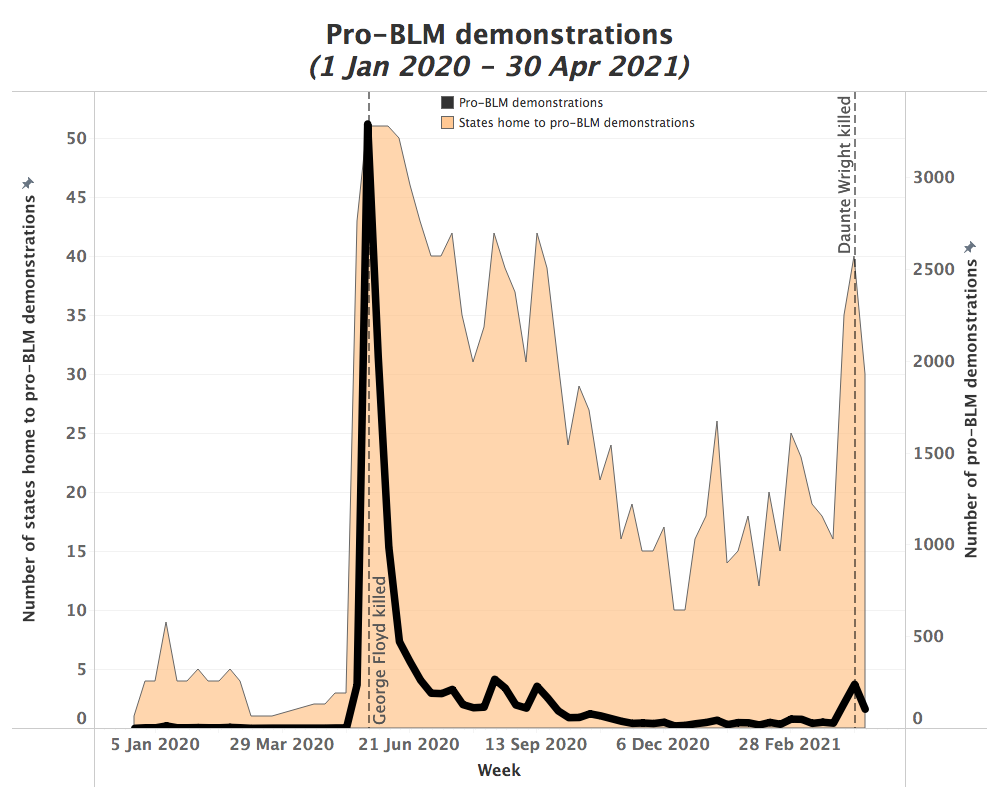

According to new ACLED data, which are now updated from the start of 2020 to the present,1ACLED data are collected in real time, updated weekly; this report analyzes data from January 2020 through April 2021. more than 11,000 demonstrations associated with the BLM movement have been reported in nearly 3,000 distinct locations all around the country. While the vast majority have remained peaceful, they have faced violent intervention from the far right, as well as a disproportionately heavy-handed crackdown by law enforcement. Although demonstration rates have declined significantly since the heights of summer 2020, events have continued well into 2021, recently rising again around new cases of police brutality and the conviction of former police officer Derek Chauvin for Floyd’s murder (see graph below). Opponents of the movement have seized the moment to introduce over 100 “anti-protest” bills in over 30 states, with new legislation increasing the penalties for protesting and even granting immunity for drivers who strike demonstrators with their vehicles (PEN America, 13 May 2021).

Now with comprehensive data coverage of the past year of unrest, this report builds on initial research published in September 2020 in the wake of the first round of demonstrations. It maps the protest movement through the beginning of 2021, examines how it has intersected with far-right extremism, and unpacks the aggressive government response over the course of the year since Floyd’s death.

ACLED coverage of the United States began in July 2020 as part of the US Crisis Monitor project, in partnership with the Bridging Divides Initiative at Princeton University.2 A report published in September 2020 initially explored trends in demonstration and political violence patterns during the summer of 2020, including demonstrations associated with the BLM movement. Over time, ACLED’s temporal coverage has expanded, allowing for deep dives into other trends: before the election, in October 2020, a joint report in partnership with MilitiaWatch explored the role of right-wing militia groups around the US election. In the aftermath of the election, a report examined the future of the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement as well as post-election trajectories for right-wing mobilization in the US. Earlier this year in March, a report explored the COVID-19 crisis and how it has exacerbated existing inequalities and political faultlines in the US, contributing to a surge of unrest throughout the country. Once a full year of coverage was achieved, US data were added to the main ACLED dataset, and the project came to a close. Real-time coverage of the US continues as part of ACLED’s standard data collection program with publicly accessible data published weekly.3Visit ACLED’s US Research Hub to access the full dataset, additional reports and analysis, methodology resources, and an interactive dashboard mapping the latest data.

Demonstrations and Disinformation

ACLED data show that the overwhelming majority of demonstrations associated with the BLM movement have been peaceful. Approximately 94% of all pro-BLM demonstrations have been non-violent, with 6% involving reports of violence, clashes with police, vandalism, looting, or other destructive activity. Of that remaining 6%, it is not clear who instigated the violent or destructive activity.4ACLED aims to code the most objective aspects of conflict and protest reporting, while limiting the more subjective aspects. The latter aspects — such as ‘who threw the first punch,’ for example — can be the most biased components of reporting. Limiting to the objective aspects — e.g. what occurred, who was there, where did it occur, when did it occur, was there any report of violence or destructive activity — allows for greater reliability of the data. This means, however, that it is not possible to determine who initiated the violence or destructive activity that might have happened at a demonstration using the variables that ACLED codes. When this information is available, it is included in the ‘Notes’ column of events. Users can review the ‘Notes’ to parse out such distinctions in certain events, but should remain cognizant of the fact that reporting on this point is often incomplete, and aware of possible bias in such reporting when included given its subjective nature. While some cases of violence or looting have been provoked by demonstrators, other events have escalated as a result of aggressive police action, intervention from right-wing armed groups, and individual car-ramming attacks (see next section). In contrast to the BLM movement, demonstrations involving right-wing militias or militant social movements (MSMs) — such as the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, or the Three Percenters, among others — have turned violent or destructive over twice as often, or nearly 14% of the time (see graph below).

Initial surveys of American adults pointed to widespread support for the BLM movement across racial and political lines. According to a Pew survey, 67% of all adults — including 60% of white Americans, 86% of Black Americans, and 40% of Republicans — surveyed between 4 June and 10 June 2020, during the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s killing, supported the movement (Pew Research, 12 June 2020). Yet public approval waned over the ensuing months. By September 2020, support dropped to 55% of all adults, with less than half of white Americans and 19% of Republicans supporting the movement. Only among Black Americans did support increase, by 1% (Pew Research, 16 September 2020).

