The addition of identity types to ACLED data on political violence targeting women sheds new light on the physical threats to women’s participation in political processes, such as running for or holding office, supporting or voting for political candidates, leading human rights campaigns or civil society initiatives, and more. This report analyzes the expanded data to unpack key trends in violence targeting women in politics. Download the expanded data and read the updated Political Violence Targeting Women FAQs for more information about ACLED methodology.

Introduction

Three years ago, in partnership with the Strauss Center for International Security and Law, ACLED released new data capturing political violence targeting women (PVTW), revealing the many types and perpetrators of politically motivated attacks on women across all regions of ACLED coverage.1At the time, this included Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. Building on that work, ACLED has now expanded the data — reviewing over 11,000 PVTW events around the world — to introduce identity types for the targets of PVTW, including further detail that specifically enables the tracking of political violence targeting women in politics (PVTWIP) for the first time. This report, released during the UN’s 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence following the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women and International Women Human Rights Defenders Day, analyzes the expanded data and sheds new light on the threats against women participating in political processes, such as running for or holding office, supporting or voting for political candidates, and more.

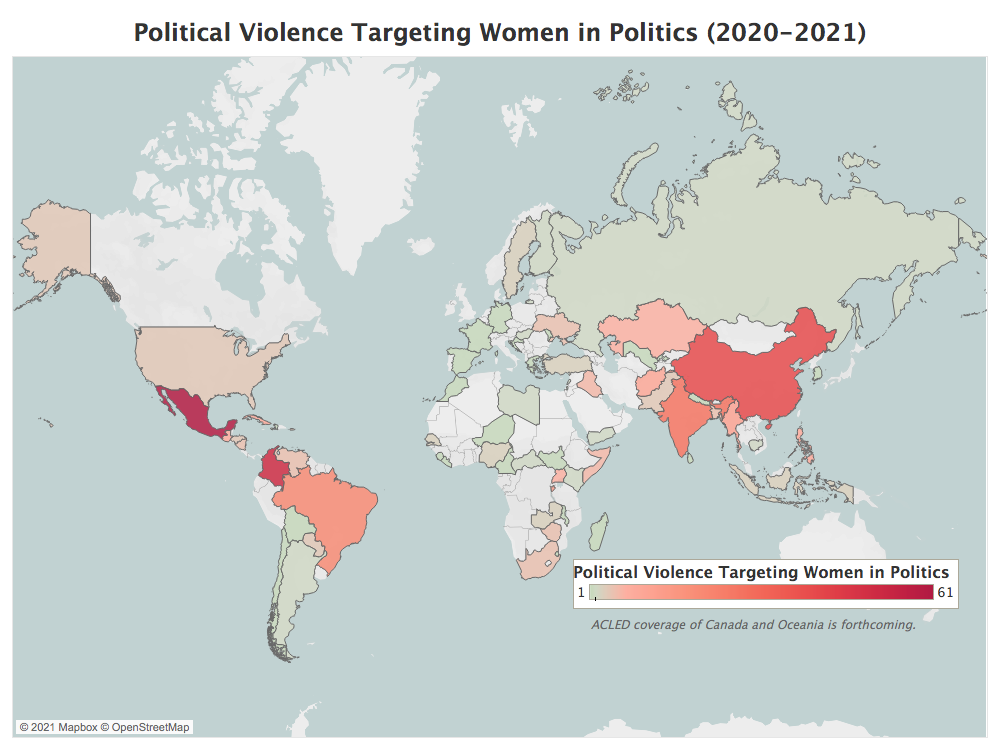

Unprecedented numbers of women have engaged in elections in recent years, both by seeking office (Foreign Policy, 7 August 2017; France24, 1 October 2021) and by voting (CEIP, 8 November 2018), setting new records in countries around the world. With these accomplishments, however, they have faced heightened risks of violence. These new data provide a clearer picture of the range of different physical threats women are subjected to as they engage in political processes. Our analysis finds that PVTWIP in particular has increased over time in nearly all regions of ACLED coverage, including in Africa, Central Asia and the Caucasus, Europe,2This trend pertains to European countries for which ACLED coverage extends back to 2018; European countries for which coverage begins in 2020 do not yet have multiple years of data to allow for such comparisons. See our current list of country and time period coverage here. Latin America, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.3This includes countries for which ACLED coverage started prior to 2020 so that annual comparisons could be made. Since 2020, some of the most violent countries for women in politics include Mexico, Colombia, China, India, Brazil, Burundi, Myanmar, Afghanistan, the Philippines, and Cuba.4This is based on analysis of PVTWIP trends since 2020 to allow for fair comparisons across all regions, as ACLED has uniform coverage of all regions for 2020 to present. See our current list of country and time period coverage here.

In addition, this report extends ACLED’s original analysis of PVTW trends to new regions that were not previously covered in the dataset, including East Asia, Central Asia and the Caucasus, Latin America, Europe, and the United States.5ACLED coverage of Canada and Oceania is forthcoming. The data show that PVTW more largely has continued to rise in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, and that such violence is also on the rise elsewhere, such as in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Even in regions where PVTW has not increased on aggregate, such as in Latin America, the threats posed by specific perpetrators and the threats faced by specific groups of women have intensified — such as spikes in attacks on women candidates during the 2020 municipal elections in Brazil. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for identifying programs, policies, and strategies to effectively combat the full spectrum of threats — many of which are local and context-specific — in order to better facilitate and safeguard women’s political participation around the world.

What Is PVTW?

‘Political violence targeting women’ (PVTW) captures political violence in which women or girls are specifically targeted6Cases where the main victim(s) in the event is composed entirely of women/girls, majority women/girls, or if the primary target was a woman/girl (e.g. a female politician attacked alongside two male bodyguards) are categorized as PVTW. — not all cases in which women or girls are affected or impacted by political violence.7Such cases of targeting are deduced by who the victim(s) of such violence are. As ACLED is an event-based dataset, each PVTW event can involve one to many victims.Each entry in the dataset is an ‘event’. Events are denoted by the involvement of designated actors, occurring in a specific named location and on a specific day. For example, three women killed by a soldier in a specific town on a certain day is collected as a single event; a girls’ school attacked in a specific town on a certain day is coded the same way. The number of events should therefore not be conflated with the number of victims. This means that PVTW does not capture the entirety of violence faced by women and girls, as it is not a gender disaggregation of all political violence. Rather, it specifically captures cases in which a woman’s gender is the salient identity for which she is targeted.8Events in which women or girls are killed alongside men or boys, for example, are not categorized as PVTW (e.g. an airstrike being dropped on a town will likely kill both women and men; the women in this case were not specifically targeted in such violence). Accordingly, ACLED tracks PVTW which targets women in politics (e.g. candidates, politicians, political party supporters, voters, etc.), as well as other women from all walks of life, regardless of their occupation or direct engagement in politics.9These data are publicly available for download, updated on a weekly basis.

It is important to remember that the trends captured by ACLED pertain only to political violence in the public sphere that targets women, not all violence against women, which is a much wider category that includes domestic, interpersonal, and criminal violence. ACLED also only captures physical violence.10“Physical violence is the most universally recognized as ‘violence’. Violence is defined as ‘the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy’ (Merriam-Webster, 2020). International humanitarian law recognizes the physical endangerment of civilians as a war crime. Outside of war, physical abuse of another tends to come with legal ramifications. [ACLED tracks] physical manifestations of political violence targeting women. This subset of violations that women face is positioned on the physical side of the continuum of violence … In the field of conflict studies and studies of political violence, the word ‘violence’ tends to specifically distinguish physical manifestations of violence. Other types of violations that women may face — including threats and intimidation — are recognized as negative factors that have negative ramifications for women’s involvement in political processes, yet tend to not be labeled as ‘violence’. Other forms of violations that women face, such as threats, intimidation, or bullying, are not explored [by ACLED] — all of which are incredibly more prevalent than physical violence. Yet a focus on physical violence here captures the most immediately life-threatening violations. Impunity for perpetrators of physical political violence targeting women is high, despite the fact that such crimes are legally enforceable” (Kishi, forthcoming). Additionally, violence targeting women can be underreported for a variety of reasons, meaning ACLED data represent a conservative estimate of the full scale of PVTW11“It is important to note that underreporting of violence targeting women by victims is common due to … normative concerns and this should be considered when drawing conclusions from the data. As is the same for all datasets, coverage within the ACLED dataset is limited to what has been reported in some capacity” (ACLED, 2019). No dataset is able to reflect the Truth (with a capital T); this is important to consider when reviewing trends from any data source. ACLED makes every attempt to accurately and thoroughly capture political violence through various sources of reporting including traditional media, new media, reports by international organizations, and information gathered by local partners. (for more on the structure of these data, see ACLED’s FAQs on how to work with the PVTW data subset).

‘Political violence targeting women in politics’ (PVTWIP) in turn refers to PVTW that targets a specific subset of women: those engaged in politics. These categories of women, and trends in such violence, are explored in the following section.

