As India celebrated its 72nd Independence Day on 15 August 2018, the country continues to face multiple and complex challenges. Disorder—including political violence and protests—is increasingly multidimensional, complex, and evolving (OECD, 2016; United Nations & World Bank, 2018). Multiple types of disorder can co-occur across states, can interact, and may involve different agents as well as spatially distinct regions subnationally (Raleigh, 2014). This complexity can contribute to fragility as it can make it more difficult for a state, as well as the international community, to address so many interconnected and distinct issues simultaneously.

This varied arena of contestation is especially apparent in India in which a number of contestations co-occur. The Indian state engages with multiple agents simultaneously: with rebel forces in the Northeast; with a Maoist insurgency; with an international adversary in the Jammu & Kashmir region; as well as with its own constituency in the form of demonstrations across the country. Not all forms of disorder in India involve the state, however: inter-rebel conflict in the Northeast; communal conflicts, including inter-caste and inter-religious violence; and one-sided demonstrations. This varied landscape creates a complex environment within India—the nuance for which would be missed with aggregate measures of conflict.

I. Conflict in Jammu & Kashmir

There are several ongoing conflicts in India between state forces and non-state actors as well as against foreign state forces. Over 40% of all political violence events in India take place in the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). J&K has been the site of conflict since the accession of the former Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir to India in 1947. Following violent contestations between Pakistan and India, the previously-independent state eventually dissolved into the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) and the Pakistan-controlled territories of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) and Gilgit-Baltistan.

As the only majority Muslim state in Hindu-majority India, India’s control of J&K has long been a source of tension both internally and between India and Pakistan. This tension has manifested violently through sporadic outbreaks of cross-border violence between Indian and Pakistani forces, as well as the activities of militant groups fighting against the Indian state, such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), and Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM).