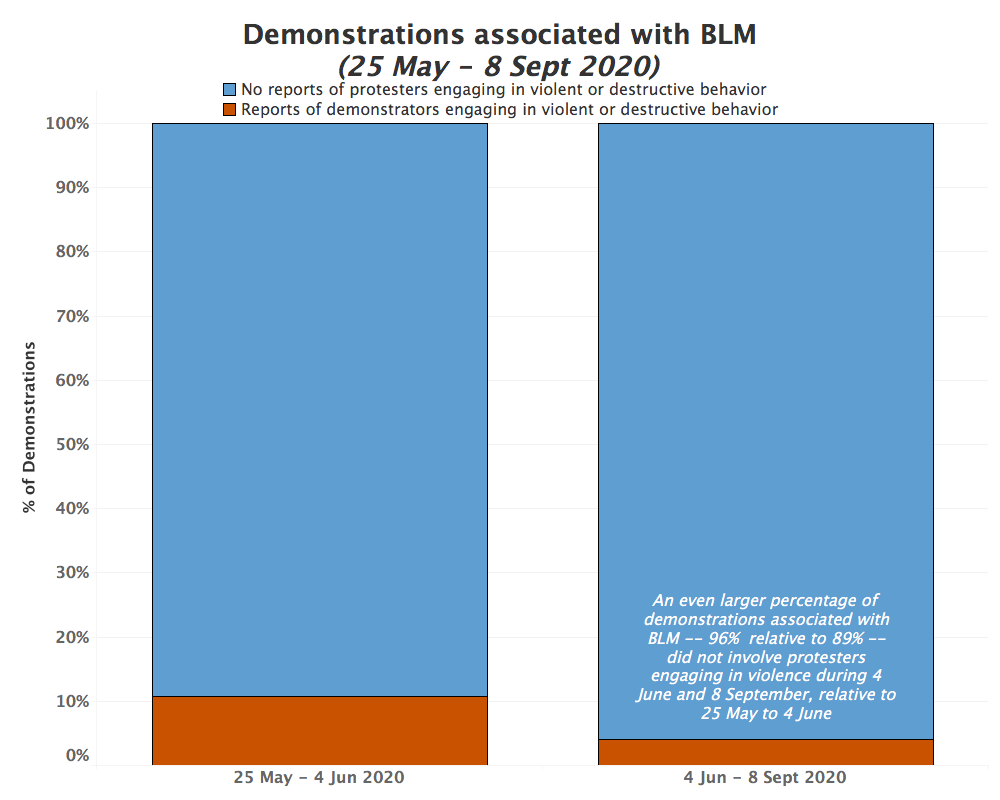

Reports indicate that the decline in support, especially among Republicans, was linked to a right-wing campaign to amplify destructive behavior on the fringes of demonstrations associated with the movement, and to paint BLM-related activity as centrally organized, violent, and dangerous (Intercept, 13 May 2021). This campaign appeared to have a clear effect on public opinion: the perception that the movement was predominantly destructive actually increased despite the proportion of demonstrations involving violent activity decreasing since the initial burst of unrest immediately following Floyd’s killing. From 25 May to 4 June 2020, when the first Pew survey was conducted, ACLED data show that 89% of all demonstrations associated with BLM had been non-violent. However, between 4 June and 8 September 2020, when the second Pew survey was conducted and found a significant drop in support, ACLED data show that more than 96% of all demonstrations associated with the movement were non-violent (see graph below). In short, support for the movement declined considerably despite a significant increase in the proportion of peaceful events.

The push to portray the demonstrations as inherently violent and more dangerous than other social movements became a defining position for the Republican Party and a major talking point in the reelection campaign of then-President Donald Trump. Although the US Office of Special Counsel determined the BLM movement was apolitical in July 2020 (USA Today, 17 July 2020), the BLM movement nevertheless became a highly contentious and partisan issue. In late June 2020, Trump accused a New York-based BLM activist of “Treason, Sedition, Insurrection!” on Twitter (Washington Post, 25 June 2020). By the beginning of July 2020, Trump began referring to the BLM movement as a “symbol of hate” (BBC, 2 July 2020). He later tweeted violent videos inaccurately or misleadingly attributing blame to BLM and intentionally conflating the movement with anarchists and ‘Antifa’ (Washington Post, 1 September 2020). By August 2020, the BLM movement was a primary topic at the Republican National Convention. Mark and Patricia McCloskey, a St. Louis couple who gained both notoriety and felony charges for brandishing weapons at peaceful pro-BLM demonstrators, spoke about “fearing death” during the protest and alleged that the demonstrators “are not satisfied spreading chaos and violence into our cities” (Youtube, 24 August 2020; Washington Post, 25 August 2020). When speaking at the convention two days later, Trump’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani portrayed the BLM movement as a violent menace to the safety of all Americans, especially those in the suburbs, and called the election a choice between law and order and mayhem (LA Times, 27 August 2020). In the months preceding the 2020 presidential election, Trump defended Kyle Rittenhouse, a minor who was illegally armed and killed two pro-BLM demonstrators in Kenosha, Wisconsin (CNN, 27 August 2020; USA Today, 31 August 2020). More recently, in May 2021, Mark McCloskey announced a Senate run in Missouri, campaigning on a platform that promises to defend America against “the mob” that is BLM (NBC News, 18 May 2021).

A Heavy-handed Response

These misleading narratives — perpetuated by the Trump administration and other Republican elites — shaped not only public opinion, but also the response to the movement from both law enforcement and non-state groups alike. Demonstrations associated with BLM have frequently been met with aggressive intervention from a range of actors, including federal authorities and local police as well as far-right militias, counter-demonstrators, and individual attackers.

Government Authorities

Engagement and Force

In the aftermath of Floyd’s killing, then-President Trump quickly called for a violent government response to suppress the demonstrations, urging authorities to use lethal force if demonstrators engaged in looting (New York Magazine, 1 June 2020) and instructing governors to “cut through [protesters] like butter” (Vox, 2 June 2020). Then-Defense Secretary Mark Esper, in remarks he later recanted, identified domestic protest sites as a “battlespace” that law enforcement and National Guard needed to “dominate” and then-Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy declared that the protest response mission was “D-Day for the National Guard” (Military Times, 1 June 2020; Washington Post, 15 April 2021).