Target Identities of PVTWIP12The trends explored here represent various time periods across different regions, reflecting ACLED’s varied temporal coverage of countries. This coverage can be found in this table. Comparisons of proportional rates of variables such as targets, types, or perpetrators of violence — which is what is explored across all of the tables presented in this report — is also less impacted by differences in temporal coverage.

This report introduces the identity types of women targeted by PVTWIP, outlined in the table.13These categories of women are stylized as a ‘tag’ in the Notes column of ACLED data (e.g. “[women targeted: politician]”). This information is included for all PVTW events (i.e. where “Women (Country)” is coded as an Associated Actor to “Civilians (Country)”). As multiple women may be targeted in a single ACLED event, more than one identity category may be applicable, and hence included, per event. In such cases, multiple tags may appear in the notes (e.g. “[women targeted: politician][women targeted: voter]”). (For more on the structure of these data, see ACLED’s FAQs regarding how to work with the PVTW data subset.) These identity types include women candidates for office; politicians; political party supporters; voters; government officials; and activists, human rights defenders (HRDs), and social leaders.14These categories of women in politics are in line with those used by others examining ‘violence against women in elections’ (NDI, 2016). As multiple women may be targeted in a single ACLED event, more than one identity category may be applicable to a single event.15This means that analysis using such categorizations is actor-based rather than event-based.

| Type of Target | Definition | Example | % of Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate for Office | A woman who is running in an election to hold a publicly elected government position; that position can be in local, regional, or national government. This includes, but is not limited to, incumbent candidates. | A female candidate from the Mon Unity Party (MUP) was shot and killed by an unidentified gunman in the evening near Payathonzu town in Myanmar. | 8% |

| Politician | A woman who currently serves in an elected position in government, regardless of whether that government is at the local, regional, or national level. | Mortar fireworks were fired at the balcony of a woman politician’s parents in Corbeil-Essonnes in France while she was having dinner inside with several members of her family, likely triggered by political disagreements. | 12% |

| Political Party Supporter | A woman who contributes to, endorses, and/or acts in support of a political party or candidate that extends outside of voting, via membership, participation in party events, monetary donations, or other forms of support. This also includes women who refuse to act, endorse, or support a specific political party or candidate, regardless of whether or not their preferred party or candidate is listed. | Two women, allegedly members of the Citizens’ Movement (MC) party who were caught buying votes, were beaten by a group of people in Fraccionamiento Los Mangos in Mexico. | 24% |

| Voter | A woman who is actively participating in, has actively participated in, or attempts to actively participate in local, state/regional, and/or national elections or referendums. Active participation here refers specifically to registering to vote or casting a ballot in an election. | A Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M) woman voter was attacked by suspected Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporters in Matabari area in India after the results of the Parliamentary elections were released. | 2% |

| Government Official | A woman who works for the local, regional, or national government in a non-partisan capacity. This includes public/civil servants, local authorities, or non-partisan political appointments, such as judges. This also includes women who work to support the proper functioning of elections; electoral assistance groups include independent and/or non-partisan poll workers or poll monitors. | A group of locals beat up and injured a woman judge in Soavinandriana in Madagascar over a family court case. | 16% |

| Activist/ Human Rights Defender/ Social Leader |

A woman who peacefully advocates for a specific social cause and/or actively promotes the expansion or protection of human rights. These rights can include women’s rights, civic rights, environmental rights, and more. This also includes social leaders, who are often prominent, local activists known for their community advocacy. | An Iraqi activist was kidnapped by unidentified men on her way to Tahrir square in Baghdad in Iraq, though was later released. | 38% |

Again, it is important to remember that these data capture physical violence specifically. This means that this violence represents a subset of all “violence against women in politics” (VAWIP) as defined by others, often presented as comprised of “five forms of violence”: physical, sexual, psychological, economic, and symbolic (see for example, Krook, 2017). In such an interpretation, violence is defined as a “violence of integrity … any act that harms a person’s autonomy, dignity, self-determination and value as a human being” (The Conversation, 21 October 2020). The violence captured by ACLED data and explored in this report, however, differs from this definition. When considering the common categorization of ‘five forms of violence’, the definition of ‘political violence targeting women in politics’ used in this report looks specifically at a subset of physical violence — that which occurs in the public sphere, hence excluding domestic abuse — and a subset of sexual violence — rape, outside of that which occurs within interpersonal relationships, and excluding sexual harassment alone.

Such physical violence makes up a small proportion of the threats faced by women participating in political processes, with physical violence less common than non-physical forms of intimidation, like harassment or online abuse, which can be aimed at undermining women’s engagement (Krook and Restrepo Sanin, 2019). For example, a local election monitoring group that observed the 2015 national elections in Guatemala, focusing on electoral violence against women and other vulnerable communities, found that in the lead up to the election, only 3% of reported incidents of intimidation were physical in nature (Votes Without Violence, 2018). Similarly, in Nicaragua — one of the most gender-equal countries in the world with respect to women’s representation in parliament — a local organization conducted a non-partisan independent observation throughout the 2016 election period, tracking reports of violence against women during the election; they found that of all confirmed critical incidents reported by observers, only 2% of incidents took the form of physical violence (Votes Without Violence, 2018). Nevertheless, physical violence targeting women comprises an important subset of the threats that women, especially those in politics, may face as it is the most deadly.

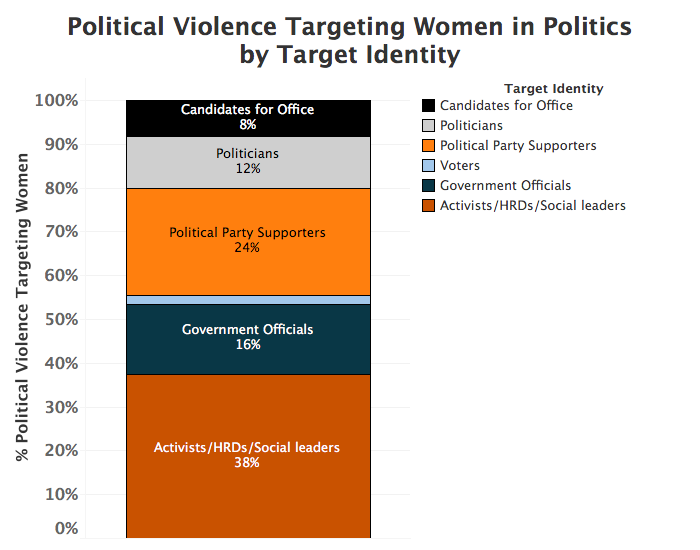

Women engaged in various parts of the political process face different risks of violence (see graph), and this risk too varies over time. Specifically, such risk are typically heightened during election periods — often referred to as “violence against women in elections” (VAWE) (Votes Without Violence, 2018). This violence is considered a threat to the integrity of elections, as a subset of the population is systematically excluded or blocked from participation (NDI, 2016; IFES, 2021).

On the aggregate, 8% of the targets of PVTWIP are women candidates for office (in black in graph). For example, on 10 June 2018, an Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) woman candidate to the post of councillor in Quintana Roo was shot and killed by two men in Isla Mujeres, Mexico (El Universal, 12 June 2018). Beyond physical violence captured by ACLED data, “female participants in politics are disproportionately targeted online as well, where they confront an onslaught of harassment on social media. … [as well as] widespread harassment of female candidates, often at the hands of party leaders, police officers, or election administrators” (Foreign Affairs, 2019). “Whereas abuse against men in politics largely relates to their professional duties, the online harassment of female candidates is far more likely to include comments about their physical appearance or threats of sexual assault” (Foreign Affairs, 2019).

Similarly, on the aggregate, 12% of the targets of PVTWIP are women politicians (in gray in graph). For example, on 9 August 2019, a barangay chairwoman was killed in a vigilante-style attack by unidentified motorcycle-riding assailants in Metro Manila, after having been tagged by the president as a ‘narco-politician’ before the elections (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 10 August 2019). Again, in addition to physical violence, women politicians also face other non-physical abuse, such as death threats or harassment (The Conversation, 21 October 2020). For example, a study by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) found that nearly 82% of women members of parliament surveyed from around the world experienced some form of psychological intimidation, with nearly half of them having received “threats of death, rape, beatings or abduction during their parliamentary terms, including threats to kidnap or kill their children” (IPU, 26 October 2016).

On the aggregate, nearly a quarter — 24% — of the targets of PVTWIP are women political party supporters (in orange in graph), making them one of the categories at highest risk of violence. For example, on 20 September 2021, in Myoma Botae ward of Sagaing region, Myanmar, a woman party campaigner for the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) was shot and killed by unknown gunmen (DVB, 20 September 2021). Women political party members and supporters can face violence both externally, from those opposed to who they support, as well as from within their own political party. And again, as with candidates and politicians, these women face harassment, discrimination, and psychological abuse, both in person and online, in addition to physical violence. “Both men and women experience [such] negative behaviors that are often dismissed as ‘the cost of doing politics,’ but these behaviors have different dynamics according to gender,” underscoring the importance of capturing different forms of gendered targeting (NDI, 19 March 2018).

