Tracking Disorder During Taliban Rule in Afghanistan

A Joint ACLED and APW Report

14 April 2022

To address sourcing challenges in Afghanistan after the Taliban seized power, ACLED has worked with APW to adapt our methodology to reflect the evolving political violence landscape on the ground and enhance coverage of emerging conflict developments. This joint report examines key trends in violence targeting civilians, particularly political violence targeting women, as well as clashes between Taliban and anti-Taliban forces, including the Islamic State, in the first seven months since the fall of Kabul.

This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

Download PDF:

Scroll down to read online.

Introduction

After the 15 August 2021 fall of Kabul to Taliban forces, violence towards civilians has persisted in Afghanistan. As a result of the heightened risk of violence targeting civilians under Taliban rule, Afghanistan is included in ACLED’s 10 conflicts to worry about in 2022, in part due to the particularly high level of violence targeting women in politics, specifically women who aim to prevent the erosion of the rights of women and girls. Amid ongoing concerns over civilian targeting and an increasingly repressive context for reporting, acquiring information on risks has been severely impacted. Organizations tracking political violence and protests have thus had to adapt to the changing environment to adequately capture trends on the ground.

This report reviews the challenges of sourcing data in Afghanistan in the seven months after the Taliban takeover. It highlights the contribution of Afghan Peace Watch (APW) data to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) dataset, examining how key trends concerning violence targeting civilians, particularly political violence targeting women, are better captured as a result of adaptations made to reporting and sourcing data. The report includes an overview of the clashes that have occurred between Taliban and anti-Taliban forces, as well as between the Taliban and the Islamic State (IS), since the Taliban came to power. Data on Taliban infighting is also reviewed to understand the degree of cohesion in the group as they move from insurgents to the de facto government.

ACLED and APW

ACLED tracks political violence and protest events around the world in real time. ACLED relies on a wide range of trusted sources to code events, adapting as contexts evolve so as to better capture trends on the ground. ACLED’s Afghanistan data cover 1 January 2017 to the present.

APW is a local conflict observatory established in 2020 which has expanded its scope to monitor developments on the ground in Afghanistan through a strong network of reporters. APW offers credible information on protests, human rights violations, and other security matters.

ACLED and APW formalized a partnership in February 2021.

Adapting Sourcing After the Fall of Kabul

Gathering information and reporting on political violence and protests has become more challenging since the Taliban seized power, as many local media outlets in Afghanistan have either collapsed or been strictly censored by the Taliban. The International Federation of Journalists estimates that over 300 media outlets have closed since 15 August 2021 (IFJ, 3 February 2022). Outlets that do remain open face censorship, unable to report on the reality of the situation on the ground. Those who take the risk to report news contradicting the Taliban narrative can find themselves threatened, jailed, and/or tortured by the Taliban.

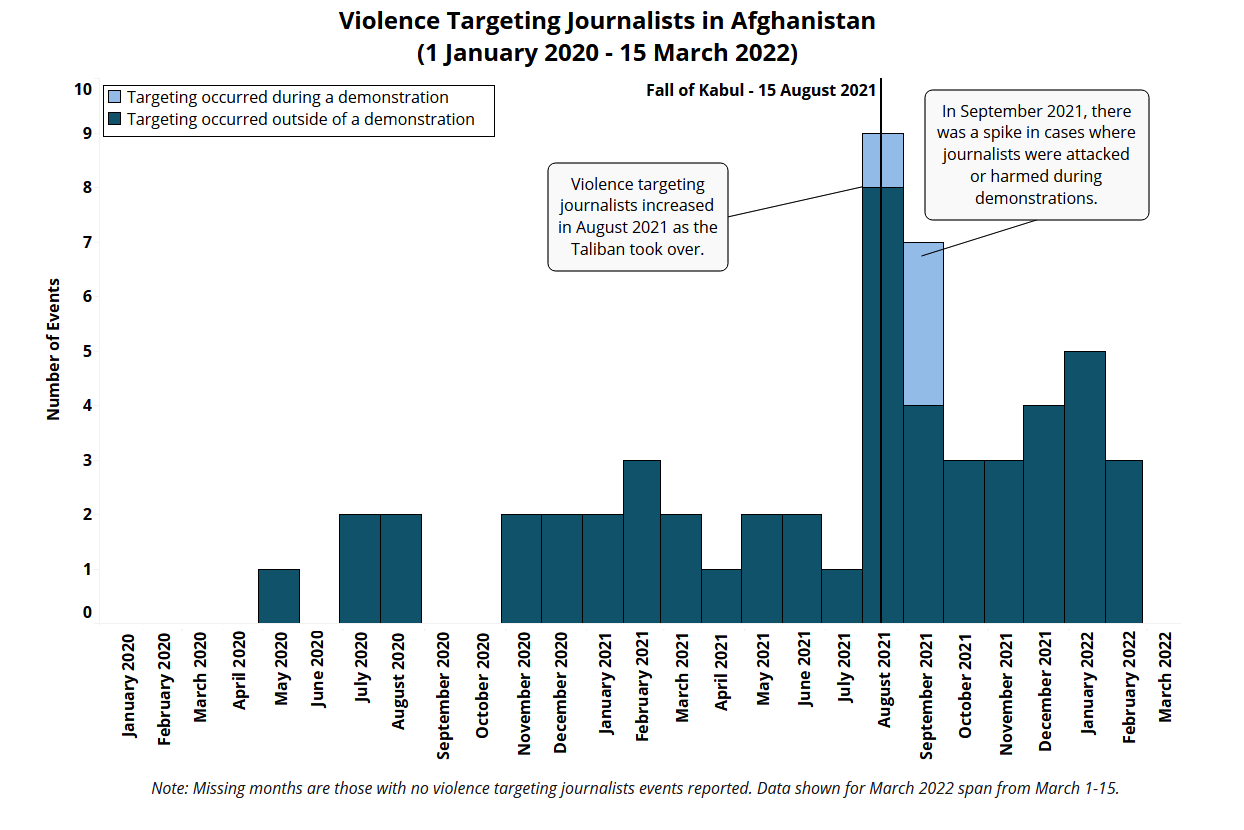

According to ACLED data, violence targeting journalists reached a high in August 2021 as the Taliban took over (see figure below). Journalists have notably been targeted while covering demonstrations against the Taliban, particularly those led by women. ACLED records an increase in cases where journalists were attacked or harmed during demonstrations (in light blue in figure below) in September 2021.