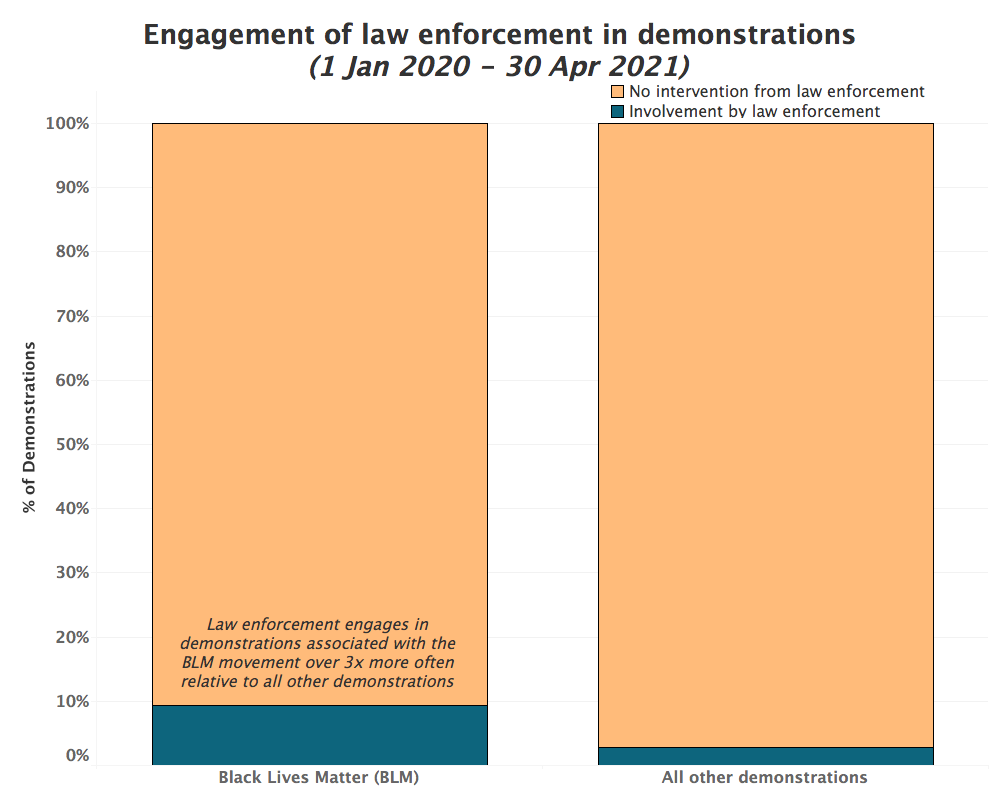

Many federal and local law enforcement agencies heeded these directives. Government authorities — including police as well as federal agents and military forces, like the National Guard — have engaged in demonstrations associated with the BLM movement three times more often than they have engaged in any other type of demonstration in the country (see graph below), according to ACLED data. Authorities have intervened in BLM-related demonstrations over 9% of the time, compared to under 3% of the time for all other demonstrations.

This trend is not a function of BLM-related demonstrations being more violent or destructive than other demonstrations: authorities are more likely to intervene in demonstrations associated with the BLM movement whether they are peaceful or not. Even when examining only protests that did not involve violence, vandalism, looting, or other destructive activity, law enforcement have still engaged in peaceful BLM-related demonstrations over twice as often: 5% of the time compared to 2% of the time for other types of peaceful protests. This trend suggests that law enforcement responses are not simply dictated by situational threats, but are rather guided by strategic approaches to policing certain demonstrations, divorced from the actual actions of demonstrators.

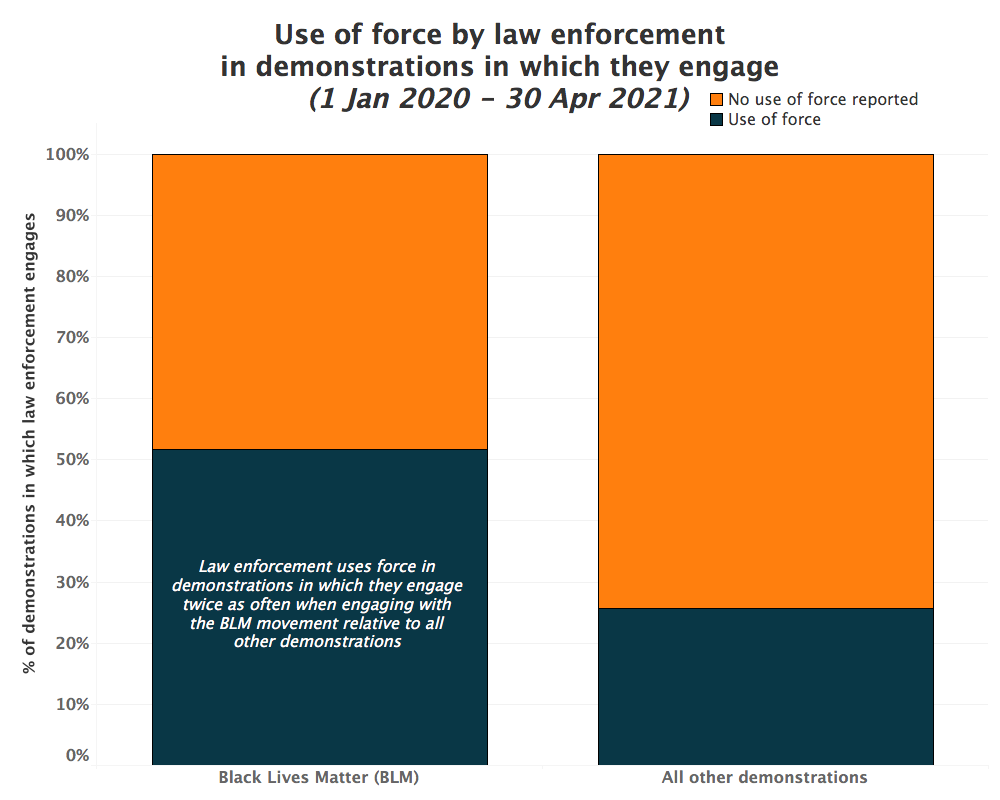

When authorities do intervene in demonstrations, they have used force — such as firing less-lethal weapons like tear gas, rubber bullets, and pepper spray or beating demonstrators with batons — more often when engaging with demonstrators associated with the BLM movement: over half — 52% — the time, compared to approximately a quarter — 26% — of the time for all other demonstrations (see graph below).

Again, the data suggest that the decision to use force is not linked solely to demonstrator behavior. Overall, authorities are more than four times as likely to use force against peaceful pro-BLM protests than they are against other types of peaceful protests. In peaceful protests where they have decided to intervene, authorities have used force over a third — 37% — of the time against pro-BLM protesters, compared to under 20% of the time against other protesters. For example, on 1 June 2020, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, police fired teargas, pepper spray, and less-lethal munitions at peaceful marchers they corralled into a highway embankment. Videos surfaced following the protest showing a police officer pepper-spraying kneeling demonstrators directly in the face. The officer has since been fired, and police and city leaders later described the response as “unjustified” and apologized for early statements accusing the demonstrators of engaging in violent activity (New York Times, 25 June 2020; Fox29 22 July 2020; Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 June 2020). In Washington, DC that same day, an array of local and federal authorities used smoke canisters and pepper balls against a peaceful pro-BLM protest in Lafayette Square across from the White House in order to clear a path for then-President Trump to take a photo at nearby St. John’s Church (Washington Post, 2 June 2020; Amnesty International, 4 August 2021). Reports have since emerged that a police officer used a shield and then his hand to hit two Australian journalists before also using smoke canisters, stinger balls, and pepper balls against them (US Press Freedom Tracker, 29 October 2020; ProPublica 14 December 2020). The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found that police did not allow the demonstrators to return home, instead kettling them and conducting mass arrests while using “excessive force” (ACLU, 10 March 2021). All 300 arrested were cited for curfew violations (Washington Post, 10 March 2021).

The widespread use of force against the BLM movement comes amid the broader militarization of American police agencies, a trend that is itself linked to higher rates of police violence (Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 8 October 2020). Throughout the country, law enforcement agents, sometimes without insignia, engaged with pro-BLM demonstrators while armed with military weaponry and equipment, including Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) armored vehicles designed for survivability in conflict zones (Amnesty International, 4 August 2020). In Los Angeles, California, police used rounds launched from military style grenade launchers, shotguns, and assault rifles on pro-BLM demonstrators liberally and to dangerous effect — at least 12 people were shot in the head by kinetic impact projectiles on 29 May 2020 alone, suffering serious injuries (Physicians for Human Rights, 14 September 2020). Overall, Los Angeles law enforcement agencies reported that nearly 10,000 rounds of 37mm and 40mm less-lethal munitions were not returned to storehouses during the period of 29 May to 2 June 2020, implying they were fired at demonstrators (Los Angeles City Clerk, 10 March 2021).