Two percent of the targets of PVTWIP are women voters (in blue in graph). This captures physical violence targeting women for actively participating in voting, such as registering to vote or for having cast a ballot. For example, on 14 January 2019, militants either from the Nduma Defence of Congo (Renové) (NDC-R) or the Alliance of Patriots for a Free and Sovereign Congo (APCLS) attacked a village in Masisi, DRC, killing at least 10 people and raping at least two women, accusing the residents of having voted for the wrong candidates (UN Human Rights Council, 6 March 2019). While women voters comprise a smaller percentage of the targets of PVTWIP, this may be because women voters more often face other forms of intimidation. For example, a local civil society organization that monitored Tanzania’s 2015 general elections — which were “some of the closest since the country’s transition to multiparty democracy in 1992” — and tracked incidents of violence against women voters specifically, found that of the reported incidents of violence against women voters entering or exiting the polling stations, nearly two-thirds were acts of harassment, while physical violence was reported less frequently — one-quarter of the time (Votes Without Violence, 2018). Nevertheless, others have found that physical violence against women voters — as well as harassment and psychological abuse — has been increasing around the world during elections (Fair Observer, 31 October 2018).

On the aggregate, 16% of the targets of PVTWIP are women government officials (in navy in graph); this includes public and civil servants, local authorities, and non-partisan political appointments, among others. For example, on 11 January 2019, unidentified armed men shot dead a woman assistant district public prosecutor in Hafizabad city, Pakistan (The Nation, 12 January 2019).Targeted attacks against such women negatively impact the role that they can play in effective governance and development in their country (UN Women, 16 September 2013). During election periods, women serving in electoral assistance groups, or as poll workers or monitors, can also be targeted. In addition to physical violence, intimidation and threats, both in the public as well as the private sphere, can be even more common. For example, a woman poll worker might face intimidation by political party supporters who demand she stuff a ballot box or risk physical harm, as well as intimidation from her husband demanding she stuff a ballot box or risk divorce and all of the societal repercussions that could result therefrom (IFES, 27 September 2017).

At 38%, the largest proportion of targets of PVTWIP are women activists, HRDs, and social leaders (in brown in graph). For example, on 25 September 2018, masked gunmen shot dead a human rights activist who had been involved in organizing protests demanding better services in the city; she was killed outside of a supermarket in Basra, Iraq (BBC, 25 September 2018). Such women have increasingly come under a range of different types of attacks, including legal attacks to hinder their human rights work, economic and structural discrimination, sexual violence, defamation, and intimidation (UN, 28 November 2018; Amnesty International, 29 November 2019). In addition to these risks, physical violence against their person also plays a role, exemplified by the prevalence of such women in politics being targeted relative to other women in politics. These risks can hinder women’s public and political participation (Newlines Institute, 1 July 2021).

Target Identities of PVTWIP by Region

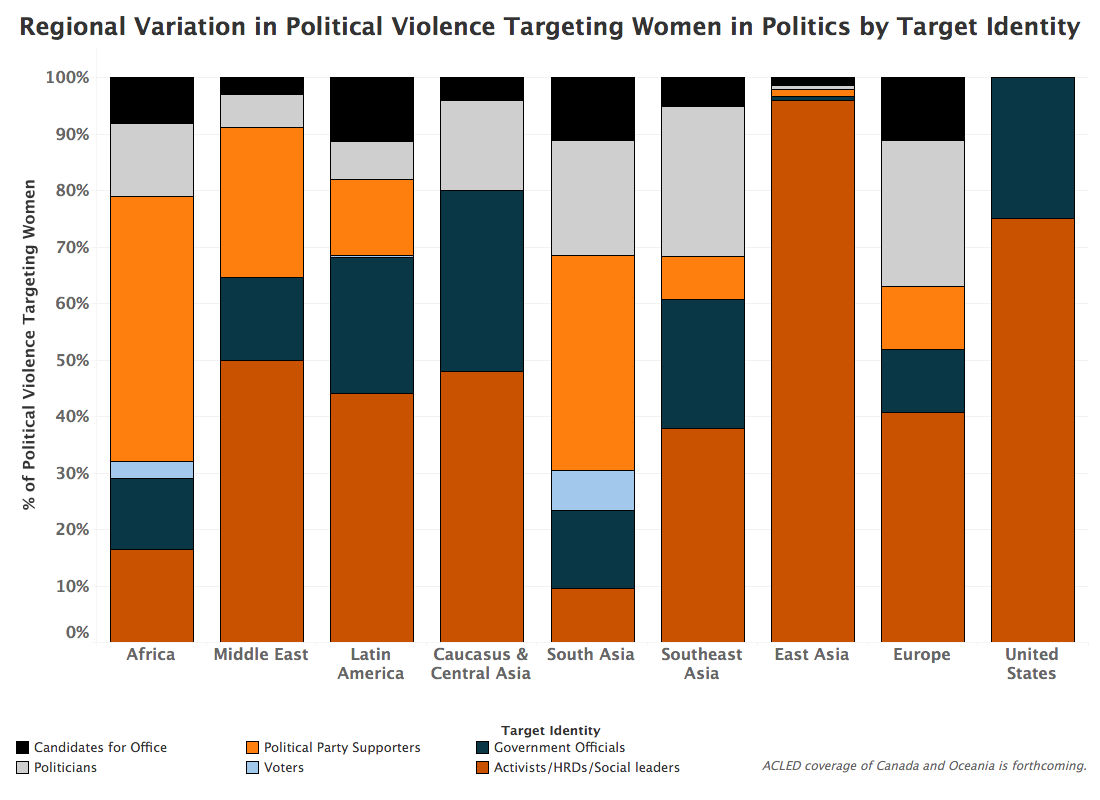

While the trends explored above hold when looking across both space and time, there is variance in which categories of women in politics are targeted across different regions (see graph below) — and even within regions, target trends can vary both across specific countries as well as over time, with heightened risks for certain categories during election periods, for example.

Around the world, 8% of the targets of PVTWIP are women candidates for office (in black in graph), yet these women make up over 11% of the targets of PVTWIP in Latin America (UN Women, 14 November 2018; Krook & Restrepo Sanin, 2016), in South Asia (UN Women, 2021), and in Europe. In Latin America, over half of these cases have taken place in Mexico, while over a quarter have taken place in Brazil. For example, on 26 May 2021, in Tocuaro, Guanajuato, in Mexico, the woman candidate for local deputy for the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM) in District 22 was attacked by armed men, who were shooting while she was holding a rally (Zona Franca, 26 May 2021; Jornada, 27 May 2021; SDP Noticias, 27 May 2021). In South Asia, over half of these cases have occurred in Bangladesh. For example, on 24 December 2018, a group of Bangladesh Awami League men attacked Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) candidate Yasmin Chhobi and her supporters while she campaigned in the Tebaria area of Natore town (The Daily Observer, 25 December 2018). In Europe, two-thirds have taken place in Greece. For example, on 18 May 2019, unidentified assailants targeted the private law office of a New Democracy woman political candidate (Tovima, 18 May 2019).

Women politicians (in gray in graph) face disproportionate risk in Europe and South Asia, where they make up 26% and 20% of the targets of PVTWIP, respectively — considerably higher than the global rate of 12%. In Europe, over 28% of these cases have taken place in Sweden and in Moldova, together accounting for over half of such targeting in Europe. For example, in early July 2020, a council woman was severely beaten, causing leg and arm injuries, in Musteata, Moldova (Jurnal, 22 July 2020). In South Asia, women politicians face greatest risk in India, which is home to nearly two-thirds of all such targeting in the region. For example, on 15 August 2021, in Sabroom in Tripura, India, around 200 people, allegedly including BJP members, surrounded and attacked two Trinamool women members of parliament, severely injuring one, and vandalized their cars (Tripura Chronicle, 15 August 2021).

Nearly a quarter of all PVTWIP targets women political party supporters (in orange in graph), yet in Africa and South Asia the risk to these women is even higher. In Africa, nearly half (47%) of all PVTWIP is against political party supporters, with Burundi and Zimbabwe disproportionately represented (home to 32% and 28% of all such targeting on the continent, respectively). For example, Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) youths attacked two women supporters of the Movement for Democratic Change (Tsvangirai Faction) (MDC-T) with iron bars because they were wearing MDC-T shirts in Epworth, Zimbabwe on 17 August 2017.16This event is sourced from one of ACLED’s local partners. In South Asia, over two-thirds (68%) of such targeting takes place in India. For example, on 22 July 2021, a group of BJP members allegedly attacked members of the women’s wing of the Trinamool Congress Party (TMC) on the outskirts of Cooch Behar town, injuring two of the women (The Telegraph, 23 July 2021).