This repressive media environment has forced organizations monitoring political violence and protest in the country to adjust in order to accurately capture the reality on the ground. As ACLED moved to adapt to the changing media landscape after the fall of Kabul, it expanded its sourcing through the addition of new traditional media sources in several local languages, as well as deepening its use of forms of ‘new media,’ specifically social media. In addition, ACLED has strengthened its partnership with local conflict observatory APW which likewise adjusted its reporting practices amid an increasingly repressive local context. This section of the report further examines the adjustments made to reporting and sourcing amid a challenging, changing political environment.

Incorporating ‘New Media’ and Local Language Sources

ACLED does not crowdsource information from social media. ACLED’s established practice of identifying and vetting ‘new media’ accounts is employed in Afghanistan to identify additional social media accounts that could be sourced amid the repressive press environment. A key challenge encountered with ‘new media’ is the need to continuously test source accounts, as accounts will often emerge and disappear quickly, each with varying degrees of reliability. As such, ACLED is constantly in a cycle of identification, verification, and confirmation of new social media accounts.

When respected journalists or organizations that ACLED follows share information on social media from another social media account, that account that originally shared the information is itself assessed. ACLED also proactively reaches out to experts in the region to confirm the trustworthiness of such new social media accounts and to identify additional accounts that report on relevant events. All ‘new media’ accounts are then test sourced for at least four weeks to determine the degree of bias of the account; the timeliness of the account’s reporting; and the quantity of events likely to be coded if the account is added to ACLED’s source list (to ensure the cost-benefit of expending resources on such review). These measures help to determine whether the new source should be added to ACLED’s weekly source review processes. ACLED currently draws on information from over two dozen social media accounts, whereas previously the only social media accounts that ACLED primarily sourced information from were the social media accounts of newspapers and other traditional media outlets on ACLED’s source list.

Biases must be accounted for when sourcing. For example, reported fatalities from events based on Twitter accounts of the National Resistance Front (NRF), an anti-Taliban group, are typically higher than counts reported by other sources, with sporadic claims of over a hundred casualties after some clashes. To mitigate this apparent bias, corroborated by external experts, a methodology specific to NRF-related Twitter accounts was developed.1 For more about this methodology, see ACLED’s Afghanistan methodology document.

Alongside the addition of new social media sources to ACLED’s source list, ACLED places an increased emphasis on local traditional media sources reporting in Dari, Pashto, and Arabic as well. This has allowed ACLED to code events from smaller news agencies reporting on Afghanistan. ACLED events are coded based on reports directly sourced from the local language websites, rather than solely those found in larger news aggregators. This contributes to continuous and full coverage.

Strengthening Local Conflict Observatories

ACLED also relies on local partners to provide information on events that would otherwise remain unreported. In light of the repressive environment in Afghanistan, APW, a local conflict observatory and ACLED partner, adapted its information collection practices, expanding to report on disorder beyond armed conflict. While the Taliban takeover initially necessitated a slowdown in APW’s work in order to prioritize the security of its staff, as APW has restarted its work, over 800 new events have been collected since late December 2021.2APW data are coded in the ACLED dataset according to ACLED’s established methodology. This may lead to more or fewer events being coded in the ACLED dataset based on information collected by APW given different inclusion criteria and methods of aggregation/disaggregation. For more on ACLED methodology, see the ACLED Codebook. APW has drawn on its wide network of sources on the ground to gather information, continuously cultivating new sources at a provincial level. APW has expanded the number of sources it draws from in each of the 34 provinces in Afghanistan and aims to cultivate sources across all of the country’s 421 districts as well. APW sources include journalists, activists, former officials, and chieftains, among others.

In addition, APW has extended its media monitoring activities. APW draws from over 120 media sources, including two dozen news websites and around 100 Twitter and Facebook accounts. Some of the social media accounts that previously provided extensive information on the conflict in Afghanistan, but which had gone silent since the Taliban takeover, were contacted by APW for information on events. APW is also mindful of the use of disinformation, particularly by the Taliban, which poses a challenge to collecting accurate information. As such, APW uses a verification process for sources on the ground, which increases the reliability of events reported.

Another challenge that APW has encountered in its reporting is determining the right time to include previously unreported events; families of affected individuals often choose to keep quiet to avoid further harm to their loved ones. For example, the Taliban may detain civilians without providing a reason for their detention. In such cases, families may seek the assistance of elders to intervene on their behalf to secure the release of the detained family member without making their detention or abuse known to the media. This self-censorship can prevent events from being reported immediately. APW has adapted to this by maintaining contact with sources and waiting to report on such events when the immediate security of the individual is no longer a concern.

Given this potential delay in reporting due to security concerns, APW engages in a continuous backtracking process to collect data. For example, in late February and early March 2022, APW added nearly 70 events to its dataset from previous months that could not be reported on initially. To further ensure the security of sources, APW encourages anonymous reporting to avoid respondents becoming Taliban targets. This approach has allowed APW to collect information that would have otherwise gone unreported.