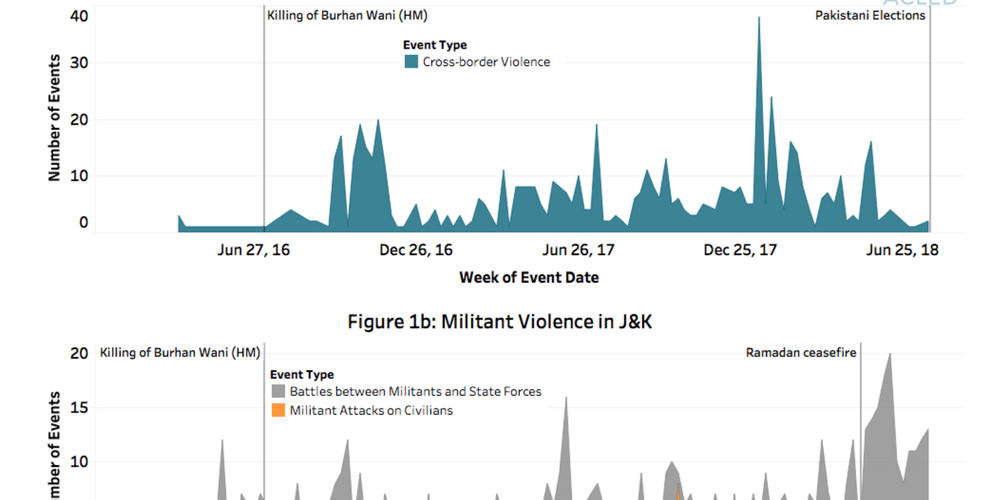

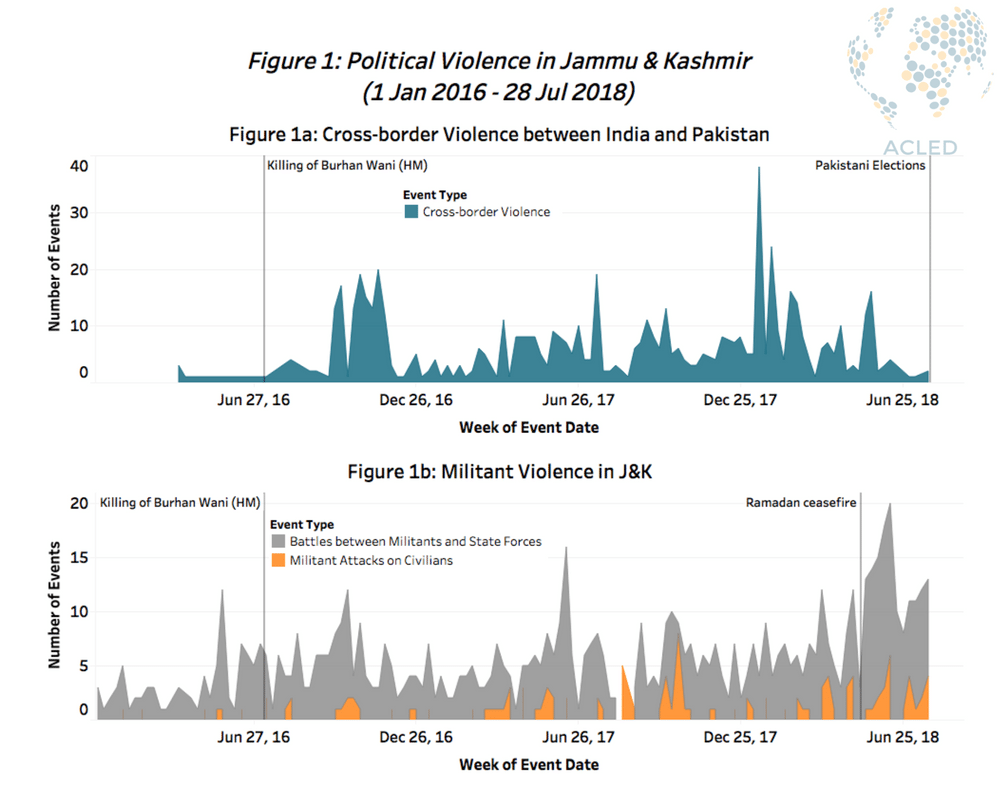

Though operating on different scales, these two aspects of conflict in the region often inform one another. After the killing of HM commander Burhan Wani by Indian forces on 8 July 2016, several successful militant attacks on Indian government forces led the Indian military to launch so-called “surgical strikes” on militant targets across the Line of Control (LoC) into Pakistan. These strikes led to a sustained period of increased cross-border activity between Indian and Pakistani forces that continued until the end of that year (see Figure 1a).

At the same time, these modes of political violence are also informed separately by internal politics in India and Pakistan. When the Indian central government instigated a unilateral Ramadan ceasefire in J&K on 16 May 2018, militant groups took the opportunity to step up their activities, resulting in an upsurge in militancy-related violence (see Figure 1b). Whilst the ceasefire has ended, this increased militant activity has continued in J&K (for more on this, see this recent ACLED piece).

Conversely, there was a significant reduction in cross-border violence between Indian and Pakistani forces in the period leading up to the July 2018 general elections in Pakistan (see Figure 1a). It is yet to be seen how – or if – the success of Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) at the polls will affect conflict in J&K. Past history, however, suggests that any drops in cross-border violence may be short-lived, as ceasefire violations between the two states are plentiful. Both cross-border and militant-related violence in J&K remains unpredictable and unlikely to disappear any time soon.