The aggressive, militarized response to the demonstrations has in many cases only exacerbated tensions between protesters and law enforcement. For example, the deployment of federal agents in Oregon last summer, including the Protecting American Communities Task Force (PACT), coupled with their more aggressive tactics — including frequent use excessive force and arbitrary detention of suspected protesters in unmarked vehicles (Oregon Live, 16 July 2020; USA Today, 4 August 2020) — appears to have escalated unrest in the state. Between the end of May and the deployment of the PACT at the start of July, approximately 16% of all demonstrations associated with BLM in Oregon were met with government intervention, and authorities used force against demonstrators at a relatively low rate. During the following month, however, authorities intervened in nearly 51% of demonstrations, with 70% of those involving use of force by government personnel. Prior to the PACT deployment, 87% of demonstrations in Oregon were non-violent, while post-deployment, the percentage of violent demonstrations rose from 13% to over 36%, suggesting that the federal response only raised tensions and aggravated unrest.

The heavy-handed police response has often escalated protest situations in other states as well, prompting clashes with demonstrators and raising the risk of violence.5ACLED aims to code the most objective aspects of conflict and protest reporting, while limiting the more subjective aspects. The latter aspects — such as ‘who threw the first punch,’ for example — can be the most biased components of reporting. Limiting to the objective aspects — e.g. what occurred, who was there, where did it occur, when did it occur, was there any report of violence or destructive activity — allows for greater reliability of the data. This means, however, that it is not possible to determine who initiated the violence or destructive activity that might have happened at a demonstration using the variables that ACLED codes. When this information is available, it is included in the ‘Notes’ column of events. Users can review the ‘Notes’ to parse out such distinctions in certain events, but should remain cognizant of the fact that reporting on this point is often incomplete, and aware of possible bias in such reporting when included given its subjective nature. Reviews of police departments in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Indianapolis, Indiana found that the police approach to pro-BLM demonstrations inflamed rather than defused tensions (New York Times, 20 March 2021). For instance, thousands of people protested peacefully for multiple hours on 29 May in Indianapolis before police in riot gear attempted to disperse demonstrators, after which the demonstrations devolved into riots that lasted throughout the evening (WBOI, 29 May 2020; South Bend Tribune, 31 May 2020; New York Times, 20 March 2021).

These trends also seem to hold elsewhere in the US. On 29 May 2020, thousands of BLM supporters demonstrated in Omaha, Nebraska. The protest was initially peaceful, but became violent after police deployed across the street from demonstrators in riot gear and what appeared to be an MRAP vehicle (Twitter @EmilyTencerKETV, 30 May 2020). Police soon deployed tear gas, pepper balls, and flash-bang grenades against demonstrators, who claimed they were provoked into violence by indiscriminate use of police force (KETV Channel 7, 8 June 2020). One demonstrator described the incident as, “a peaceful protest against police brutality [that] was met with police brutality” (Omaha World Herald, 27 April 2021).

The Strategic Response Group (SRG) — a specialized “anti-terror” police unit in New York also designed to respond to instances of public disorder — has engaged demonstrators in numerous instances, often as the instigating party, earning it the nickname “goon squad” among activists (Gothamist, 17 December 2015; Intercept, 7 April 2021). Human Rights Watch described an interaction between peaceful pro-BLM demonstrators and the SRG in the Bronx, New York on 4 June 2020 as a “planned assault” in which more than 250 people were arrested and at least 61 demonstrators suffered injuries, ranging from broken bones to nerve damage (Human Rights Watch, 30 September 2020). In this instance, protesters remained peaceful despite the extreme level of violence inflicted on them. A few days prior, on 30 May 2020, SRG and regular police officers had also engaged in numerous instances of violence against peaceful protesters in support of the BLM movement in Brooklyn, New York. An officer from the SRG reportedly pulled down a demonstrator’s mask in order to pepper spray him in the face to greater effect, while two NYPD vehicles rammed demonstrators in the street (Department of Investigation – New York City, December 2020; NPR, 14 January 2021; Intercept, 7 April 2021). Contrary to the events in the Bronx on 4 June, demonstrations in Brooklyn descended into violence in the face of excessive police force on 30 May, underlining how extreme policing has served to exacerbate tensions. Internal documents indicate that most New York police officers “at the George Floyd protests received only vague academy training that emphasized arresting protesters over defending their rights,” encouraging authorities to take a confrontational approach to even peaceful and law-abiding demonstrators (Intercept, 5 May 2021).

Civilians outside of protests have also been impacted: in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a video posted on Twitter shows the Minnesota National Guard and Minneapolis police sweeping a residential street in the city, yelling “Light ‘em up!” while firing paint rounds at a resident on their front porch after they did not follow orders to return inside (CBS Minnesota, 30 May 2020).

Arrests

Authorities have also targeted BLM demonstrators and activists for arrest. From 29 May to 2 June 2020, the Los Angeles Police Department arrested at least 4,029 individuals (Los Angeles City Clerk, 10 March 2021), with only 3-5% arrested for looting. The vast majority were arrested for curfew violations and failure to obey a dispersal order (Los Angeles Times, 6 June 2020). By 4 June, the number of arrests across the country had reached at least 10,000 people, with New York, Dallas, and Philadelphia following Los Angeles in total arrests (AP, 4 June 2020). At least 129 journalists were arrested while covering demonstrations associated with the BLM movement in 2020, accounting for 93% of all journalist arrests during demonstrations during the year (Reporter’s Committee, 3 May 2021).

Police have routinely used a strategy to “trap and detain” demonstrators — also known as “kettling” — by forcing them into an area without escape routes before conducting mass arrests (USA Today, 24 June 2020). The use of the tactic by police has been widespread, with kettling tactics reported from coastal cities, such as Los Angeles and New York, to central cities like Des Moines, Iowa and Omaha, Nebraska (ABC7 Los Angeles, 4 February 2021; New York Times, 4 November 2020; USA Today, 23 June 2020; Yahoo! News, 29 July 2020). The use of “kettling” tactics on largely peaceful demonstrators has raised concerns that the purpose of the arrests is to stifle dissent and to make demonstrations appear more violent by provoking confrontations with demonstrators leading to significantly higher arrest numbers as part of a public relations strategy (Independent, 17 January 2021; Metro Times, 7 October 2020).

The mass arrests of demonstrators associated with the BLM movement contrast starkly with the dearth of arrests made during right-wing demonstrations at capitol buildings across the country. Police in Washington, DC arrested more than five times the number of pro-BLM demonstrators on 1 June 2020 than pro-Trump demonstrators during the storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 (CNN, 8 January 2021). The trend was even more pronounced locally in 2020 and 2021: right-wing demonstrators trespassed into the grounds of governor residences and state capitol buildings in Kansas, Michigan, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Washington with fewer than a dozen arrests in total (NBC News, 6 January 2021; BBC, 30 May 2020; Fox News, 22 April 2020; Deadline, 20 December 2020; Seattle Times, 6 January 2021).

A wave of new “anti-protest” legislation around the country threatens to increase restrictions on demonstration activity and expand police discretion to arrest demonstrators (Al Jazeera, 22 April 2021).

“Anti-protest” Legislation

Since June 2020, state officials have introduced at least 100 proposals that would restrict the right to free assembly (PEN America, 13 May 2021). Republican lawmakers have proposed 81 bills in over 30 states during the 2021 legislative session alone, more than double the number introduced in any other year, according to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (New York Times, 21 April 2021; International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, 22 April 2021). These bills have become law in states like Oklahoma and Florida, with new legislation increasing the penalties for “unlawful protesting” and “granting immunity to drivers whose vehicles strike and injure protesters in public streets” (New York Times, 21 April 2021).