New Trends from the Inclusion of APW Data in the ACLED Dataset

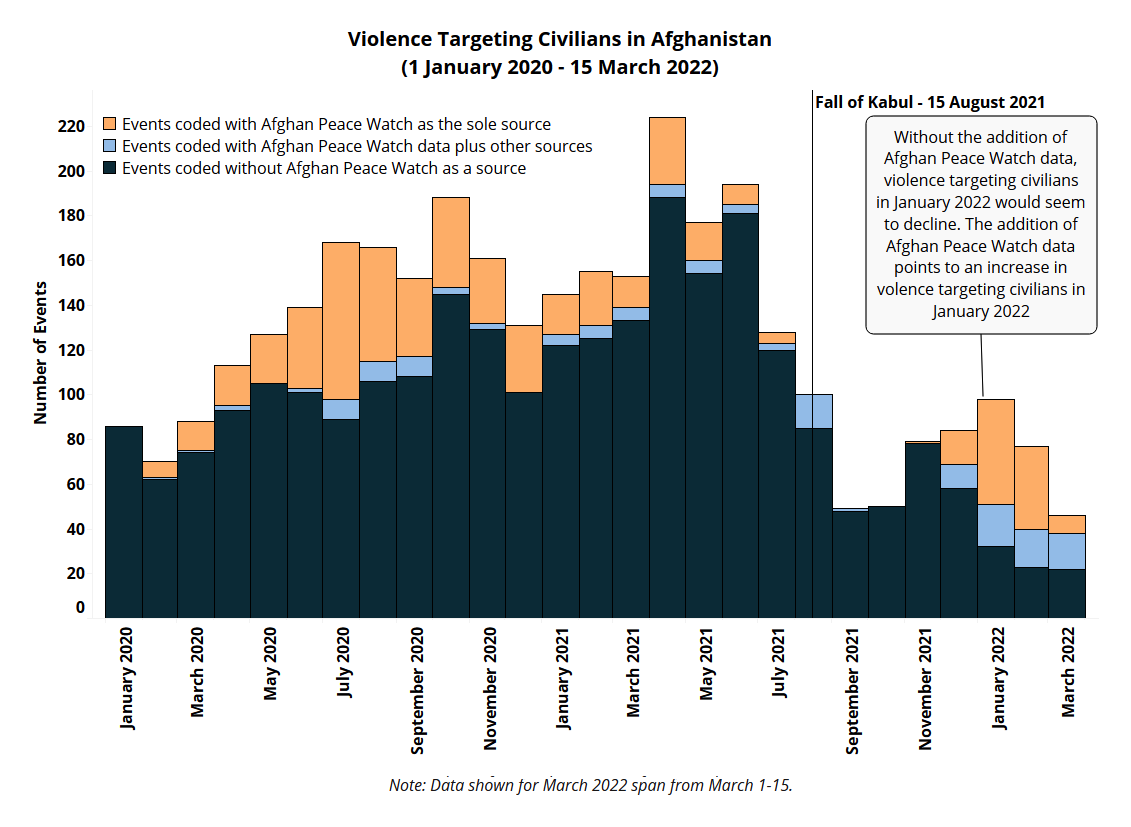

ACLED’s adaptations to its sourcing, as noted above, have contributed to maintaining a dataset that accurately reflects political disorder in Afghanistan. ACLED’s ability to track violence targeting civilians after the fall of Kabul has been particularly bolstered by APW data, with over 20% of such events coded by ACLED reported solely by APW. The potential for an increase in violence targeting civilians, particularly political violence targeting women, under a Taliban government3From 16 August 2021 on, ACLED codes the Taliban as Government of Afghanistan (2021-) with their forces coded as Military of Afghanistan (2021-) and Police Forces of Afghanistan (2021-) given their de facto control of the country. This is not meant to denote legitimacy or international legal recognition, but rather acknowledges the fact that a distinct governing authority exists and exercises de facto control over significant portions of territory in a country. As a result of the Taliban being coded as the de facto government in Afghanistan, the coding of some sub-event types changes as well. Up to 15 August 2021, Taliban forces seizing control of a territory in a battle is coded as: Non-state actor overtakes territory. After 15 August 2021, Taliban forces taking control of a territory in a battle is coded as: Government regains territory. has been a key concern for many.

Without APW data, violence targeting civilians by all actors in January 2022 would seem to decline. The addition of APW data, however, points to an increase in such events in January 2022 (see annotation in figure below).

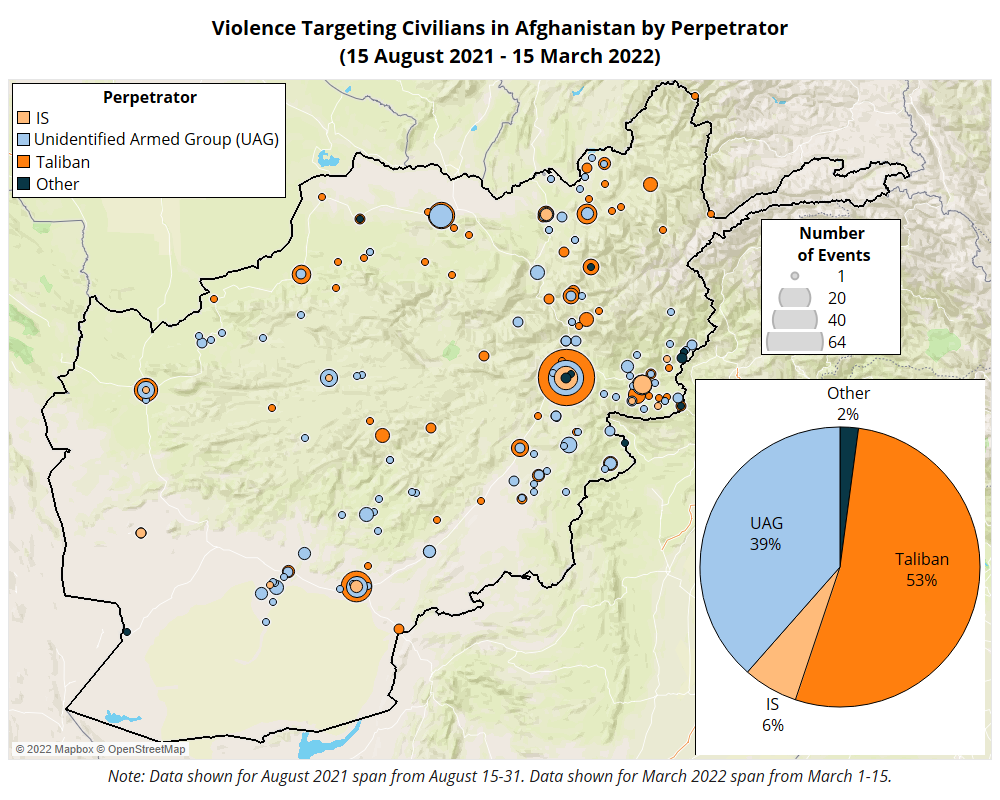

Tracking Violence Targeting Civilians

Since the fall of Kabul, civilians have continued to be targeted by the Taliban and the Islamic State (IS), as well as by unidentified armed groups. The Taliban has been the main perpetrator of violence targeting civilians4Violence targeting civilians is defined by ACLED as inclusive of Violence against civilians, Explosions/remote violence, and Riots events with interaction terms including 6 (peaceful, unarmed protesters) or 7 (unarmed civilians). The sub-event type Excessive force against protesters is also included. For more on event types, sub-event types, and interaction terms used in the ACLED data, see the ACLED Codebook., perpetrating over half of the violence targeting civilians recorded by ACLED since 15 August 2021 (in orange in figure below).