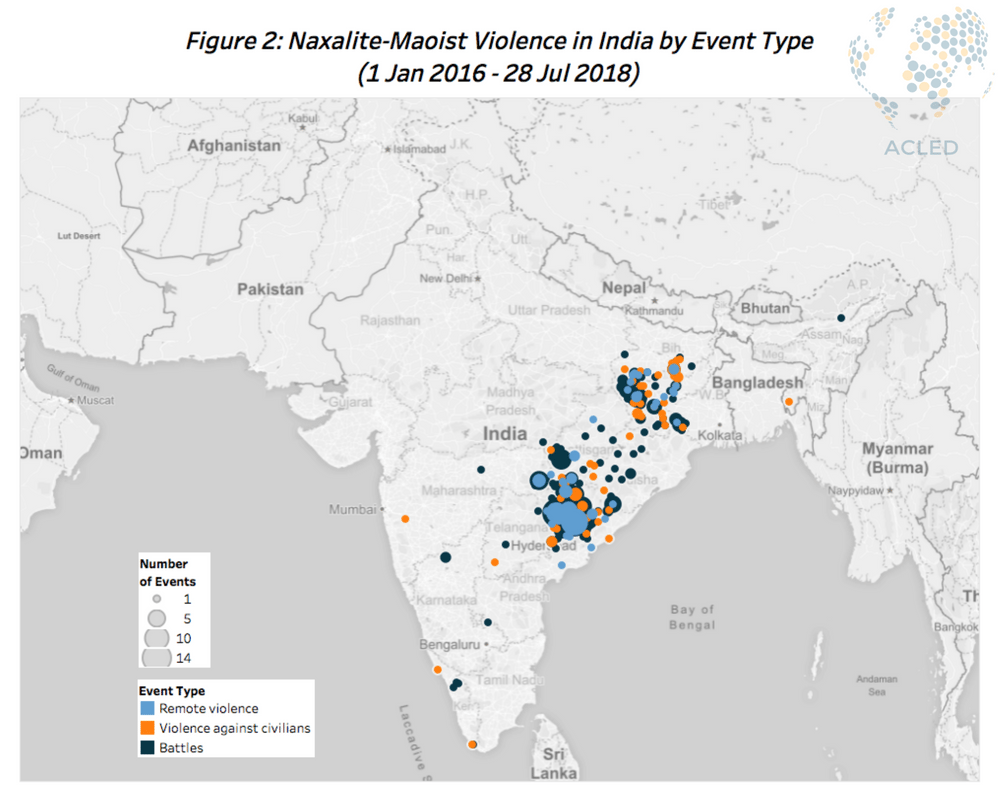

Contributing to about 29% of political violence in India is the Naxalite-Maoist insurgency in the so-called ‘Red Belt area’, which covers a vast territory in central, eastern, and southern India. The Maoist insurgency has its root in the socio-economic Naxalbari uprising from 1967 and was revived again in 2004 with the formation of the Communist Party of India (Maoist). What started as a resource war over agricultural landholdings has evolved into a fight over Maoist ideology and the legitimacy of the Indian state in the insurgency-affected area (The Diplomat, 21 Sept 2017).

Looking at the data from January 2016 to the end of July 2018, almost half of the reported conflict events involving Maoist rebels took place in the state of Chhattisgarh, followed by Jharkhand, Odisha and Bihar (see Figure 2). Over half of the reported conflict events are battles, followed by violence against civilians and remote violence (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece).