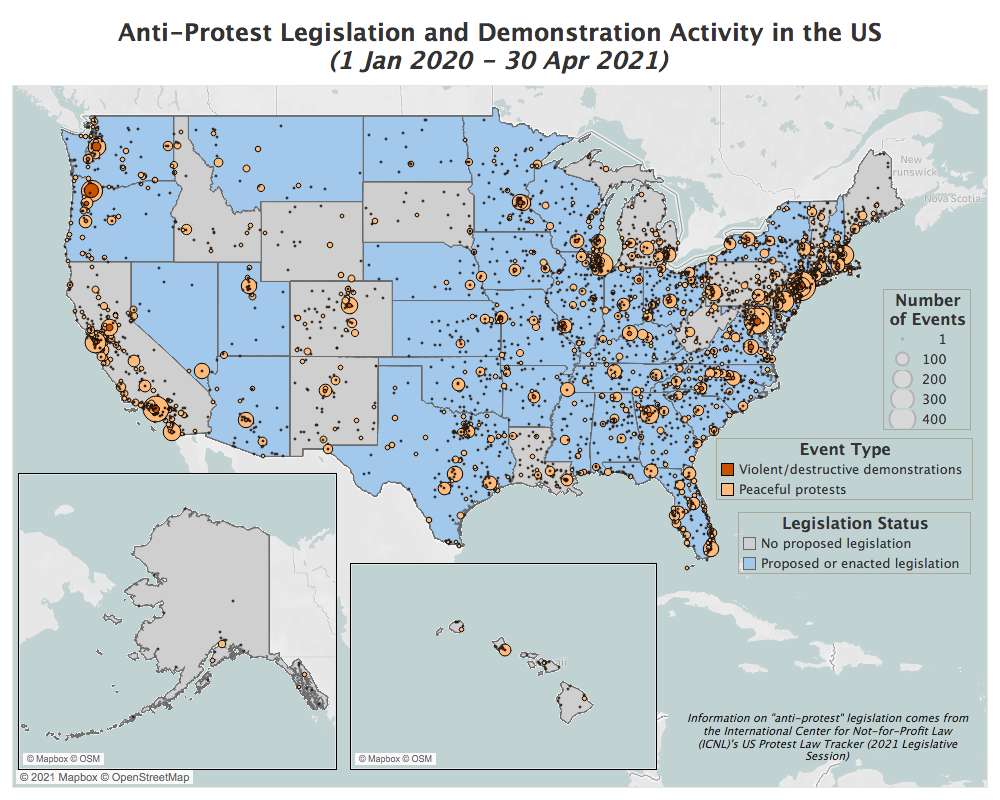

Although officials have cited instances of protest violence over the past year to justify this new legislative push — with Governor Ron DeSantis labelling Florida’s law “the strongest anti-looting, anti-rioting, pro-law-enforcement piece of legislation in the country” (New York Times, 21 April 2021) — most of these states have experienced low levels of violent or destructive demonstration activity (see map below). ACLED data show that, on average, the states in which strict “anti-protest” laws have been proposed have the same rate of peaceful protests as states that have not pursued such legislation, meaning that violent demonstrations do not feature more prominently in the former than the latter. States like Florida and Oklahoma, which have promulgated some of the most restrictive new laws, have actually seen a lower proportion of demonstrations involving violent or destructive activity than most other states in the country.

The states considering new laws have been home, however, to a higher proportion of demonstrations associated with the BLM movement compared to other states. In the 34 states that have introduced or enacted “anti-protest” bills during the 2021 legislative session (New York Times, 21 April 2021; International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, 22 April 2021), 43% of all demonstrations recorded since the start of last year have been related to the BLM movement. In the 16 states that have not introduced new legislation, only 37% of all demonstrations have been associated with BLM.

Police have also taken a more heavy-handed approach to protests in these 34 states: since the start of last year, authorities have engaged in at least 6% of all demonstrations in the states that have pursued new laws, relative to 5% in other states, and they have used force in 3%, compared to 2% in other states. Civil rights advocates argue that “laws are already in the books to stave off riots” (Business Insider, 21 April 2021), and the higher rates of police intervention and force in these states, despite equal levels of peaceful demonstration activity when compared to the rest of the country, suggest that authorities are already aggressively enforcing existing legislation. These trends have raised concerns among activists that the true purpose of this new legislative push is to “silence dissent” and foster “a culture of impunity among protest opponents” (ACLU, 19 April 2021; Intercept, 21 January 2021).

While some of these bills have been introduced in reaction to the Capitol riot in January 2021, the disparity in the police response to BLM-linked protests compared to right-wing protests demonstrated by ACLED research provides “reason to anticipate that even bills introduced on the pretext of responding to a right-wing insurrection are likely to be disproportionately enforced against movements led by people of color or focused on issues of racial and social justice” (PEN America, 13 May 2021). Citing analysis of ACLED data, PEN America has cautioned that “the bills often use vague terminology for concepts like ‘unlawful assembly,’ which would afford police wide discretion to determine what constitutes criminal activity — discretion that evidence shows is likely to be wielded in biased or arbitrary ways” (PEN America, 13 May 2021).

The Far-right

The right-wing response — from militias and street-fighting organizations to armed individuals and car-ramming attacks — has primarily focused on direct opposition to the goals and operations of BLM-affiliated activists and supporters.

Right-wing Counter-demonstrators

Counter-demonstrations against BLM-related events have been a major feature of the American protest environment. ACLED records over 750 counter-demonstrations against BLM nationwide between the start of last year and April 2021.

Far-right Militias and Militant Social Movements

Militia groups and MSMs specifically have been active at over 12% — more than 90 — of these BLM-linked demonstrations, almost always in direct opposition to pro-BLM actors. Approximately a third — 29% — of all demonstrations involving right-wing militias or MSMs since the start of last year have been associated with the BLM movement — a particularly significant percentage in a year with high levels of mobilization around right-wing causes, including opposition to COVID-19 restrictions, the Trump re-election campaign, and the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement in the aftermath of the election.

Right-wing militia and MSM engagement with BLM-associated demonstrations varies by organization, with different levels of opposition. At least 38 distinct, named far-right militias and MSMs have engaged directly in demonstrations associated with BLM. When these groups have engaged, the demonstrations have been violent or destructive over a quarter — 26% — of the time. The figure below depicts the rate of involvement of various named far-right militias and MSMs in demonstrations associated with BLM.

As seen in the figure, Proud Boys involvement has been the most common. They have engaged directly in nearly 50 demonstrations in which they were counter to BLM-supporters, or nearly a third — 28% — of all BLM-related demonstrations in which named militia groups or MSMs also engaged. In over a third — 36% — of such demonstrations involving Proud Boys, the events became violent or destructive (for more on the Proud Boys, see this ACLED actor profile.)

The III% movement is extremely devolved and provides an aesthetic brand for far-right armed organizing, which has often included directly responding to BLM-associated demonstrations. The organization has historically claimed to oppose the ‘tyranny’ of the American security state, but its members have often acted as defenders of the police against calls from BLM-related demonstrations. III%-branded actors have engaged in approximately 17% of the demonstrations that involved both pro-BLM actors and militia groups. Demonstrations involving III% affiliates and pro-BLM demonstrators have turned violent nearly a third of the time since the start of last year, and have taken place across four states and Washington, DC. While the III% pattern of behavior bears some similarities to the Proud Boys when engaging with pro-BLM actors — such as a similar rate of involvement in violent demonstrations — the III% brand differs from the Proud Boys in that it was not founded in direct opposition to BLM actors and precedes Trump. In almost half of events involving pro-BLM demonstrators in which III% affiliates have engaged, the Proud Boys were also involved, showing not only a strategic alignment but also coordination in physical response.