Civilians have been targeted for their profession, ethnicity, and religion. Most notably, former government officials and security forces have been targeted, with nearly 30% of Taliban violence targeting civilians directed towards such individuals since 15 August 2021. Many have been detained and held incommunicado5When a former government official or member of the security forces is detained by the Taliban and no information is provided about where he or she is held, ACLED codes this event as: Abduction/forced disappearance. (Human Rights Watch, 30 November 2021). Their families also face abuse. In one case, the brother of a senior security officer was killed when the Taliban could not reach the officer himself; the officer had reportedly fought on the frontlines against Taliban forces in past years (Shafaqna, 1 March 2022).

The Taliban has also targeted tribal and minority communities perceived to support previous governments, forcibly seizing land belonging to such communities. Hazaras, Uzbeks, and Tajiks have been targeted due to their participation in anti-Taliban alliances in the 1990s (Gandhara, 9 December 2021). The Taliban has been accused of seizing and redistributing land to communities supporting the group, such as Pashtun tribes (Human Rights Watch, 22 October 2021).

The second most common perpetrators of violence targeting civilians in Afghanistan since the fall of Kabul are unidentified armed groups. Since 15 August 2021, 39% of violence targeting civilians recorded by ACLED has been committed by unidentified armed groups.6ACLED codes events involving unidentified armed groups where the violence is believed to be political, not criminal. This can be determined by the history of a particular location, the occupation, ethnicity, or tribal connections of the targets of the violence, threats made prior to the violence, and/or the method of violence used by particular perpetrators. If more information emerges later about an event that points to it being politically motivated, then an event that was initially thought to be non-political and thus not included in the dataset may be added to the data. Likewise, if events are initially thought to be political, but later found not to be, they are removed from the dataset. Violence perpetrated by such groups includes attacks, abductions, and assassinations. Armed groups may favor anonymity when targeting civilians so as to distance themselves from violence and its social consequences (ACLED, 9 April 2015).

Political Violence Targeting Women since the Taliban Takeover

Since the Taliban seized power, there have been fears that political violence targeting women and girls will increase under Taliban rule given the Taliban’s traditional position on the rights of women and girls. The strict interpretation of Islamic Law adopted by the Taliban heightens the risk of political violence targeting women and girls. After the Taliban takeover, many demonstrations in support of women’s rights – including the right of girls to go to school – and against the Taliban government have been held. ACLED records over 80 demonstrations featuring women since the Taliban takeover in comparison with only three recorded in 2021 prior to the Taliban takeover.

Many women activists have been targeted specifically for their participation in these demonstrations. For example, on 18 January 2022, a woman civil society activist was killed by unknown gunmen near her house in Mazar-e-Sharif city, Balkh, after protesting against the Taliban government with other women in recent months. The following day, Taliban intelligence forces raided the houses of several women’s rights activists in Kabul after they participated in demonstrations in support of women’s rights and against women being forced to wear the hijab. While in detention, the women were abused, with at least one woman seriously beaten (Baaghi TV, 20 January 2022).

Despite the Taliban’s efforts to quell demonstrations for women’s rights, many women have adapted their protests to the repressive environment. To avoid being targeted by the Taliban, women have organized demonstrations which disperse quickly and have taken precautions to ensure the activist networks used to organize such demonstrations are not infiltrated by Taliban informants (France24, 9 February 2022). Women have also taken to staging demonstrations in private spaces, such as their homes. These indoor demonstrations involve women holding signs with protest slogans while they give speeches that are recorded and shared with the media (Gandhara, 8 December 2021). ACLED records over 20 indoor demonstrations since the first one was reported in late November 2021.

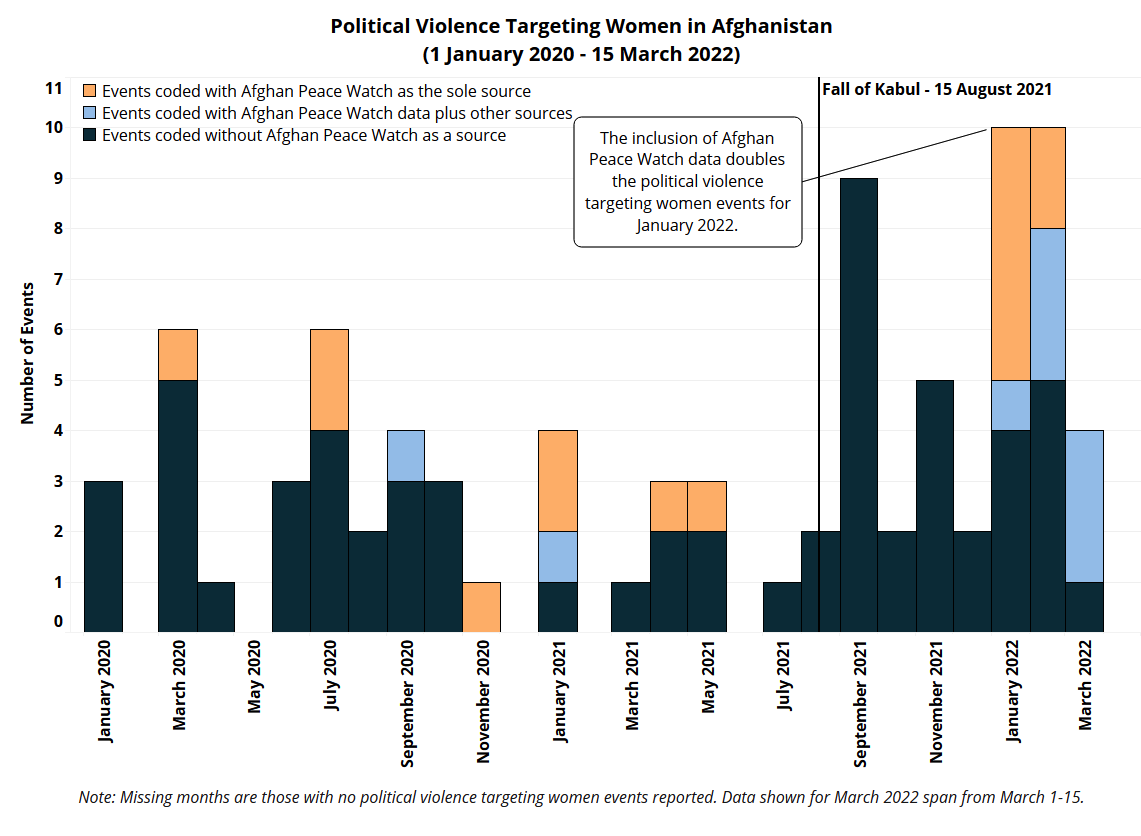

As with violence targeting civilians more broadly, tracking political violence targeting women since the Taliban takeover has been strengthened by the addition of APW data. The inclusion of APW data doubles the number of political violence targeting women events in the ACLED dataset for January 2022 (in peach and light blue in the figure below).