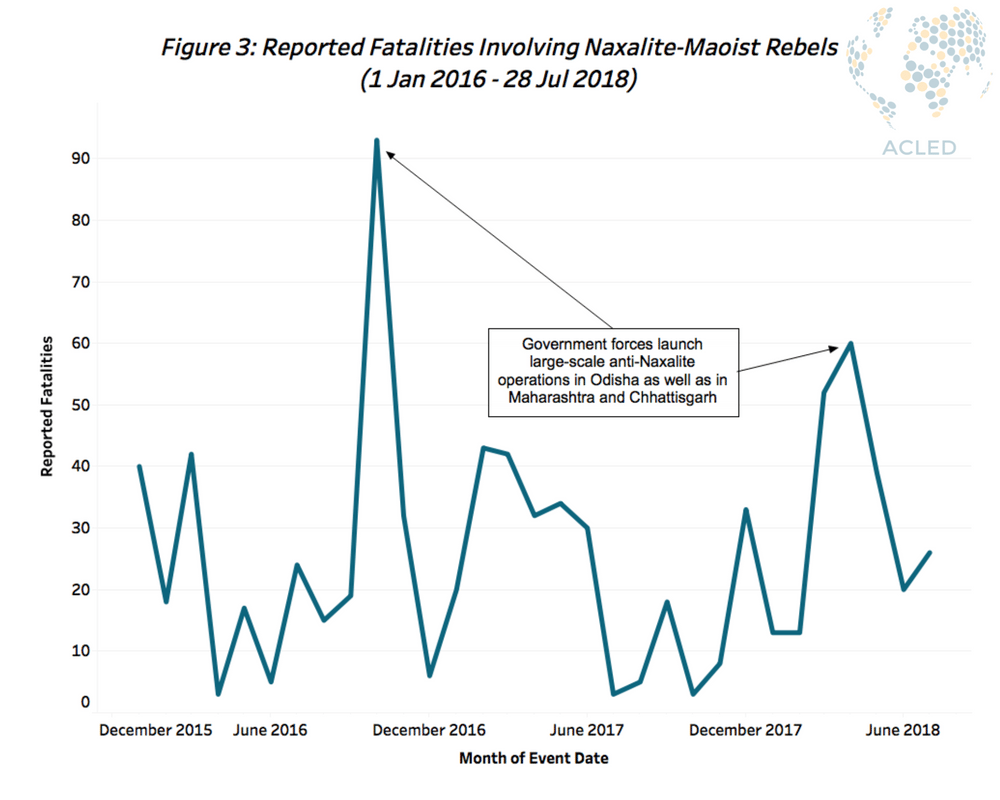

Violence in connection with the Maoist insurgency has been steadily decreasing since 2010 (Encyclopedia Geopolitica, 2018). Since 2016, the Indian government reports a significant reduction in violent incidents and civilian deaths while the numbers for Maoist casualties and surrenders increased for those years compared to the years prior to 2016 (OneIndia, 16 Aug 2018). ACLED data for 2016 to July 2018 show two major spikes in the numbers of reported fatalities stemming from Maoist-related violence—in October 2016 and April 2018 — when government forces launched large-scale anti-Naxalite operations in Odisha as well as in Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh (see Figure 3).

The violent conflict between Naxalite-Maoist rebels and Indian state forces has been a longstanding factor contributing to the complex and multidimensional nature of political violence in the country. While the lethality of the conflict has decreased over the past decade, recent numbers from 2016 to 2018 show that levels of political violence remain constant and show no sign of abating. An end to the Naxal-Maoist insurgency is, therefore, not in sight.