The Boogaloo Boys present a unique case when it comes to interaction with the BLM movement, as they have responded to BLM-related demonstrations with various types of engagement and strategies. Boogaloo Boys account for 16% of demonstrations associated with BLM in which named militia groups or MSMs also engaged. In 60% of demonstrations associated with the BLM movement in which Boogaloo adherents actively engaged, they showed up in direct opposition to BLM supporters — and in just over 10% of these, there is evidence that Boogaloo adherents were in attendance specifically as ‘agents provocateurs.’ And yet, in the other 40% of demonstrations associated with the BLM movement in which Boogaloo adherents actively engaged, the Boogaloo Boys provided support or expressed solidarity with BLM activists. However, this support has not always been well-received. For example, last month, Boogaloo members attempted to join a BLM-affiliated demonstration in Lansing, Michigan against the police killing of Anthony Hulon, a white man, but the Boogaloo members were told by the event organizers that they were not welcome at the protest — resulting in them instead standing across the street from the demonstration (News2Share, 2 April 2021; MLive 5 April 2021).

It is important to note that the Boogaloo ‘movement’ has no central structure, and has many levels of discourse and disagreement among adherents. The central ideological line for the Boogaloo, and from which the ‘movement’ draws its name, is the notion of escalating the political situation towards civil war (e.g. “The Boogaloo”). In some cases, Boogaloo cells have made the cynical calculation that BLM-associated protests as part of the George Floyd uprisings were the most accessible and useful means through which the Boogaloo could escalate towards open conflict. While some adherents may genuinely believe in the principles of the BLM movement, there is already substantial evidence that many others do not share these beliefs in private (Bellingcat, 27 May 2020; Twitter @TwilightZoneAFA, 30 September 2020).

An example of an explicitly pro-BLM Boogaloo cell can be found in the Kentucky-based United Pharaoh’s Guard (UPG), also briefly known as the “Louijihadeen” (Youtube, 27 August 2020). Two UPG Boogaloo adherents were arrested by federal officers for their alleged involvement in inciting riots on 6 January 2021 in downtown Louisville while ‘protecting’ pro-BLM demonstrators (Courier Journal, 11 February 2021). Investigators claim that, after setting up a barricade in the city, one of the two opened fire at a vehicle before fleeing (WDRB, 11 February 2021). However, like the Boogaloo ‘movement’ more largely, their beliefs remain nebulous; despite their pro-BLM and anti-police stance, the group has also coordinated with a III% militia leader to patrol downtown Louisville on Election Day, for example (News2Share, 3 November 2020)

Pro-police Advocates

A crucial component of the right-wing response to BLM-associated demonstrations is mobilization around defending the police. This is in large part due to the BLM movement’s direct activism against police brutality and, more specifically, the burgeoning calls to ‘defund the police’ since the killing of George Floyd. The pro-police response has evolved from previous ‘Blue Lives Matter’ campaigns to engaging with a number of movements and organizations, including representatives from the Proud Boys, Republican-elected officials, III% militia groups, and QAnon, among others. More than 270 demonstration events have taken place with opposing sides including pro-BLM actors facing off against pro-police actors between the start of last year and the end of April 2021, spanning 42 states.

Within the world of anti-BLM and pro-police organizing, ‘Back the Blue’ (BTB) is a key national movement. BTB was created in defense of the police by ACT for America, a Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC)-designated hate group. ACT for America was founded as an anti-Muslim organization and was highly involved in the ‘March Against Shariah’ rallies in 2017 (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2021). While the origins of BTB as a movement cannot be ignored, BTB has become more decentralized from the ACT for America umbrella, and has come to take on different local characteristics depending on what shape pro-police and anti-BLM activism takes in context. Some local organizers have even come forward to disavow ACT for America, claiming to be fully independent from the designated hate group (Patch, 9 September 2020). Meanwhile, other events have still been explicitly endorsed or organized by ACT for America since the 2017 rallies (Southern Poverty Law Center, 28 August 2018). The raison d’etre for BTB as a movement is to counter BLM-associated activism. It is therefore not surprising that the group has been involved in over 110 counter-demonstrations against BLM-related events across 29 states since the start of last year.

BTB-associated demonstrators are not always positioned solely in opposition to BLM. Pro-police demonstrations are often organized as one-sided demonstrations to express support and admiration for the police — meaning they not only do not engage directly with pro-BLM demonstrators, but they also do not engage with law enforcement. Nearly two-thirds of all BTB demonstrations are one-sided events, with no intervention by authorities. The lack of government engagement in pro-police demonstrations underlines a vast discrepancy in police responses to demonstrations: 2% of pro-police demonstrations have been met with intervention from law enforcement since the start of last year, relative to over 9% of demonstrations associated with the BLM movement (see graph below).