Again, a similar regional trend holds for the targeting of women voters (in blue in graph). Around the world, 2% of all PVTWIP targets voters, yet this rate is higher in South Asia (7%) and in Africa (3%). In South Asia, India is again disproportionately represented, home to over half (57%) of all such targeting. For example, on 17 November 2018, a woman voter was hospitalized when a sarpanch17A sarpanch is the head of a panchayat, which is the local government system in India. candidate assaulted her during polling in the Gambhir village area in Jammu and Kashmir (Daily Excelsior, 18 November 2018). In Africa, women voters in Burundi again face heightened risk, as well as women voters in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); over 44% of such targeting on the continent has occurred in each of these countries (22% of all cases per country). For example, on 28 June 2015, in Bujumbura Mairie in Burundi, two women who had voted were severely beaten by youths.18This event comes from one of ACLED’s local partners. For more on ACLED’s sourcing in Burundi, see this primer. 19Barangays refer to the smallest administrative division in the Philippines.

While government officials account for 16% of the targets of PVTWIP around the world (in navy in graph), the rate is significantly higher in Central Asia and the Caucasus (32%), the United States (25%), Latin America (24%), and Southeast Asia (23%). In Central Asia and the Caucasus, all reports of such violence have occurred in Afghanistan, where the rise of targeted violence against women officials has been specifically condemned (UN Women, 16 September 2013). In Latin America, two-thirds of PVTWIP against officials has occurred in Mexico, while in Southeast Asia, over half (56%) has taken place in the Philippines. Off-duty policewomen have faced targeting in both Afghanistan (The Interpreter, 23 August 2021) and Mexico (AP, 30 May 2021), while court employees, especially judges, face increased risk in Afghanistan (New York Times, 20 October 2021; Al Jazeera, 18 October 2021; BBC, 28 September 2021) and in the United States (CBS News, 30 May 2021; NPR, 20 November 2021). In the Philippines, various barangay officials have been targeted for violence, as have their family members.

Lastly, activists, HRDs, and social leaders face the largest proportion of PVTWIP around the world (in brown in graph), and this rate is even higher in East Asia (96%), the United States (75%), and the Middle East (50%). In East Asia, all such cases have been reported in China, where they largely target petitioners and human right activists. For example, on 24 February 2019, a human rights activist from Kunshan City in Jiangsu province was taken away and beaten in Beijing by personnel from the Kunshan Municipal Government. Her mobile phones and identity card were also forcibly taken away before she was sent to a temporary residence in Kunshan City where she was detained under surveillance (Civil Rights & Livelihood Watch, 26 March 2019). In the United States, Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists, as well as Black activists focused on other causes, are the primary targets of this violence. For example, on 9 December 2020, a Black woman activist organizing against sex trafficking and “corrupt leadership” in Hollywood, Florida was shot at by two unknown men outside her home. She believes she was specifically targeted (NBC Miami, 11 December 2020). In the Middle East, nearly half (47%) of this PVTWIP in the region has occurred in Iraq. For example, on 19 August 2020, unidentified gunmen assassinated a prominent activist and other women traveling with her in the center of Basrah when they opened fire at their car (International Federation for Human Rights, 28 August 2020; BBC News, 20 August 2020; Kurdistan 24, 22 August 2020; Rudaw, 23 August 2020).

Other Targets of PVTW20In addition to these identities, and those around women in politics noted above, when information about other salient associations is known, it is included in ACLED coding as an Associated Actor to civilians; this includes associations such as religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, refugee status, other occupations not directly linked to political processes (e.g. teachers, students, laborer, lawyers, aid workers, journalists), etc. For more information on Associated Actors, see the ACLED Codebook.

In addition to women in politics, other groups of women are also at high risk of political violence. Some, for example, are at greater risk as a result of their associations — such as women and girls who are relatives of targeted groups or persons, or who may be targeted as a means of reprisal against their family members. This includes cases in which a woman is subject to violence as a result of who she is married to, the daughter of, related to, or is otherwise personally connected to (e.g. candidates, politicians, social leaders, armed actors, voters, party supporters, etc.). For example, on 20 November 2019, in Villa Nueva, Guatemala, the daughter of a former mayoral candidate was found dead with bullet wounds, along with a companion (El Periodico, 20 November 2019). This category makes up a relatively large proportion of PVTW across many parts of Asia, though it is also seen in other parts of the world, like Latin America. Relatives can be targeted in order to put pressure on political exiles and others deemed to challenge the political status quo, for example (Foreign Policy Centre, 2017; Michaelsen, 2018). Overall, women targeted for their associations account for 5% of all PVTW globally.

Another subset of women facing greater risk include women accused of witchcraft or sorcery, or other mystical or spiritual practices that are typically considered taboo or dangerous within some societies. Belief in witchcraft is widespread in certain contexts, where it is usually used to explain ‘misfortune’ at the community or family level.21 In practice, “accusations of witchcraft result in gender-based violence that justifies social exclusion and even murder. …Women make up the majority of people who are targeted by accusations of witchcraft … ‘Rarely are men accused of witchcraft, or of being soul eaters or consequently excluded from their communities after suffering from violent attacks. Men suspected of such are more often feared and mistrusted by the population [rather than targeted with violence]’” (AWID, 2015). As a result of this accused identity impacting women in particular, it is included here.“Limited access to media, the opaque role of regional actors, and a dispersed population with low literacy rates” can all contribute to the targeting of individuals under this mantle (Clingendael, 2017). For example, on 5 June 2020, a group of young people stoned a woman to death over accusations of sorcery in Burungu, Masisi, in Nord-Kivu, DRC (La Prunelle RDC, 6 June 2020). This category makes up 2% of all women targets around the world, and is especially common in Africa.

Additionally, girls (i.e. children) face particularly high risks of violence. These cases include violence against a girl under the age of 18, specifically referred to by her age or explicitly referred to as a child/girl in reporting. For example, around 1 February 2021, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, a young girl was kidnapped, with kidnappers demanding a 40,000 USD ransom from her family, despite the fact that they make less than 1 USD a day (Haiti Standard, 17 February 2021). Violence targeting girls makes up 14% of all PVTW, underlining how girls face heightened risk both in war zones (Save the Children, 2021; UNICEF, 2021) as well as outside of areas affected by conventional conflicts (The Atlantic, 4 March 2018; UNICEF, 15 April 2021). Girls face particularly high risk in both the Middle East, especially in Yemen and Syria, and in Africa, especially in Sudan and the DRC, where they make up approximately 19% of the targets of PVTW in each region, though such targeting is reported in many countries around the world.

Types of PVTW

ACLED tracks multiple types of PVTW, corresponding to ACLED’s event types and sub-event types, outlined in the table.22 Sexual violence, (non-sexual) attacks, abductions/forced disappearances, and mob violence correspond to sub-event types in the ACLED dataset. Explosions/remote violence refers to all sub-event types which fall within that ACLED event type. For more on ACLED’s violence event types and sub-event types, see the ACLED Codebook. These include sexual violence, non-sexual attacks, abductions and forced disappearances, mob violence, and explosions and other forms of remote violence.

| Type of Violence | Definition | Example | % of PVTW |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Violence | Any action inflicting physical harm of a sexual nature, regardless of the age of the victim (i.e. including, but not limited to, rape). This includes conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), as well as sexual violence which occurs outside of the context of a conflict yet still in the public/political sphere. | Unknown armed men sexually assaulted an 8-year-old girl in the Lakes state of South Sudan, leaving her in critical condition. | 20% |

| Non-Sexual Attacks | Violence of a non-sexual nature by an armed actor targeting an unarmed individual; this is the most common form of PVTW around the world. | The Islamic State shot and killed an Iraqi IDP woman in the first section of Al Hol Camp in the Al Hasakeh countryside of Syria. | 60% |

| Abductions & Forced Disappearances | Kidnappings without reports of other physical violence; state-sanctioned arrests are not included here unless they are reported to have been conducted extrajudicially. | rmed men kidnapped a pregnant doctor, who is the daughter-in-law of Prime Minister Ariel Henry, inside her clinic in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, releasing her days later after a ransom was paid. | 12% |

| Mob Violence | When a spontaneously organized, unarmed (or crudely armed) mob, which may include ‘vigilantes’ or be linked to political parties or religious groups, engages in violence. | Three people kicked and repeatedly punched a transgender woman at a laundromat in the Kingman Park neighborhood of Washington, DC in the United States, with one individual stabbing her in the head and the arm, while the assailants called her anti-LGBT slurs. The incident is being investigated as a hate crime. | 7% |

| Explosions & Other Forms of Remote Violence | One-sided violence in which the tool for engaging in conflict creates asymmetry by taking away the ability of the target to respond; the tools used in such instances are explosive devices, including suicide bombs, remote explosives, grenades, etc. Given the less gender-targeted nature of this violence, it is less commonly used in PVTW around the world. | Unidentified armed militants blew up a girls school in the Nawda area of Farah city in Afghanistan. | 1% |