III. Violence in Northeast India

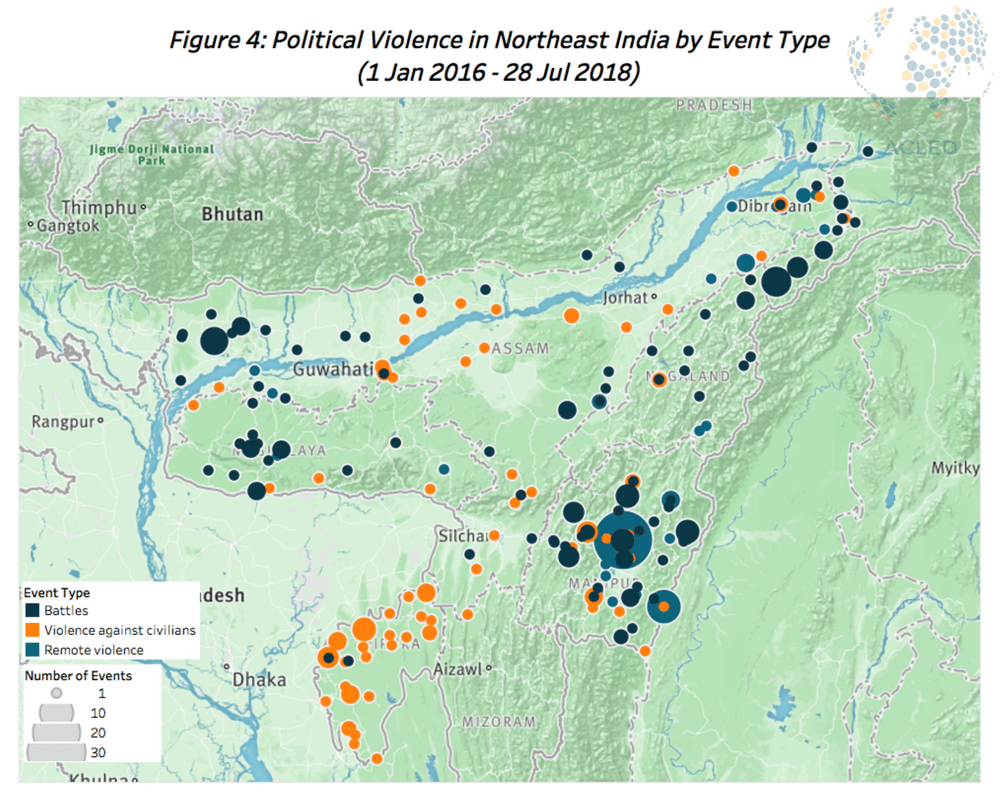

Contributing to about 12% of the overall political violence in India is violence in Northeast India. The Indian state has been dealing with insurgent groups in the Northeast since 1950, soon after its independence. The region is comprised of seven states—Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura—each with specific cultural characteristics and a variety of tribal communities. This ethnic diversity—and its geographical and cultural distance from the rest of the country—has led to the emergence of a large number of armed groups that demand independence or a substantial level of autonomy.

In previous decades, the insurgency in the Northeast has become less violent due to the imposition of various Armed Forces Special Power Acts (currently in force in Assam, Nagaland, and Manipur; see The Morung Express, 13 August 2018) and the negotiation of agreements and ceasefires between the rebel groups and the government (such as the Naga Framework Agreement, signed in 2015; see The Hindu, 18 July 2018). However, there are still varying degrees of insurgency in most states, such as episodes of remote violence, as well as growing protest movements by their population (see Figure 4).

In 2018, more than 20 battles were reported between Indian Security Forces and rebel groups, with the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Isak-Muivah (NSCN-IM) being the most active non-state actor. Although direct battles have become less frequent, there are constant reports of killings by state forces in so-called “fake encounters”. In Manipur, the Indian Army, the Assam Rifles, and the Manipur Police are being investigated in 1,528 cases of extrajudicial killings from 2000 to 2012 (The Indian Express, 2018). In August 2018, protests were held by local communities to demand justice for those killed in such instances, which included a member of the rebel group People’s Liberation Army of Manipur (PLA) (Imphal Free Press, 2018).

IV. Demonstrations

Besides militant insurgencies, India faces various other challenges like poverty, gender inequality, minority rights, and a rural-urban divide, to only name a few. The most common manifestations of these challenges are demonstrations, which make up 90% of all reported events in India. Protest demonstrations are most commonly concerned with labour rights, law and order, political or legislative issues, as well as lacking development. Certain trigger events—such as the flogging of Dalit men in Una in July 2016, or the government’s demonetization policy in November 2016—as well social issues—such as violence against women, farmers’ issues, and reservations for minorities—periodically lead to state- or nation-wide protest movements. In analyzing the demonstrations by the type of group demonstrating, the three most active groups are political parties, labour groups, and students (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece).