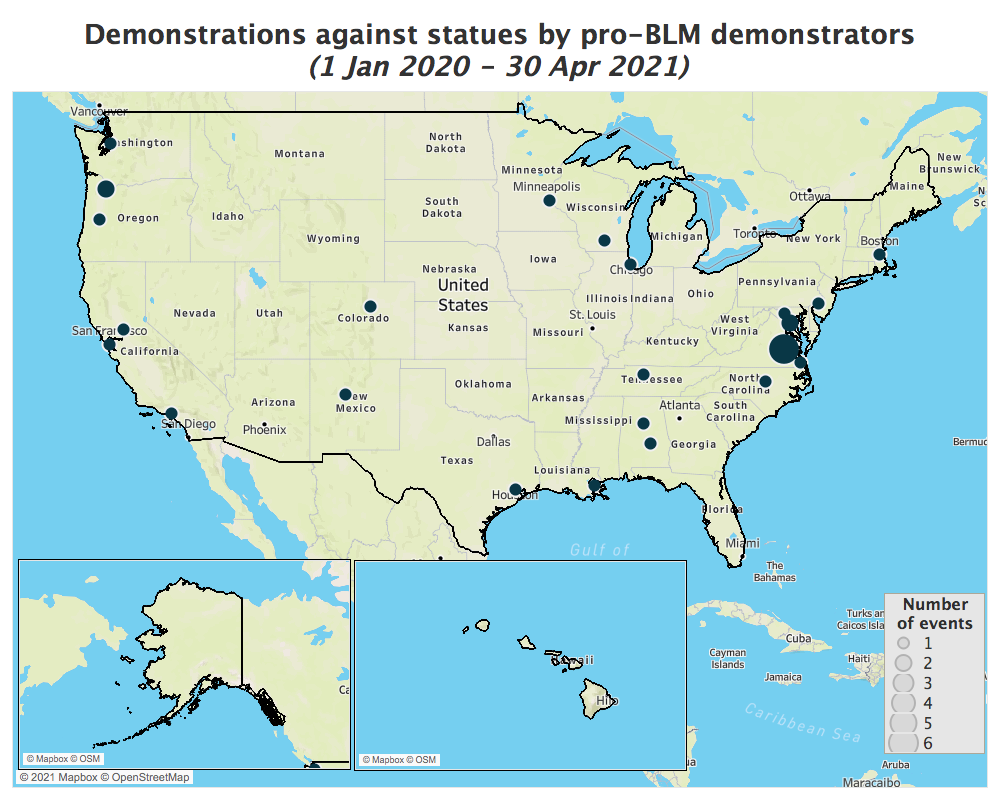

Protection of Statues

One of the major targets of BLM activism at the local level has been statues linked to white supremacy or America’s legacy of racism (New York Times, 3 June 2020). Demonstrations against Confederate monuments or statues of Christopher Columbus encouraged the passage of local legislation to take down the displays in towns around the country, resulting in the removal of approximately 100 such monuments (NPR, 23 February 2021; CBS News, 25 September 2020). In some cases, statues were damaged or destroyed by demonstrators. But in many cases, BLM-associated demonstrators were preempted by right-wing actors seeking to protect or preserve these monuments. Legal challenges have been impossible in some areas, leading to direct confrontation in the street between actors associated with BLM and far-right militants. This was the case in Greenville, South Carolina, for example, where opposing demonstrators confronted each other over a Confederate memorial on the city’s main street. A South Carolina bill from 2000, the ‘Heritage Act’, forbids the removal of any flag or memorial without a two-thirds vote from the state legislature. The result has been stagnation in the struggle over the downtown statue — and with it, a rise in outside armed counter-demonstrators opposing the local BLM chapter (Post and Courier, 7 August 2020; Post and Courier, 5 March 2021).

The fight over these and other statues has been highly animating for many right-wing actors, for whom the monuments represent a physical manifestation of a preferred version of American history and heritage (The Atlantic, 26 June 2020; Chicago Tribune, 9 April 2021; New York Times, 15 June 2020; Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 29 May 2020). This, in turn, pushed other grievances and fears to the surface as actors have taken to the street to defend this legacy, and, as such, their particular way of life; some note that the statues are not symbols of racism, but rather symbols of heritage and a way of life (KIRO7, 16 August 2017), with others comparing their removal to “cultural genocide.”6This refers to a late 2018 public presentation by a far-right, neo-Confederate organization’s ‘heritage’ officer, who described the “cultural genocide … conducted by mobs of neo-Marxists with the full support of the left-wing mass media” when discussing the prospect of removing or destroying monuments related to the Confederacy. This officer ironically used as an example a monument put up by segregationists in the 1960s, 100 years after the end of the Civil War. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, for example, demonstrations calling for the removal of a statue to a conquistador drew the New Mexico Civil Guard to the scene. At one of these protests, an armed man, who had been shoving protesters for hours, discharged his handgun at and seriously wounded a demonstrator (NPR, 17 June 2020; MilitiaWatch, 17 June 2020).

BLM-related demonstrations have been organized against statues7This refers to incidents resulting in substantial damage to the statue – rather than simply graffiti or other similar acts of minor vandalism — such as the breaking off of pieces or the toppling of the statue. in at least 18 states across the country (see map below). Virginia was a hotspot for such demonstrations, home to seven of these 30 incidents.8ACLED records 51 incidents of statues being targeted between 1 January 2020 and 30 April 2021. Of these, 30 were connected to demonstrations in support of BLM. The others include some cases in which individuals advocating for social justice or against racism, without association with the BLM movement, targeted statues — such as when individuals vandalized a Confederate statue in Clinton, North Carolina on 11 July 2020, partially pulling it down, before it was removed the same day by the County Courthouse (ABC11, 12 July 2020) — while others are at times in opposition to the BLM movement — such as when a statue of Breonna Taylor that supported the BLM movement was “smashed” in Oakland, California the weekend of 23 December 2020 (LA Times, 29 December 2020). Almost every one of the events in Virginia took place in Richmond, likely due to the high concentration of Confederate memorials in the city that served as the capital of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Armed Presence by Far-right Militias and Militant Social Movements

In addition to their involvement as demonstrators in counter-protests, militias and MSMs also began to show up at demonstrations not to protest, but rather in a self-proclaimed capacity to ‘keep the peace.’ Groups stated that they were standing by, armed, to protect businesses or the local community from ‘BLM rioters’ and the ‘violence and destruction’ of BLM-related demonstrations. In some cases, this mobilization is explicitly related to a group’s ideological positioning, where BLM is viewed as a ‘Marxist’ organization or as a group ‘puppet-mastered’ by now-President Joe Biden or even philanthropist George Soros (for example, see: Independent, 18 December 2020; Times of Israel, 15 September 2020). In other cases, militia groups and MSMs have perceived BLM demonstrations as destructive or violently threatening, either physically or to a way of life that they aim to preserve. Far-right channels, activists, and writers focus on the riots and property damage sometimes associated with these demonstrations and project them onto their own communities. This leads to aggressive action against BLM-related demonstrations when they come to a physical space shared with these right-wing organizers — or even in cases where activity is simply rumored to to take place. For example, in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, fears of traveling BLM and ‘Antifa’ demonstrators led armed white men to organize multiple vigilante patrols through the downtown area (Washington Post, 4 June 2020), despite the fact that no violent riots associated with the BLM movement have ever been reported in the city.

In many cases, it is difficult to identify which armed group is present at a demonstration, with reports often noting the mere attendance of such actors. In total, at least 25 distinct, named groups have shown up in this context over 40 times across 17 states since the start of last year, including in Georgia and Kentucky (see inset vignettes). Among identified actors, the groups most often spotted in these roles at BLM-related demonstrations include the Boogaloo Boys and III% factions. Others include the Stokes County Militia, the Proud Boys, and various identified local militia groups.

This type of protest involvement is different from direct engagement where militia groups and MSMs more formally take sides. In some cases (see inset vignettes), right-wing groups have attempted to act as auxiliaries for government authorities or to otherwise act as security services for private establishments. Most of the time, this type of activity takes the form of armed men standing across the street from demonstrations, watching participants but opting not to engage. In other cases, it can be more secretive, with right-wing actors taking to rooftops blocks away from demonstrations to observe and ‘patrol.’

Violent Individuals

Beyond organized militias and MSMs, violent individuals have also mobilized in opposition to the BLM movement. These include both decentralized, networked, armed individuals — such as those that may respond to ‘muster calls’ or ‘calls to action’ by organized militias — as well as violent sole perpetrators, acting independently.

Decentralized, Networked, Armed Individuals

Cases where armed and primed individuals have responded to networked calls to action have resulted in multiple shooting incidents targeting social justice activists and demonstrators supporting BLM since last summer. For example, Steven Ray Baca’s response to a muster call by the New Mexico Civil Guard in Albuquerque, New Mexico in June 2020, noted above, resulted in the shooting of a protester advocating for the removal of a statue that served for many as a symbol of racism and oppression (Guardian, 17 June 2020).

Another example is Kyle Rittenhouse’s response to a muster call by the Kenosha Guard in Wisconsin in late August of last year, which resulted in the deaths of two protesters and the injury of a third (New York Times, 16 October 2020). After the 23 August 2020 police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a resurgence in local demonstrations associated with BLM led to the return of loosely organized ‘vigilante’ militias to the city. This was primarily organized around the Kenosha Guard, an organization founded by a former Kenosha alderman, who issued a ‘militia muster’ for 25 August following violent demonstrations the previous day. Among those who responded to the call-to-action was Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year-old white male from just across the Wisconsin-Illinois state line. Rittenhouse came armed with an AR-15-style rifle and told a reporter during the evening that “we don’t have non-lethal,” indicating he was prepared to kill if the situation escalated (NPR, 27 August 2020). The evening did escalate, and Rittenhouse shot a man in the head before running up the street, falling to the ground, and shooting two other BLM-affiliated demonstrators. One of the men Rittenhouse shot had a handgun, which he never fired. Two of the three individuals shot by Rittenhouse died. After shooting the three men, Rittenhouse continued to flee down the street and crossed a police line without incident. He is now facing criminal charges related to his involvement in the Kenosha shootings.