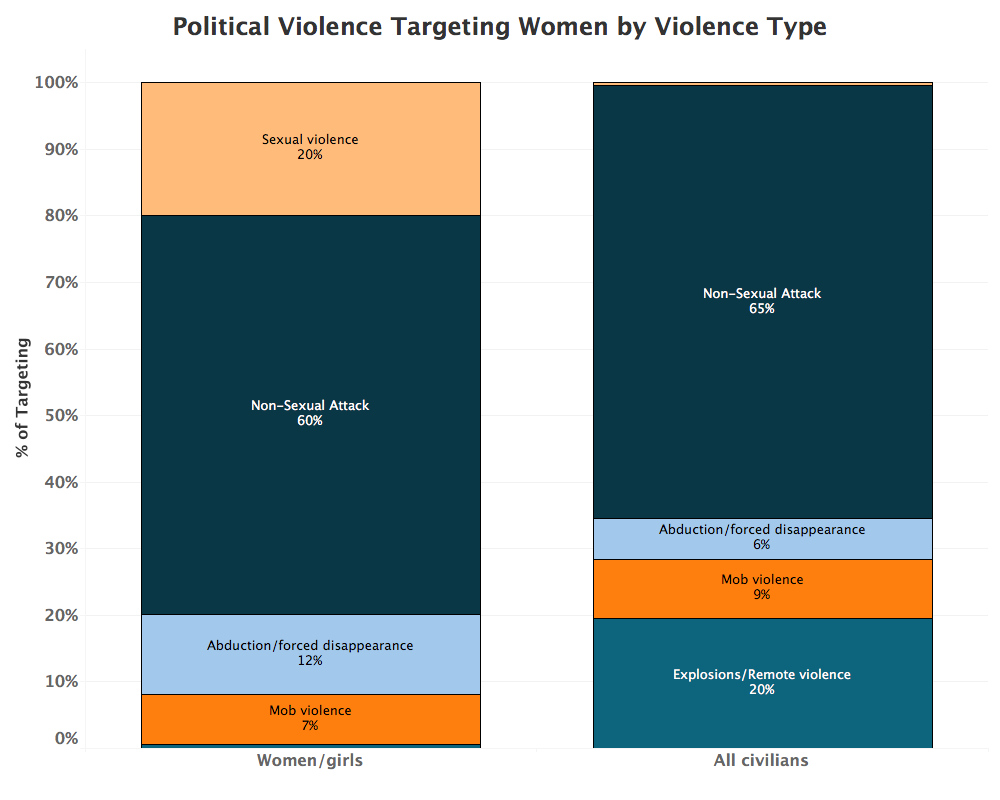

Sexual violence is often considered in women, peace, and security debates as the primary form of gender-based violence. While it does not make up the largest proportion of PVTW, accounting for 20%, it is the type of violence most disproportionately used to target women and girls relative to the civilian population at large (in peach in graphs). Civilians at large refers to men/boys as well as women/girls; this is not a gender disaggregation of civilian targeting. Abduction and forced disappearance (12% of PVTW) is also disproportionately used to target women (in blue in graph). Meanwhile, non-sexual attacks account for the majority (60%) of PVTW (in navy in graphs). Mob violence (7%) and explosions and other forms of remote violence (1%) are less common forms of PVTW (in orange and teal, respectively, in graphs).23These trends largely mirror those ACLED reported previously in the 2019 report, with non-sexual attacks being the primary form of targeting that women face around the world. One new development is that with ACLED’s expansion to new geographic regions and the more limited role of mob violence in these regions, abductions and forced disappearances now make up a larger proportion of PVTW than mob violence does.

Understanding the types of violence that disproportionately target women and girls relative to the broader civilian population can support efforts to address security equality — the concept that different groups ought to be equally protected from the threats that specifically affect their security (Olsson, 2018; (Kishi & Olsson, 2019). Only by identifying such distinctions can tailored policies and programming be developed to prevent or mitigate such specific threats, which may not be resolved with policies or programming aimed at reducing the threats to the population at large.

Types of PVTW by Region

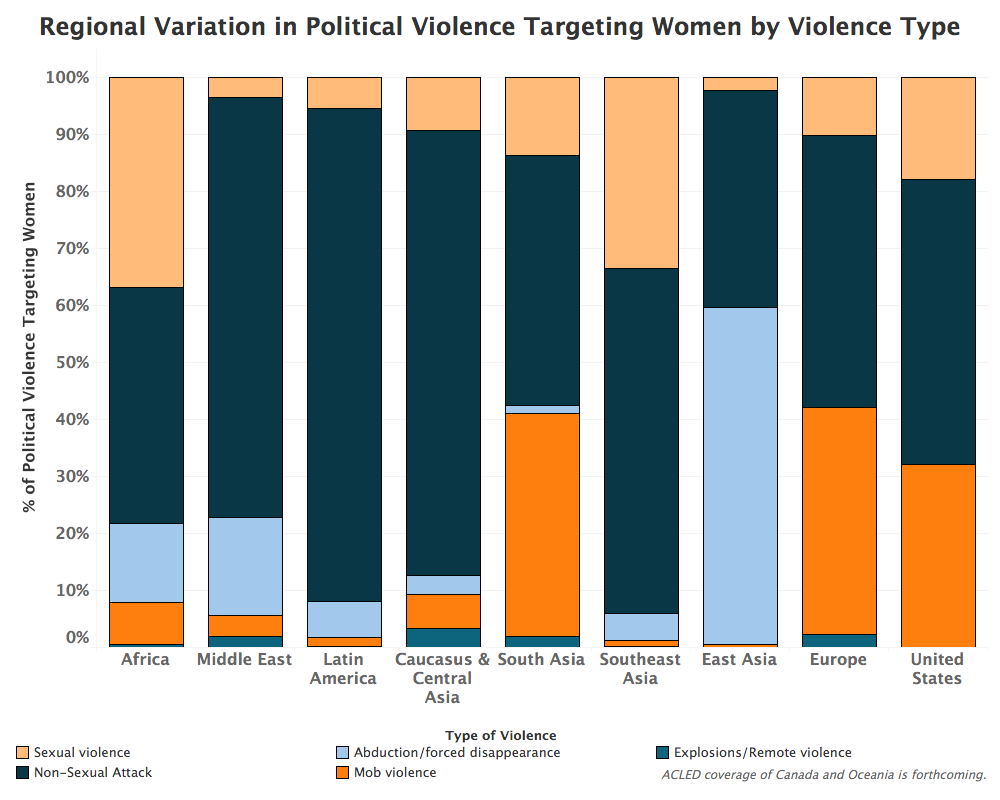

On average, the aggregate trends in tactics used to target women hold globally, with non-sexual attacks making up the majority of PVTW in most regions. However, the frequency of some forms of PVTW does vary by region (see graph).

Sexual violence (in peach in graph) is much more pervasive in Africa, where it comprises nearly 37% of all PVTW, especially in Sudan and the DRC. Sexual violence is also disproportionately more common (over 33% of PVTW) in Southeast Asia, especially in Myanmar. Both of these rates are considerably higher than the global rate of sexual violence, which is 20% of all PVTW.

Non-sexual attacks (in navy in graph) are more common in Latin America, Central Asia and the Caucasus, and the Middle East, where they account for 87%, 78%, and 74% of all PVTW events in each region, respectively. This is higher than the global rate of 60%.

Meanwhile, abductions and forced disappearances (in light blue in graph) are more common in East Asia, specifically in China where they make up the majority of PVTW in the country. This form of PVTW is also disproportionately common in the Middle East, especially in Syria. Abductions and forced disappearances make up 59% and 17% of all PVTW in East Asia and the Middle East, respectively — both higher than the global rate of 12%.

Mob violence (in orange in graph), on the other hand, is pervasive in both South Asia and Europe, making up over 39% of all PVTW in each of these regions — considerably higher than the global rate of 7%. While in South Asia this trend is driven particularly by dynamics in India, multiple countries contribute to this trend in Europe.

As reflected in aggregate trends, explosions and other forms of remote violence (in teal in graph) are the least common type of PVTW across all regions. They feature most prominently, however, in Central Asia and the Caucasus, driven especially by trends in Afghanistan. In this region, such violence makes up over 3% of all PVTW — higher than the global rate of 1% of all PVTW.