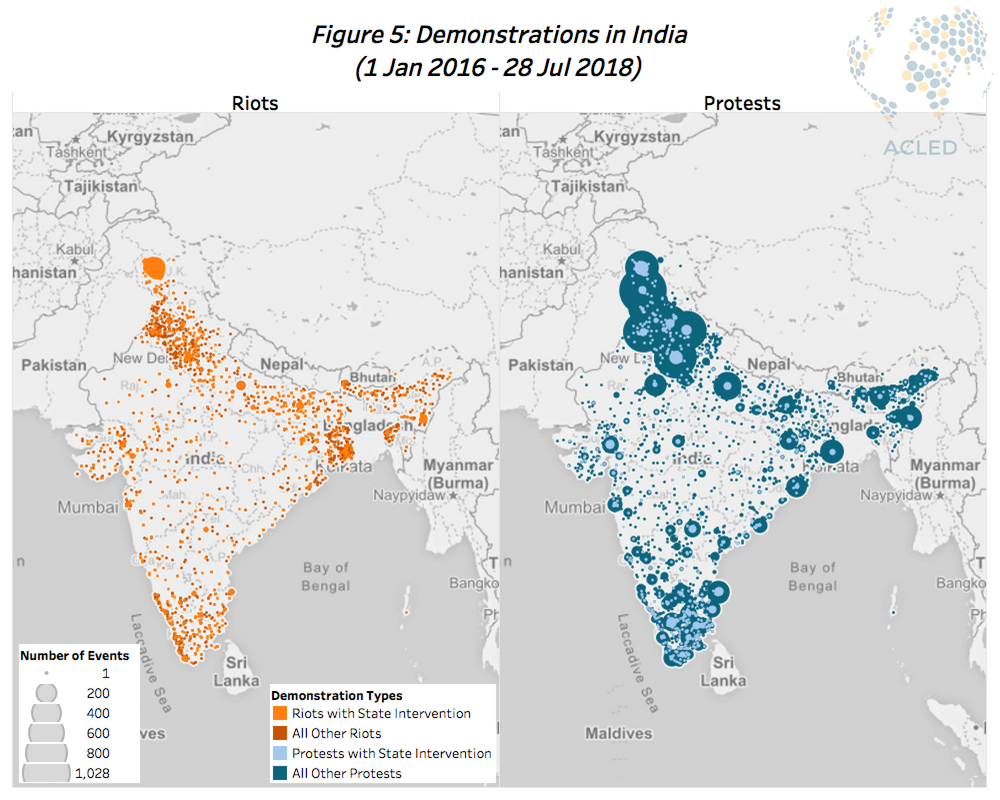

Looking at ACLED data for 2016 through July 2018, the highest number of demonstrations—over 50%—occur in North India, one-third occur in South India, and the remainder in East India. The majority of the demonstrations in India each month are peaceful, with only about 1 in 5 resulting in violence. Demonstrations that take place during election cycles have greater potential for escalating into violence (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece).

Whether state forces get involved in demonstrations varies on a number of factors, including the scale of the demonstration and the effect on public services and general law and order (see Figure 5). The number of violent demonstrations involving government forces only account for around 9% of all demonstrations. The notable exception to typically non-violent demonstrations in India is in the state of J&K where demonstrations frequently turn violent with state forces engaging rioting locals.

V. Communal, Caste, and Identity-Based Violence

Not all disorder in India involves the state. For example, within the conflict landscape of the Northeast, while state forces engage with rebels, there is also inter-rebel conflict, highlighting the multidimensionality of the violence in the region. In Nagaland, the intra-ethnic rivalry among the Naga tribes contributes to the presence of distinct and competing armed groups. For example, in May 2018, a civilian and two militants were killed during a clash between two factions of the Nationalist Socialist Council of Nagaland—the Isak-Muivah and the Unification factions (India Blooms News Service, 2018).

Several political and tribal groups have demanded the departure of millions of Bengali-speaking minorities—mostly Muslims—who have crossed the porous border with Bangladesh and settled in the region since the 1950s. In Assam, the National Register of Citizens (NRC) recent draft, released on July 30, left out more than 4 million residents who could be declared ‘illegal immigrants’. Indigenous communities in other states in the Northeast are also calling for a similar register to curb the presence of non-tribal people (The Telegraph India, 2018). The increased nationalism and discrimination against the non-tribal population, often voiced in protests and riots, could further escalate to episodes of communal and ethnic violence, changing the landscape and the dynamics of conflict in the region.