In January and February 2022, ACLED recorded the highest number of political violence targeting women events since the start of ACLED coverage in 2017. Of the political violence targeting women in early 2022, as of 15 March, 75% of recorded events are perpetrated by the Taliban, with the remaining 25% committed by unidentified assailants. Political violence targeting women by the de facto Taliban government already exceeds previous years of state violence targeting civilian women in the ACLED dataset back to 2017. ACLED data thus support the concern that women face increased violence under the de facto Taliban government (see figure above).

Subnational Patterns of Violence Targeting Civilians

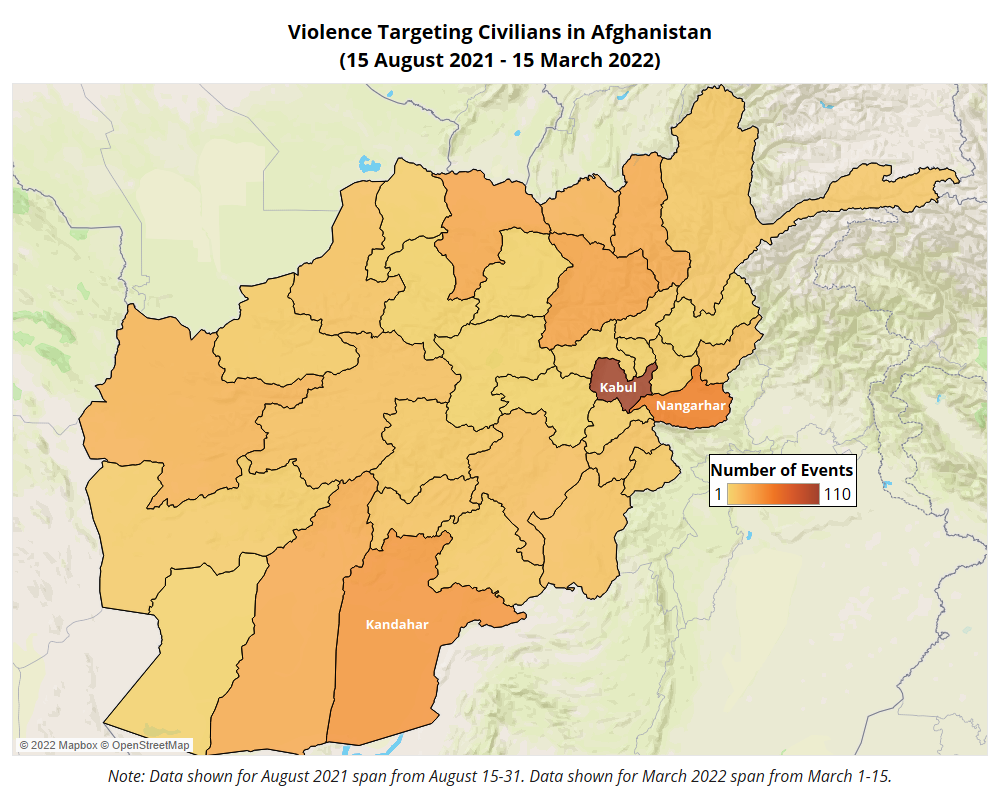

Patterns of violence against civilians vary subnationally in Afghanistan (for more, see ACLED’s Subnational Threat & Surge Trackers, part of ACLED’s Early Warning Research Hub). Since 15 August 2021, Kabul, Nangarhar, and Kandahar have experienced the highest levels of reported violence targeting civilians, according to ACLED data (labeled on the map below). Kandahar, the birthplace of the Taliban, and Kabul are the largest cities in Afghanistan, and the highway connecting the two has long been the site of violence (The Washington Post, 20 December 2021). Meanwhile, the eastern province of Nangarhar is an IS stronghold, with IS militants frequently targeting civilians in the area.

With reporting on numerous provinces having been impacted by the crackdown on the media, it is likely that the concentration patterns of violence targeting civilians are partly a function of the available reporting. In particular, rural areas outside major cities may experience more violence than reported. Outside Kabul, provincial media outlets are compelled to seek permission from provincial authorities before publishing reports, resulting in the censoring of information (Afghan Analysts Network, 7 March 2022; Human Rights Watch, 7 March 2022). The Taliban has taken a hard line against the publication of any information on their activity which contradicts their established narrative.