Types of PVTWIP by Region

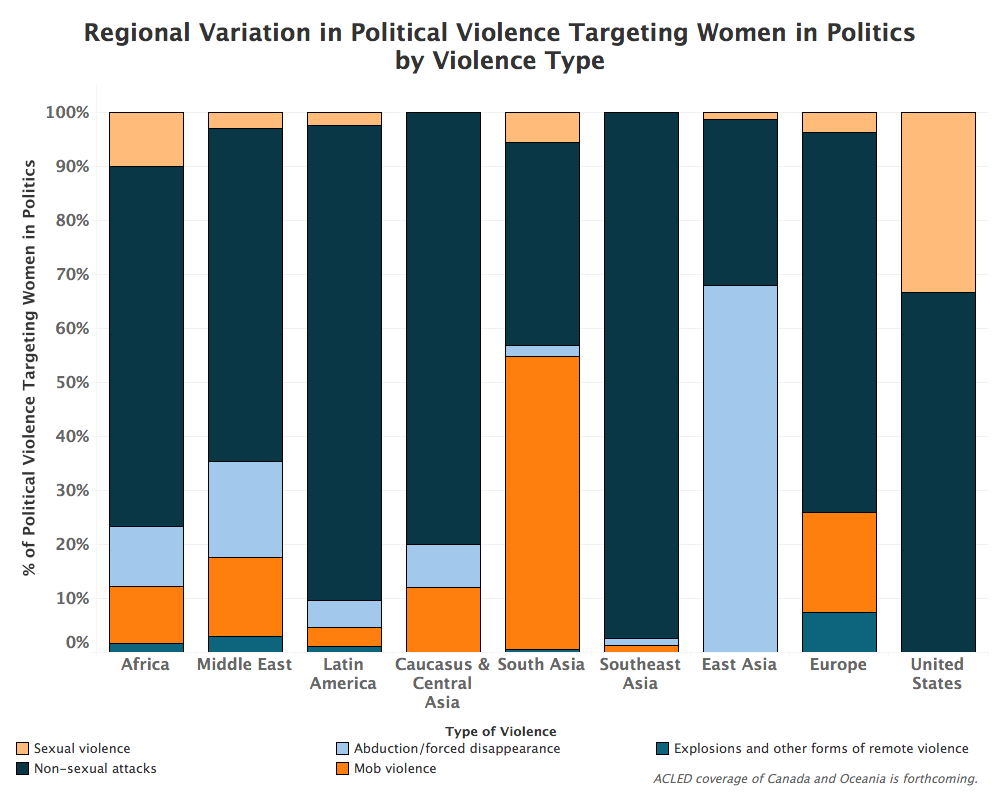

The trends in types of PVTWIP are quite similar to the trends in PVTW more broadly, though with several exceptions (see graph). Non-sexual attacks are the primary way in which women in politics are targeted (66% of the time). Mob violence, and abductions and forced disappearances, each make up 14% of PVTWIP, respectively. Five percent of PVTWIP is sexual violence. And the smallest proportion of PVTWIP (1%) consists of explosions and other forms of remote violence.

Abductions and forced disappearances (in blue in graph) are used disproportionately in East Asia and the Middle East to target women in politics, making up 68% and 18% of all PVTWIP in each region, respectively — higher than the rate of 12% seen for events targeting women more largely. For example, in East Asia, on 20 March 2019, a woman human rights defender was arrested from her home in Shanghai, China by police together with her husband; while her husband was released on probation the following month, she was held incommunicado for more than six months until authorities announced that she was charged with “subversion of state power” in October 2019 (China Human Rights Defenders, 21 October 2019). In the Middle East, on 19 August 2020, a member of the Socialist Party of the Oppressed (ESP) was extrajudicially abducted by plainclothes police officers in Ankara, Turkey; the target was approached by people who identified themselves as police officers who forcefully put her in a van, questioned her about her political involvements and activities, and pressured her to act as an informant (Mezopotamya Ajansı, 21 August 2020). She was released the same day after being threatened with terrorism charges if she did not leave town in a week.

Mob violence (in orange in graph) is disproportionately common in South Asia and Europe, where it makes up 54% and 19% of all PVTWIP in each region, respectively — considerably higher than the rate of 7% seen for PVTW more largely. For example, in South Asia, in mid-December 2018, a Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) candidate and her supporters were injured in an attack by a violent mob while campaigning in Mansiri Palpara area, in Netrakona, Bangladesh (The Daily Star, 16 December 2018). Meanwhile, in Europe, on 15 June 2019, a group of people attacked a New Democracy member of parliament and her team who were campaigning and distributing leaflets in Perama, Piraeus in Greece; a young woman campaigner was injured in the attack (Tovima, 15 June 2019).

Non-sexual attacks too (in navy in graph) are used to target women more largely 60% of the time. Non-sexual attacks (in navy in grap) are the most common form of PVTW and PVTWIP, at 60% and 66%, respectively. However, non-sexual attacks are an especially common form of PVTWIP in Southeast Asia (97% of the time), Latin America (88% of the time), and in Central Asia and the Caucasus (80% of the time), where they make up an even larger majority of events. In Southeast Asia, for example, on 1 July 2016, in Mariveles, Bataan, in the Philippines, unidentified motorcycle-riding men shot dead a woman environmental activist in Barangay Lucanin (EuroNews, 12 March 2021). She was a United Citizenry of Lucanin and Kilusang Pambansang Demokratiko (KPD) president, as well as a Coal Free Bataan Movement member; the organization was opposed to a coal storage plant project in their neighborhood (Front Line Defenders, 2021). In Latin America, on 12 November 2018, in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, unidentified armed men broke into the house of a community leader and shot her dead (La Prensa, 13 November 2018). In Central Asia and the Caucasus, on 21 January 2021, a Xinjiang-born female ethnic Kazakh refugee and activist, who had been involved in a public campaign of exposing China’s internment camps for Turkic minorities, was attacked by unknown individuals near her residence in Almaty city in Kazakhstan (Azattyq, 22 January 2021). This somewhat mirrors trends in PVTW more largely, where non-sexual attacks are disproportionately common in Latin America, Central Asia and the Caucasus, and the Middle East.

While the PVTWIP trends above all generally match the broader trends in PVTW in these regions, some discrepancies are explored below.

Sexual violence (in peach in graph) is used 33% of the time to target women in politics in the United States — higher than the rate of 20% for PVTW globally. For example, on 19 July 2020, two transgender women and BLM activists were forced to strip by four officers at the Turner Guilford Knight Correctional Center in Miami, Florida after the officers learned that the women were transgender (NBC Miami, 8 September 2020; Miami New Times, 18 May 2021). This differs from broader trends in the prevalence of sexual violence targeting women, where sexual violence is disproportionately common in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Explosions and other forms of remote violence (in teal in graph) are also used less frequently to target women in politics, though they are disproportionately common in Europe (over 7% of the time) and in the Middle East (3% of the time) — higher rates than PVTW globally (1% of the time). In Europe, for example, on 24 July 2020, a “fire bomb” was thrown at the home of an Iranian-Swedish politician in Karlskoga, Sweden (Omni, 26 July 2020; Dagens Nyheter, 26 July 2020). The Christian Democrat member of parliament and women’s activist had received threats a few days before after criticizing the Iranian regime and speaking against honor violence (SVT, 26 July 2020). She believes the Iranian regime is behind the attack; her house had been previously targeted, with unknown individuals throwing stones at the windows and slashing car tires (Expressen, 26 July 2020). In the Middle East, on 16 February 2020, an IED exploded at the home of a woman member of parliament in Akaika in Suq al Shuyoukh district in Iraq, though it resulted in no reports of damage or casualties (Awla News, 16 February 2020). This too differs from trends in the prevalence of this type of violence in targeting women more largely, where explosions and other forms of remote violence are disproportionately used in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

Perpetrators of PVTW

ACLED tracks multiple types of actors responsible for PVTW, corresponding to ACLED’s agent types and actor groupings,24State forces, rebels, political militias (including gangs), communal militias, violent mobs (rioters), and other/external forces correspond to agent types in the ACLED dataset (i.e. interaction types). Unidentified armed groups refer to all so-named actors in the ACLED dataset. For more on ACLED’s agent/actor types, see the ACLED Codebook. outlined in the table.25Rounding results in these numbers appearing to not add up to 100%. These include named actors — such as state forces, rebels, political militias and gangs,26ACLED has a relatively restrictive understanding of political violence and, by definition, it does not include crime. But ACLED includes gang violence when it is used towards meeting overt political goals. Further, when gang activity directly and fundamentally challenges public safety and security, it is deemed ‘political violence’. In countries where it meets this threshold, criminal violence involving gangs is coded by ACLED as akin to ‘political violence’. For more on these methodological considerations and a list of countries where this threshold is met, see this methodology primer. communal militias, and other/external forces — as well as unnamed actors — such as anonymous or unidentified armed groups (UAGs),27UAGs are considered to be engaging in political violence based on context. When an armed, organized group attacks civilians, especially when without criminal acts (such as stealing), then it is considered the sign of a politically motivated decision. Criminal gangs, meanwhile, may attack civilians but for the purposes of criminality. and violent mobs.28Violent mobs believe their role to be the delivery of justice, often emerging to address internal security arrangements within a community, and take enforcement of what they believe to be the law into their own hands. In this way, they challenge the state’s monopoly on the use of legitimate force, and are hence viewed as agents of political violence (Kishi, 2017). Violent mobs are spontaneous by definition. If a violent act was spontaneous (e.g. formed in response to something, crudely armed or not armed at all, etc.) then it is coded as involving a violent mob. If a violent act was organized or planned (e.g. perpetrators are armed, arrive and leave together, share uniforms, etc.), then it is coded as involving a named group, or as an unidentified armed group if the name is not known.