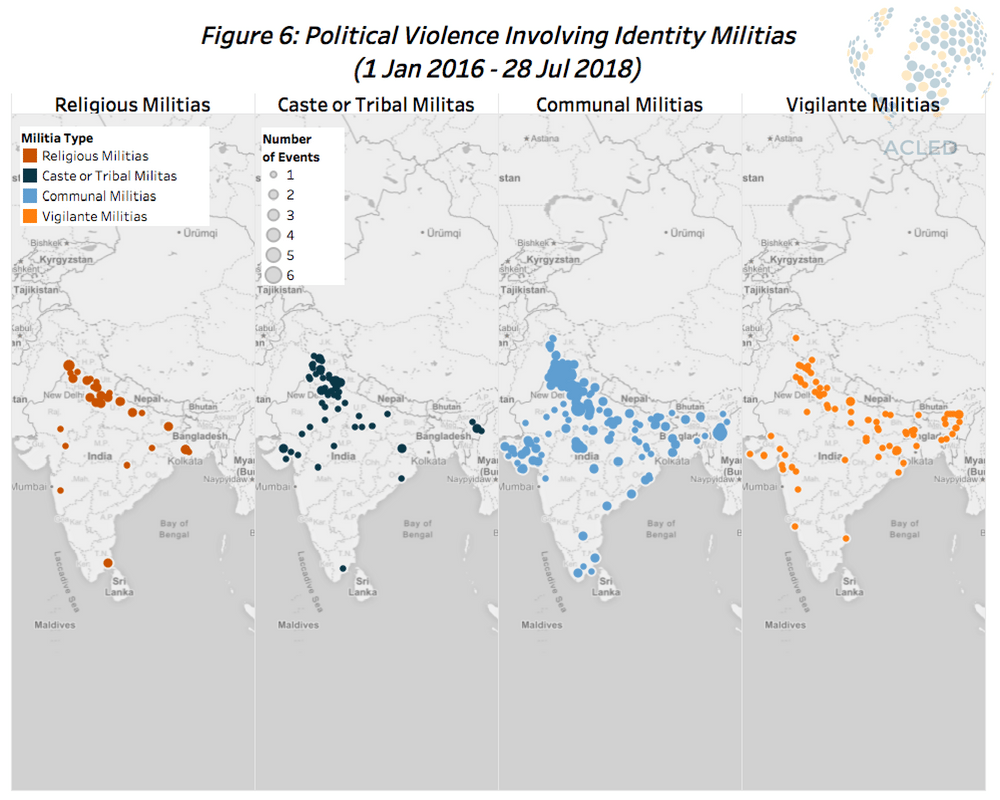

India has a long history of communal faultlines often dating back centuries. The most visible divides are religious, between Hindus and Muslims, and inter-caste, especially between upper-caste Hindus and Dalits. Inter-religious and inter-caste tensions have led to communal violence in the past (see Figure 6).