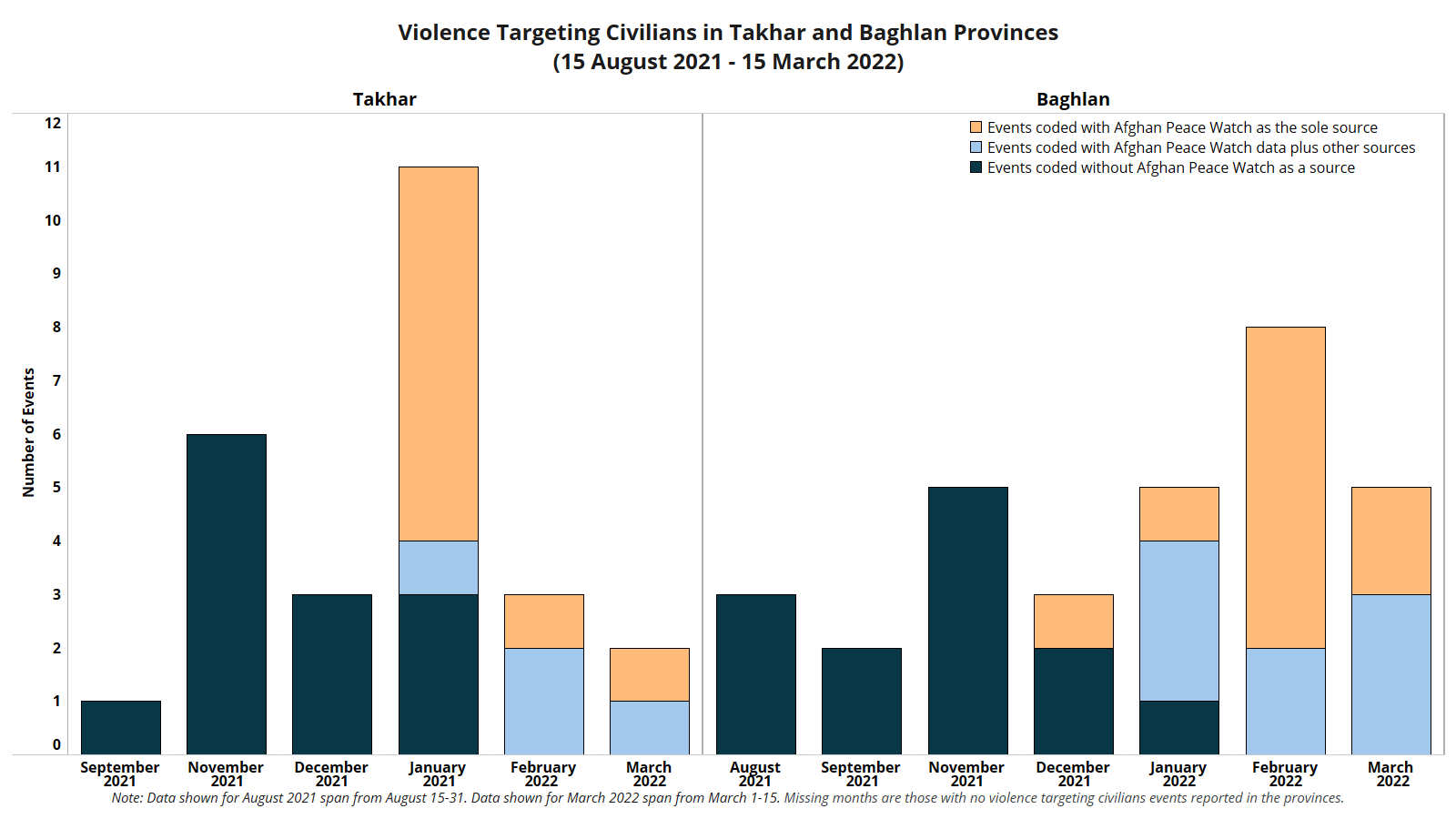

While there may be fewer events reported in some provinces compared to others, many provinces have seen an increase in violence targeting civilians since the Taliban takeover. In the north of the country, which has been the epicenter of anti-Taliban resistance, Takhar and Baghlan have experienced notable increases in violence targeting civilians in the first months of the year. With the inclusion of APW events, data show that violence targeting civilians spiked in January 2022 in Takhar and increased in Baghlan in February 2022 (see figure below). This rise in violence targeting civilians coincides with a rise in clashes between the Taliban and anti-Taliban groups in the regions. Many attacks follow such clashes as the Taliban often raids the homes of civilians, arresting those who are believed to support the anti-Taliban groups.

Tracking Emerging Anti-Taliban Actors, IS-Taliban Clashes, and Taliban Infighting

National Resistance Front and Emerging Anti-Taliban Forces

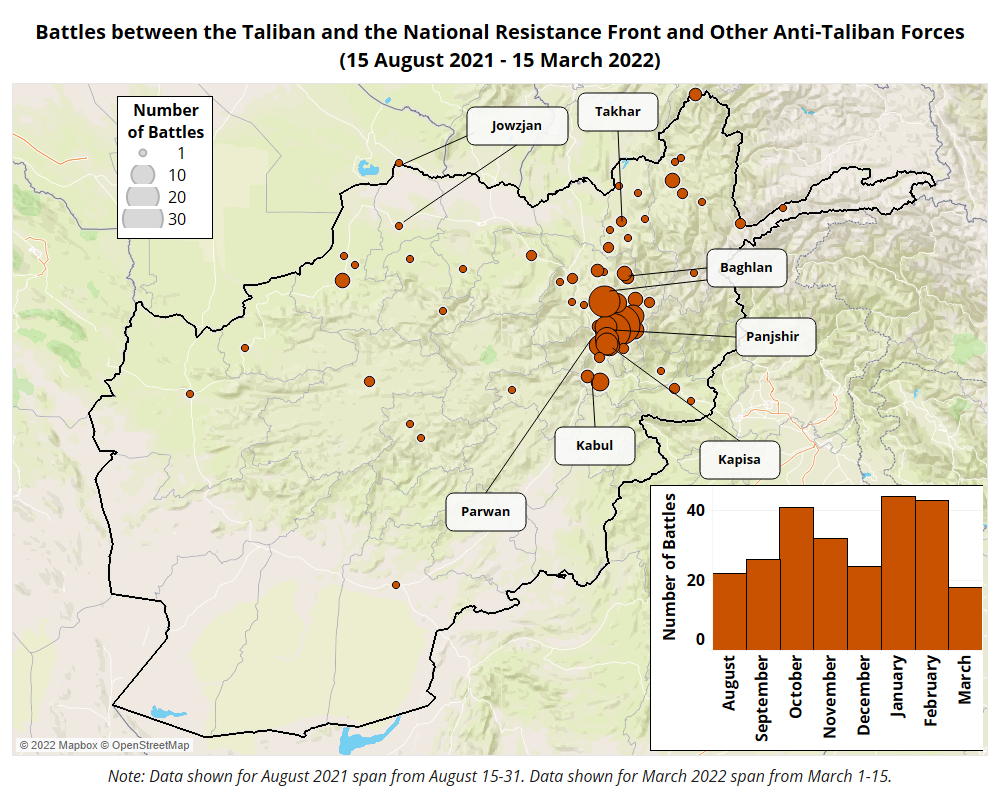

Since the Taliban came to power, new actors have emerged to contest Taliban rule. A key armed group that has emerged is the NRF, which was formed in the Panjshir valley by the son of Ahmad Shah Massoud, a leader in the resistance to the Taliban in the 1990s (The Diplomat, 15 December 2021). Mobilizing against the Taliban, the NRF has been active in the northern provinces of the country, including Panjshir, Kapisa, Baghlan, and Parwan (see map below). Clashes between the NRF and the Taliban increased in January and February 2022. APW has reported on over a dozen NRF-Taliban clashes, diversifying sourcing for such clashes which has previously been reliant to a certain extent on the NRF’s own reporting. The addition of the APW reporting contributes to making the ACLED data less dependent on an active, and biased, conflict actor for information.