| Type of Perpetrator | Definition | Example | % of PVTW |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Forces | The formal state security apparatus, which includes military and police units and divisions therein. | A woman who was a human rights defender was intercepted at the National Public Complaints and Proposals Administration in Xicheng district in Beijing, China, and has since remained uncontactable. | 20% |

| Rebels | Political organizations whose goal is to counter an established national governing regime by violent acts, who have a stated political agenda for national power (either through regime replacement or separatism), are acknowledged beyond the ranks of immediate members, and use violence as their primary means to pursue political goals. This category includes: groups considered to be ‘extremist’ or ‘terrorist’ if they seek to overthrow the government in order to establish an Islamist state or caliphate; foreign armed groups who seek to overthrow the government in another country; separatist groups. | Presumed Katiba Macina militants (part of JNIM) assaulted women for not wearing veils while working at a market garden in the village of Konga in Burkina Faso. | 8% |

| Political Militias / Gangs | Armed, organized political gangs; these groups act on behalf of political elites, including elites who are in power, and are often created for a specific purpose or during a specific time period, and for the furtherance of a political purpose by violence. Such groups do not challenge the state as they do not seek to overthrow regimes. ‘Criminal’ gangs are included here under certain contexts. | Suspected MS-13 gang members abducted a woman in San Cayetano Colonia, El Salvador while she was on her way home; she was believed to be an informant of a rival gang. | 24% |

| Communal Militias | Armed and violent groups that have organized around a collective, common feature including community, ethnicity, region, religion or, in exceptional cases, livelihood; such groups often engage in ‘communal violence’, in which they act locally, in the pursuance of local goals, resources, power, security, and retribution. An armed group claiming to operate on behalf of a larger identity community may be associated with that community, but not represent it; recruitment and participation in the group are by association with the identity of the group. | Dan Na Ambassagou militiamen killed two women in the Dogon village of Okoyeri-Dogon in Mopti, Mali. | 5% |

| Other & External Forces | All other named and organized perpetrators of PVTW, which can include foreign militaries, coalitions, international organizations, private security forces, mercenaries, etc. | Israeli military forces physically assaulted a Palestinian woman by pepper spraying her in the face after Friday prayers in the Al Aqsa Mosque in Palestine; she suffocated from inhaling pepper spray. | 1% |

| Anonymous or Unidentified Armed Groups (UAGs) | Cases in which more information is not known about the perpetrator of a PVTW incident; this is the most common category of perpetrator globally. Such groups only engage in organized violence (not ‘mob violence’). | An unidentified armed group threw a grenade at the headquarters of an aid agency in Ad Dali city in Yemen, injuring two women staff members; sources speculate that the INGO might have been targeted by people who accused it of inciting divorces in the governorate as it provided financial support to divorced women. | 33% |

| Violent Mobs | Spontaneously organized, unarmed (or crudely armed) mobs, often with links to political parties or religious groups; such groups tend to be more clandestine given they do not always have formal links to named entities, seeking justice against perceived criminals or ‘witches’. Such groups only engage in ‘mob violence’. | A group of assailants hurled at least five crude bombs at the residence of the sister of the Minister of Road Transport and Bridges, who was also an MP in Noakhali, Bangladesh. | 7% |

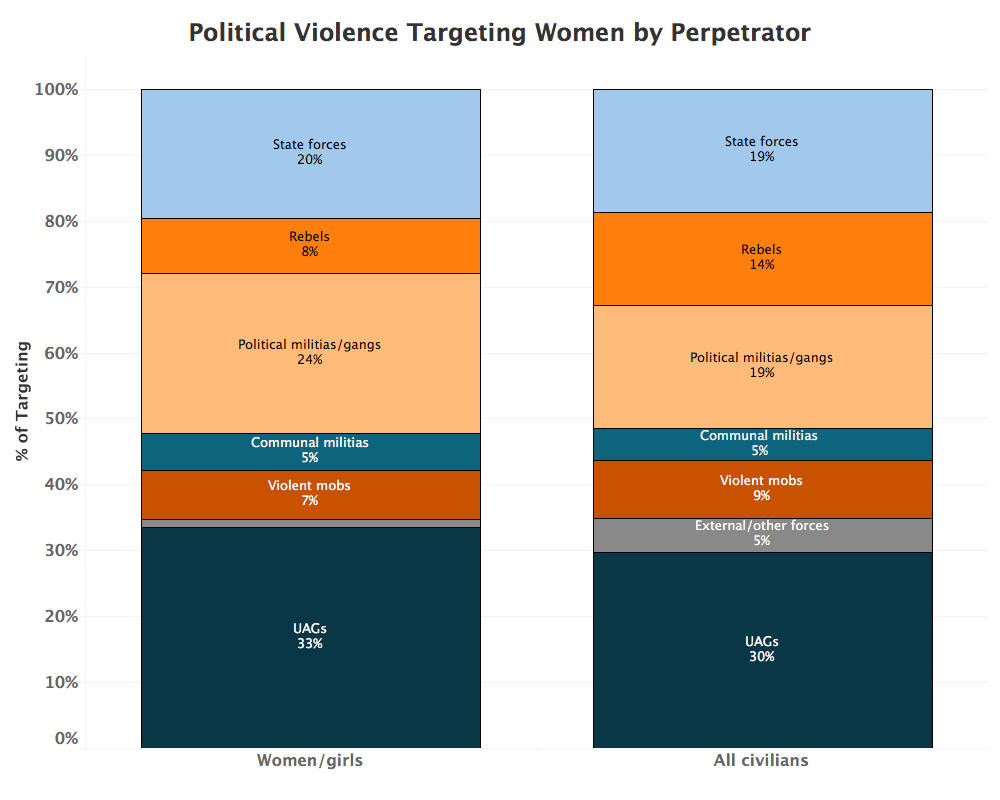

One-third of PVTW is perpetrated by UAGs (see navy in graph). Past ACLED and PRIO research outlines multiple important issues about this trend: “That we know so little about who the perpetrators are in many acts of PVTW can be the result of insufficiently detailed reporting, due to a lack of capacity to conduct gender-aware reporting or due to the complexity of crisis contexts. However, a more important reason is the wish of the perpetrator to preserve strategic anonymity. Some actors may ‘outsource’ PVTW to agents to avoid responsibility. That such groups are doing the bidding of others is probable, given patterns in the types and geography of violence in many crisis contexts. [The prevalence of PVTW perpetrated by unidentified agents] underscores how important it is to include such actors in data collection efforts, or we risk minimizing the threat that women face” (Kishi and Olsson, 2019).

One-quarter of PVTW, meanwhile, is carried out by political militias and gangs (in peach in graph), while one-fifth is carried out by state forces (in blue in graph). Rebel groups are responsible for 8% of PVTW (in orange in graph), as are violent mobs (in brown in graph), while comunal militias perpetrate 5% of PVTW (in teal in graph). Lastly, external and other forces are responsible for 1% of PVTW (in gray in graph).29These trends largely mirror those ACLED reported previously in the 2019 report, with non-sexual attacks being the primary form of targeting that women face around the world. One new development is that with ACLED’s expansion to new geographic regions and the more limited role of mob violence in these regions, abductions and forced disappearances now make up a larger proportion of PVTW than mob violence does.

A number of perpetrators — including state forces, political militias/gangs, and UAGs — disproportionately target women relative to the civilian population at large (see graphs), suggesting that tailored policies and programming would need to be developed in order to address such specific threats, without which establishing security equality would not be possible (Olsson, 2018; (Kishi & Olsson, 2019).

Perpetrators of PVTW by Region

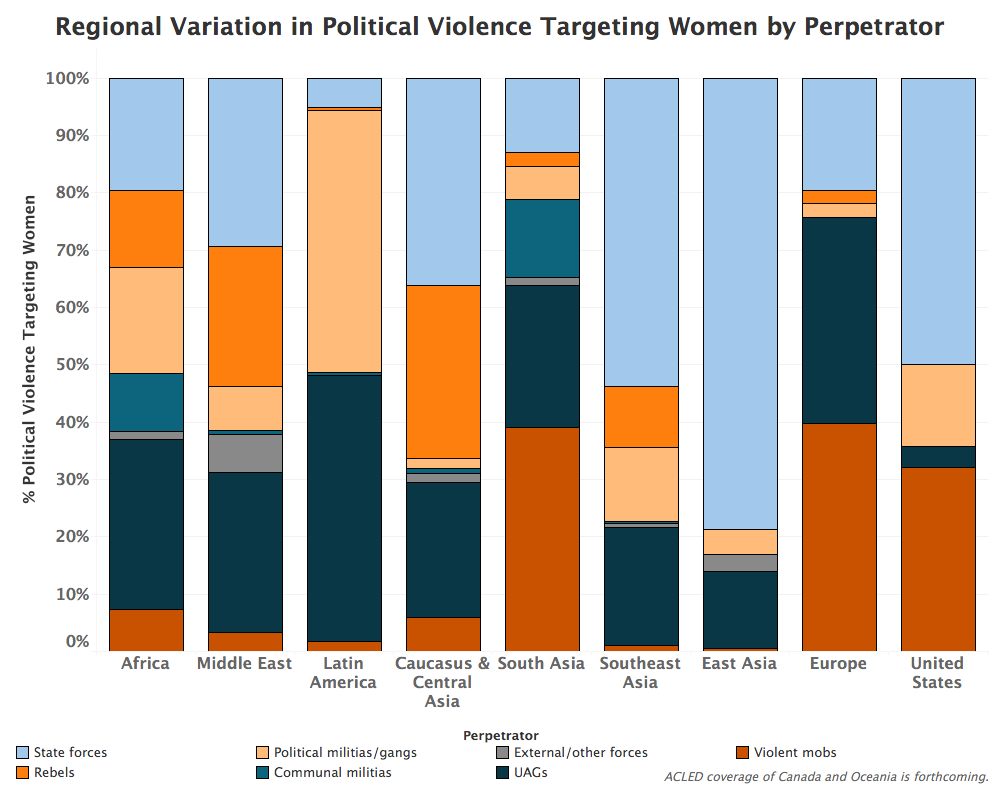

While UAGs are responsible for a considerable proportion of PVTW across all regions, the prevalence of different perpetrators in carrying out PVTW varies, with certain perpetrators more active in certain contexts (see graph).