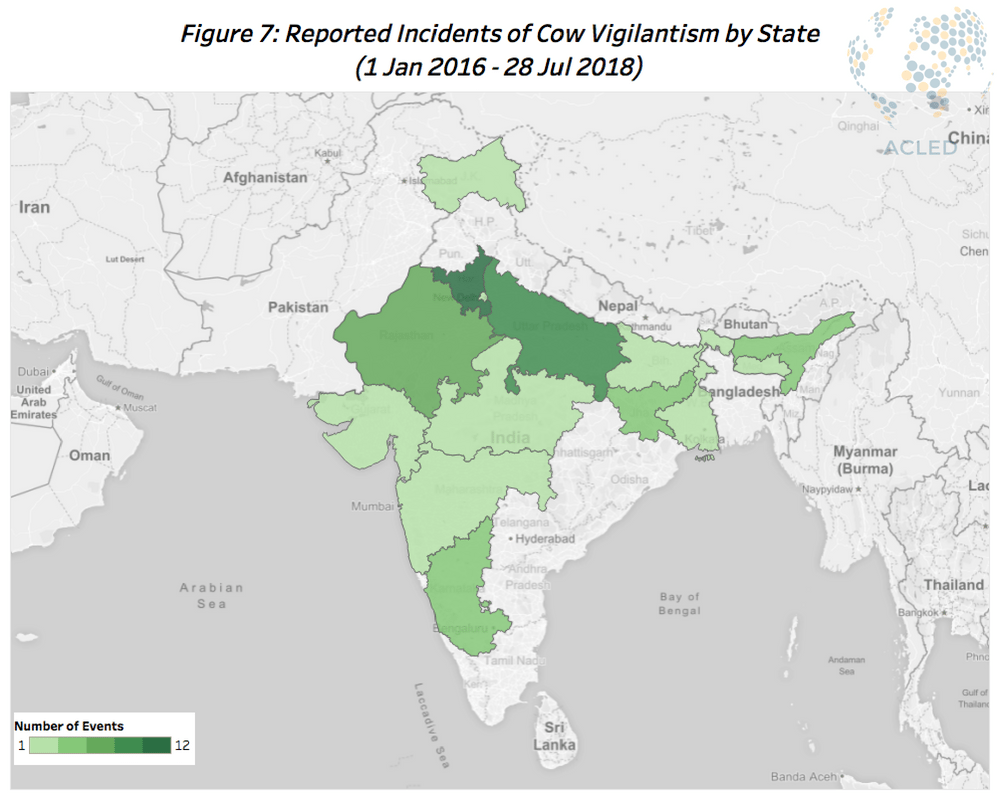

However, since Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) —which embraces the Hindu nationalist Hindutva ideology—came to power in May 2014, a steep increase in communal violence has been recorded in national-level violence (The Telegraph, 15 August 2018). The most visible manifestation of this has been the increasing incidents of cow vigilante violence typically directed towards Muslims and—to a lower extent—Dalits. According to IndiaSpend, the vast majority of cow vigilante attacks between 2010 and 2017 have been reported post-May 2014 and in states governed by BJP, pointing to the link between the rise of Hindutva and this form of vigilantism (IndiaSpend, 28 June 2017; see Figure 7).

With rising population and limited access to land and other resources, especially water, communal violence in India is often also the result of conflict over livelihoods in groups seeking to gain access to necessary resources—a result of resource management by the state (see Figure 6). In addition, there has been an increasing number of public lynchings by locals taking law into their own hands in recent years. Especially in summer 2018, a high number of mob lynchings based on disinformation about ‘child lifting’ through fake news and social media platforms were reported across India. The increasing number of events involving vigilante violence against presumed criminals is indicative of the perceived lack of law enforcement and lack of trust in India’s criminal justice systems (see Figure 6).

Conflict datasets must correspond to the dynamics of conflict today if they are to capture the shifts and nuances in disorder. “[In datasets] where conflicts are coded as full campaigns of violence that can last years, it can be difficult to capture these shifts and nuances accurately—resulting in a much simpler view of a very complex context” (United Nations & World Bank, 2018). In cases too where conflicts are viewed at the national-level and are framed as purely dyadic, important subnational variation and complexity is missed—especially as “states and societies can experience multiple forms of violence simultaneously, each caused by related issues but with different locations, triggers and impacts on fragility” (OECD, 2016). The Indian case here illuminates the importance of allowing for such analysis.

AnalysisAsiaCivilians At RiskEthnic MilitiasFocus On MilitiasInequalityPolitical StabilityPovertyPro-Government MilitiasRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsVigilante MilitiasViolence Against Civilians