In addition to the NRF, new anti-Taliban armed groups have emerged, though there is limited information about the size and operational capacity of such groups. Some groups have announced their formation and name publicly. As of 25 March 2022, ACLED records six such groups, with one reported solely by APW. These groups have carried out attacks on the Taliban, inflicting casualties.

For example, a group called the Turkestan Freedom Tigers carried out an attack on the Taliban on 7 February 2022 in Sheberghan city, Jowzjan (see map above). Also in February 2022, a group called the Afghanistan Freedom Front declared their formation and have since carried out attacks on Taliban forces in the northern provinces of Takhar, Kapisa, and Parwan (see map above) (Twitter @AfgFreedomAFF, 15 March 2022).7Clashes involving the group have occurred after 15 March 2022, which is the temporal scope of this report. In addition, the Afghanistan Liberation Movement recently emerged in eastern Afghanistan (Twitter, @aamajnews24, 23 February 2022). Unlike the NRF, the Afghanistan Liberation Movement is a Pashtun-led resistance group fighting against the Pashtun-majority Taliban. This is a notable development as resistance against the Taliban has largely been led by non-Pashtuns. It remains to be seen how active these groups will be going forward.

Some anti-Taliban groups that have formed remain anonymous.8ACLED records unnamed groups that are anti-Taliban with the generic actor “Anti-Taliban Forces.” This actor is assigned an interaction code of “2” indicating a group trying to overthrow the de facto state. This actor is coded when unspecified resistance groups, explicitly reported to be formed to fight the Taliban, engage in violence and/or declare their support for larger, organized armed groups such as the NRF. For more on ACLED interaction codes, see the ACLED Codebook. Those that have declared allegiance with the NRF have had their activity reported on by NRF-related Twitter accounts (Twitter @Resist_Ahmad, 19 November 2021). Other groups have positioned themselves as anti-Taliban, but are not associated with the NRF. The NRF has reported on the actions of some of these groups; ACLED and APW continue to track the emergence and activity of anti-Taliban groups.

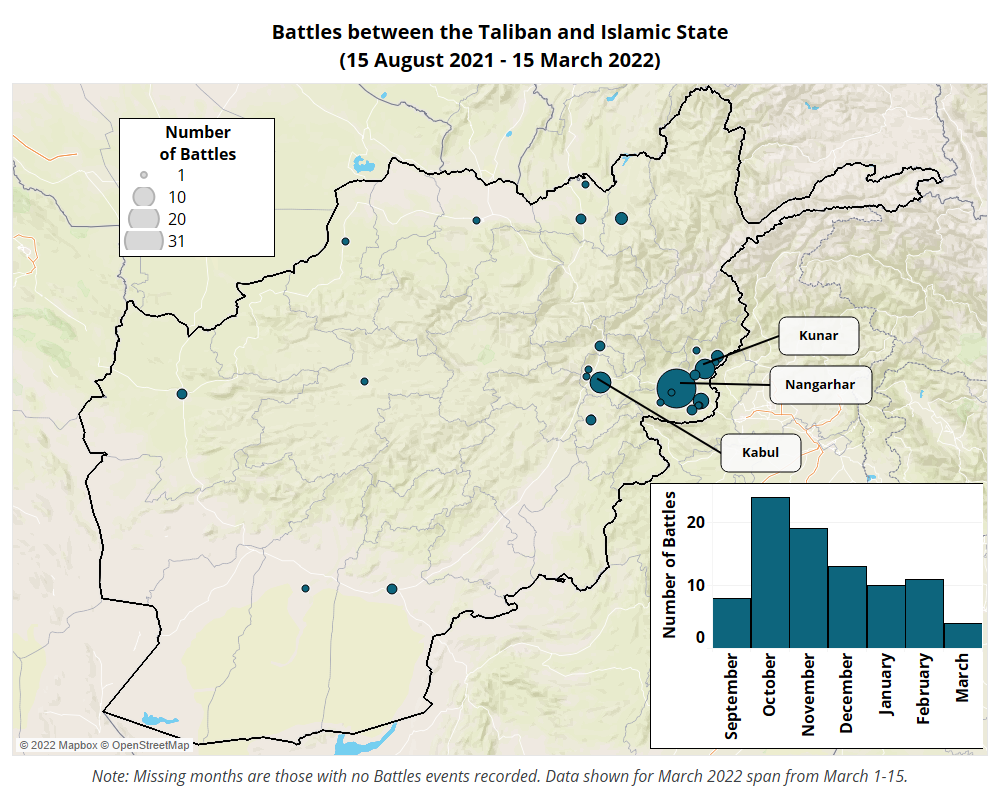

Islamic State-Taliban Clashes

The IS insurgency in Afghanistan has resulted in clashes with the Taliban, and these have increased since the fall of Kabul.9ACLED’s data on IS attacks have been enriched by the recent addition of data from ACLED partner ExTrac, which documents attacks and claims by IS. For more, see this recent ACLED infographic. IS activity has traditionally been concentrated in Kabul, Kunar, and Nangarhar in the east (see map below). ACLED has recorded IS activity, beyond armed clashes alone, in the north and west as well, though it is less prevalent. Violence targeting civilians involving IS was recently reported in Farah province, where ACLED had not previously recorded any direct IS attacks.

IS has also become active in Kandahar and Paktia province. In early January 2022, the group distributed leaflets in Kandahar’s Spin Boldak, warning people not to support the Taliban and vowing to take control of the area. The month before, in late December 2021, six IS affiliates were killed and two Taliban forces were wounded in a series of Taliban raids on four IS hideouts in Kandahar city, which sparked clashes between the two sides. In early March, a bomb went off shortly after Friday prayers in front of a mosque in the Kharoto area of Patan district in Paktia province, killing two worshipers and wounding six others. While no group claimed the attack, it had the hallmarks of previous IS attacks on mosques.

As more IS attacks are expected during the summer, which is the traditional fighting season in Afghanistan, arbitrary arrests by the Taliban of civilians, often accused of having links to IS, are increasing. In Paktia, the Taliban arrested four members of a family in late January over alleged links to IS in Paktia’s Chamkani district, just as they returned home from Nangarhar after 10 years.