Rittenhouse has been an important figure for Republican organizing and far-right community-building through memes, shared conversation, and radicalization (GNET, 29 October 2020). Then-President Trump defended Rittenhouse on 31 October, saying Rittenhouse “probably would have been killed” if he were not armed (CBS News, 1 September 2020). Trump’s defense of Rittenhouse allowed him to become a cause célèbre among Republicans, who largely refer to him as a “patriot,” “hero,” and a defender of “property owners” (Politico, 1 September 2020). The support for Rittenhouse even permeated government agencies, such as the Department of Homeland Security, which suggested officials note that Rittenhouse “took his rifle to the scene of the rioting to help defend small business owners” when questioned by the media (NBC, 1 October 2020). Among far-right organizations, such as the Proud Boys, Rittenhouse has become immensely popular. A group of Proud Boys serenaded him with renditions of “Proud of Your Boy” — the Proud Boys anthem — days after his 18th birthday at a Wisconsin bar (USA Today, 14 January 2021; ABC, 12 December 2018). His bail conditions were revised to prohibit him from socializing with Proud Boys after images of the incident surfaced, including one in which he flashed a white power hand sign (Washington Post, 14 January 2021, Wisconsin Public Radio, 14 January 2021).

Sole Perpetrators

In addition to individual responses to public calls to action, other violent individuals have taken to violence more sporadically. This type of activity — including car rammings, individual assaults, or ‘leaderless resistance’ modalities — has become increasingly common in the aftermath of Floyd’s killing.

The BLM movement has faced a particularly high rate of car-ramming attacks. Car rammings are eight times more common at demonstrations associated with the BLM movement than at other types of demonstrations, with incidents reported at nearly 1% of all BLM-related events. At least 91 pro-BLM demonstrations were met with car rammings between the start of last year and the end of April 2021, while car rammings were only reported at 14 non-BLM demonstrations during this period. Although car rammings targeting BLM supporters have declined since their height in May and June 2020 during the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s killing, they continue to be reported. Just last month, while people were demonstrating in support of the BLM movement in Minneapolis, Minnesota against the police killing of Daunte Wright, a Black man, a truck driver reportedly drove his car through the demonstration (Free Republic, 14 April 2021).

The prevalence of car rammings is partially due to the disinformation surrounding the BLM movement and the supposed violence that demonstrators perpetrate against bystanders. Trump supporters, such as those participating in MAGA Drag or MAGA Caravan events — where dozens of drivers, sometimes tied to far-right MSMs, such as III% groups, Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, or Patriot Prayer, would pass through cities or along highways in support of President Trump during election season last year — have said that they felt compelled to join such events to demonstrate they represented a “silent majority” who oppose “BLM garbage” (NPR, 24 September 2020; MilitiaWatch, 16 April 2021). Displays against the BLM movement or against antifascists have been prevalent at such demonstrations (KSAT12, 8 September 2020; Daily Mail, 2 November 2020; Twitter @LRedSchoolHouse, 1 November 2020). Car-ramming attacks on the BLM movement have been glorified and encouraged online, such as through the “All Lives Splatter” meme (Bloomberg, 3 June 2020). In recent months, lawmakers in multiple states — such as Florida and Oklahoma — have introduced or enacted new legislation that would grant “immunity to drivers whose vehicles strike and injure protesters in public streets,” expanding legal protections for individuals involved in car ramming incidents (New York Times, 21 April 2021). Critics of these legal measures warn that they effectively enshrine the “right to crash cars into people” and “endorse a terrorist tactic against protesters” (New Republic, 24 April 2021) (see section on “anti-protest” legislation above).

Officials and drivers have justified car rammings — and the new legislation protecting them — as part of an effort to combat “public disorder” and “riots” (VICE, 19 April 2021). Yet, while the rate of car rammings at demonstrations involving reports of violence, vandalism, looting, or other destructive activity is highly correlated, the vast majority — 73% — of BLM-related protests that faced car-ramming attacks were peaceful. The visual below depicts all demonstrations associated with BLM in which car rammings were reported, colored by whether destructive activity was reported at the event. New legal cover in states like Florida and Oklahoma raises the risk that car-ramming attacks on peaceful protests will only increase during future demonstration spikes.

Looking Forward

In the aftermath of Floyd’s killing, demonstrations associated with the BLM movement proliferated across the country, with a spike in both the number of demonstration events (black line in graph below) as well as the number of states home to these demonstrations (orange area in graph below). Following the subsequent crackdown on BLM activism, demonstrations associated with the movement diminished, as did their geographic spread across the country. However, in recent months, the number of BLM-associated demonstrations, as well as the geographic spread of these events, has begun to rise and expand again (see graph below).

Last month, over 500 pro-BLM demonstrations were reported around the country — more than in any month since September of last year. One of the drivers behind this upward trend was the trial of Derek Chauvin — the former police officer ultimately found guilty for murdering George Floyd — which spurred a resurgence of national-level organizing. An Ipsos snap poll in the hours after the guilty verdict indicated that Americans overwhelmingly approved the decision at 71% (USA Today, 21 April 2021).

At the same time, the verdict came on the heels of a series of new police killings of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). Organizing around these killings also contributed to the recent spike in pro-BLM demonstrations, with the Chauvin trial conducted in stark juxtaposition to the shooting of Daunte Wright, for example, which took place on 11 April in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, not far from Minneapolis where Floyd was killed (AP, 14 April 2021). Other contemporaneous police killings included that of Adam Toledo on 29 March in Chicago, Illinois (AP, 15 April 2021); Mario Gonzales on 19 April in Oakland, California (Mercury News, 27 April 2021); Ma’Khia Bryant on 20 April in Columbus, Ohio (CBS News, 22 April 2021); and Andrew Brown, Jr. on 21 April in Elizabeth City, North Carolina (NY Times, 28 April 2021); among others.

Despite the Chauvin verdict, the Black community continues to face discrimination and police violence. Police officers continue to enjoy widespread impunity for abuses of power (NBC, 21 April 2021). And the country continues to grapple with the threat of white supremacy — and particularly its intersections with government and law enforcement — in the wake of the Capitol attack (AP, 14 January 2021).

Having sustained protests for a year since Floyd’s murder, the BLM movement will continue as well. Demonstrations are on the rise again, and some activists and politicians claim that police reform has gained “momentum” in the aftermath of Chauvin’s trial (CBS, 21 April 2021). Conversely, even as 95% of all pro-BLM demonstrations since the start of this year have been non-violent — suggesting that the protests have only gotten more peaceful — 41% of Americans remain opposed to the movement (Civiqs, 18 May 2021), meaning that disagreement and disinformation around its core goals will continue to fuel tension. Simultaneously, lawmakers have pushed forward with new legislation that will only make it more difficult for peaceful protesters to mobilize, all while enabling a more forceful crackdown on future activism. A year on from Floyd’s death, the unrest of 2020 is far from over the horizon.

The need for the real-time monitoring of these trends has never been more crucial, and ACLED will continue to offer public access to the latest data on American political violence and protest patterns as they evolve.