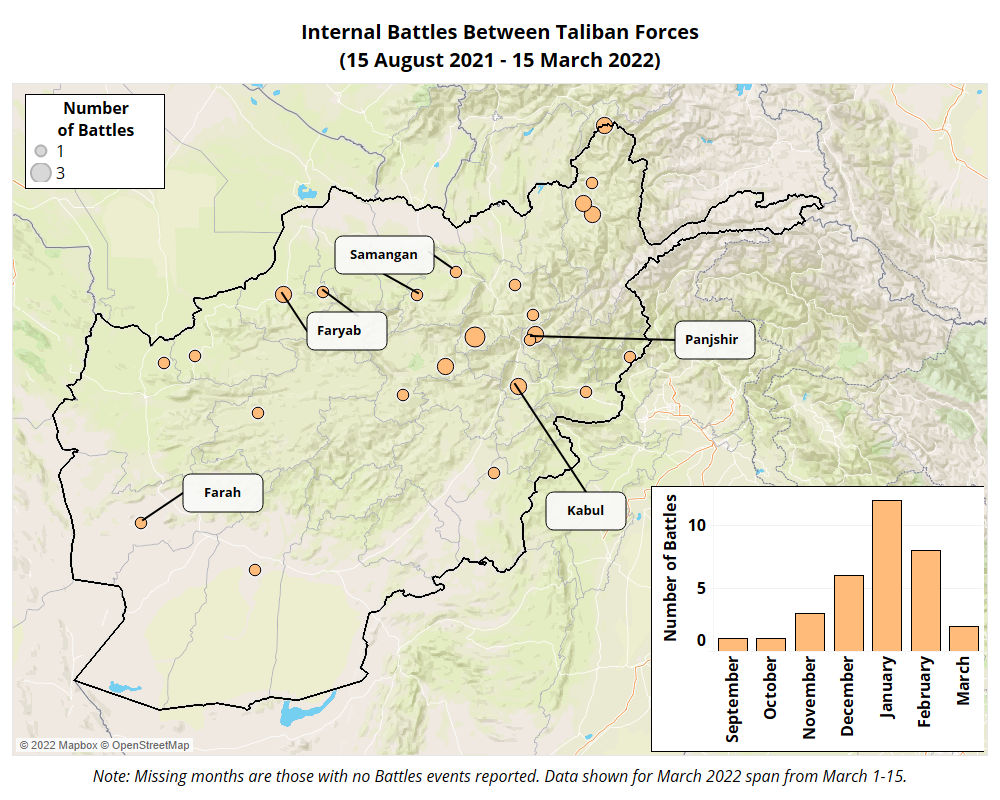

Taliban Infighting After the Fall of Kabul

Aside from external armed resistance to the Taliban, there are also significant internal challenges the group faces. The degree of infighting between Taliban forces since the fall of Kabul is an important trend given the Taliban’s prioritization of internal cohesion as it seeks to establish itself as the ruling government (CTC Sentinel, November 2021). Since the group seized power, ACLED records 33 events where Taliban forces engaged in clashes with each other — a significant increase from trends seen prior to the Taliban takeover of Kabul (see map below). Of the 33 events, 13 were reported by APW alone, including events in Farah and Samangan provinces. ACLED has not previously recorded significant activity in these two provinces, especially after the Taliban takeover. APW data are integral in expanding coverage of Taliban infighting in these regions.

The first infighting event ACLED recorded after the Taliban takeover was in early September 2021. A clash occurred in Kabul during cabinet-forming meetings between forces loyal to Taliban co-founder and Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar and those loyal to the Minister for Refugees Khalil ur-Rahman Haqqani, a leader in the Haqqani Network. The event has not been further remarked upon by Taliban officials. While the Haqqani Network has long supported the Taliban, and now occupies high-level positions in the Taliban’s interim government (War on the Rocks, 12 November 2021), this event points to tensions between these two factions within the Taliban.

Additionally, several Taliban infighting events recorded by ACLED are in areas where the NRF has been active (see map above). The NRF has reported that some local Taliban commanders joined the NRF with their troops and military equipment in early January 2022 (Twitter @Resist_Ahmad, 6 January 2022). As well, some local Taliban members from Panjshir province, unhappy with Taliban actions, have left the Taliban or were dismissed because they were not Pashtun (Twitter @Akhbar_Afghan 24 November 2021; Twitter @Resist_Ahmad, 26 November 2021).

Meanwhile, Taliban infighting has also occurred due to ethnic fault lines within the group. Although the Taliban predominantly consists of fighters of Pashtun ethnicity, the group has commanders and members of other ethnicities. As the Taliban moves its mainly Pashtun members into different provinces after coming to power, tensions between the local communities and Taliban members arise (RFE/RL, 29 January 2022). In January 2022, ACLED recorded a clash between Uzbek and Pashtun Taliban groups in Faryab province, where Uzbeks are the majority ethnic group (see map above) (European Union Agency for Asylum, December 2020). The Taliban later sent troops to Maimana city to ensure stability. Several days before the clashes, a Taliban commander backed a communal militia as they seized lands from Uzbeks in neighboring Sar-e Pol province. These events suggest that the Taliban’s policies around ethnic minorities may be causing tensions among Taliban factions themselves.

The highest number of reported fatalities resulting from a single event of Taliban infighting occurred along the Tajikistan border in January 2022 (Interfax.ru, 10 January 2022). The Tajik president has expressed concern over the presence of Taliban forces along the border, though the Taliban denies the fighting took place (Eurasianet, 14 January 2022). The Taliban government has complex relationships with neighboring countries Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, as both have hosted former government officials and military members who fled Afghanistan when the Taliban took over.

Lessons Learned: The Importance of Adaptive Information Collection

As a new period of Taliban governance begins, continued tracking of political disorder in Afghanistan will be reliant on reporting and sourcing that responds to evolving conditions on the ground. Failure to adapt one’s sourcing strategy when there is a considerable shift in the political environment (both in terms of conflict patterns and also press freedom) can lead to important trends being missed. As shown in this report, the adaptations made by ACLED and APW have allowed for a clearer picture to emerge of disorder patterns after the fall of Kabul. These trends would not have been captured otherwise and thus reflect an important lesson to be learned concerning data collection and analysis. As ACLED and APW continue to track political violence and protest trends in Afghanistan, the reliability of the data will be dependent on maintaining an approach to data collection that is responsive to the situation on the ground. As the press remains restricted, and journalists face violence for reporting, support for primary information collection efforts by local conflict observatories such as APW will be critical.