Rebels (in orange in graph), meanwhile, are more active in Central Asia and the Caucasus, especially the Taliban in Afghanistan,30 Following the fall of Kabul in August 2021, the Taliban are no longer coded as a rebel group, and are now considered to be the de facto state power in Afghanistan. For more, see this Afghanistan methodology primer. and in the Middle East, especially the Islamic State (IS) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (QSD) in Syria. Rebels make up over 30% and over 24% of all PVTW in those regions, respectively, which is considerably higher than the 8% of PVTW such groups are responsible for in the aggregate.

Meanwhile, gangs (in peach in graph) are disproportionately active in Latin America, especially in Mexico and Brazil, responsible for nearly 46% of PVTW in the region — almost twice the global rate of 24%.

Communal militias (in teal in graph) are more active in South Asia, especially caste militias in India, and in Africa, where PVTW is frequently perpetrated by various ethnic militias. Such groups are responsible for over 13% and over 10% of PVTW in those regions, respectively — well above the global rate of 5%.

External and other forces (in gray in graph) are the least active across all regions. This may be because the threat such groups pose to civilians tends to take the form of collateral damage during explosions or remote violence events, rather than through purposeful or direct targeting. Nevertheless, such actors are responsible for a disproportionate amount of PVTW in the Middle East, where they account for nearly 7% of all PVTW in the region — over twice as high as the global rate of 3%. This trend is driven especially by the Turkish gendarmerie in Syria and the Israeli military in Palestine.

Violent mobs (in brown in graph) are responsible for over 39% of PVTW in both South Asia, especially in India, and Europe — a rate over five times as high as that seen around the world, where mobs are responsible for 7% of all PVTW. Meanwhile, although UAGs (in navy in graph) are responsible for a third of PVTW around the world, the rate is even higher in Latin America (46%) and in Europe (36%).

Perpetrators of PVTWIP by Region

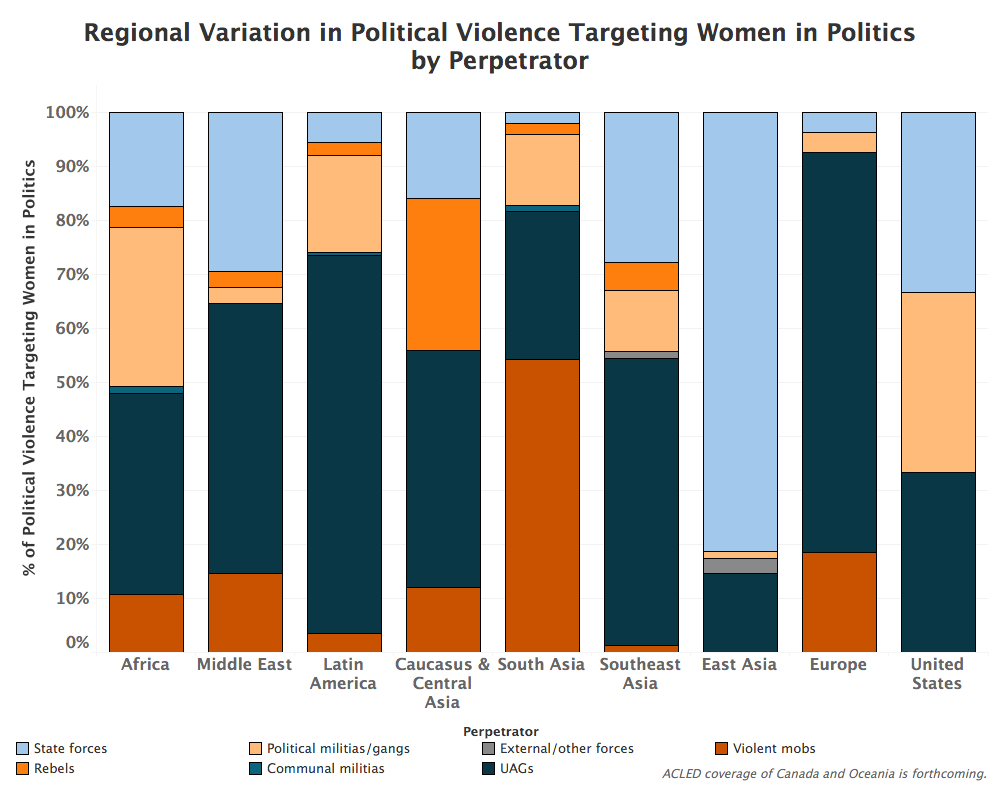

The trends around the types of PVTWIP are quite similar to the broader trends in PVTW discussed above, though again with a few exceptions (see graph). UAGs are the primary perpetrator of PVTWIP (45% of the time). State forces are responsible for 20% of such targeting. Political militias and gangs carry out 17% of PVTWIP, while violent mobs are responsible for 14%. Rebel groups perpetrate 3% of PVTWIP, while communal militias, and external or other forces, are each responsible for less than 1% of PVTWIP.

Violent mobs (in brown in graph) are responsible for 7% of PVTW more largely around the world, though are responsible for 54% of PVTWIP in South Asia and 19% of PVTWIP in Europe. In South Asia, for example, on 19 July 2021, a mob made up of eight people from the Muslim community pelted stones at and attacked a BJP sarpanch and her daughter with sharp-edged weapons at Sunderbani city in Jammu and Kashmir, India over an alleged land encroachment issue (Early Times, 19 July 2021). In Europe, on 1 February 2021, a woman activist of the Unite Against Fascism and Racism (UCFR) was beaten by around 10 men who were Vox party supporters during a Vox rally election campaign in Barcelona, Spain (La Provincia, 22 April 2021). The woman said that one of the party members recognized her from her activist work, resulting in him and his group starting to beat and insult her, calling her “puta” (translation: a whore) (Publico, 22 August 2021).

State forces (in blue in graph) are disproportionately active in targeting women in politics in East Asia and the United States, making up the perpetrators of 81% and 33% of all PVTWIP in each region, respectively — higher than the rate of 20% seen in the targeting of women more largely. The examples shared above of the woman human rights defender arrested from her home in Shanghai, China by police and the two transgender women BLM activists who were forced to strip by four officers at a correctional center in Miami, Florida, reflect this trend. This somewhat mirrors trends in PVTW more largely, where such violence makes up a disproportionately higher rate of PVTW in East Asia and Southeast Asia.

Rebels (in orange in graph) are disproportionately active in targeting women in politics in Central Asia and the Caucasus (28%), making up the perpetrators of 28% of all PVTWIP in the region — higher than the rate of 8% seen in the targeting of women more largely. For example, on 29 December 2018, a woman activist was kidnapped and killed by Taliban militants who accused her of adultery in Dashti Qala district, Takhar in Afghanistan (New York Times, 4 January 2019). Again, this somewhat mirrors broader trends in PVTW where rebels account for a disproportionately higher rate of PVTW in Central Asia and the Caucasus and the Middle East.

UAGs (in navy in graph) are responsible for one-third of all PVTW around the world. They are disproportionately responsible for PVTWIP, however, across nearly all regions — underlining how so much of this violence is carried out by anonymous agents who are able to enjoy impunity for their actions. UAGs are responsible for particularly high rates of PVTWIP in Europe and Latin America, at 74% and 70%, respectively — mirroring regional trends in overall PVTW as well. For example, in mid-August 2019, unknown individuals sabotaged the brakes of the car belonging to the mayor of Ghelauza of the Straseni district in Moldova, causing her to have an accident in which she broke a leg (Moldova.org, 17 August 2019). In Latin America, on 27 October 2018, in Pacajus, Ceara, Brazil, a woman was shot and killed while she was participating in a political rally for the Workers’ Party candidate. A white car approached her during the rally when occupants shot her and then fled the scene (Globo, 5 November 2018).

The trends above generally mirror broader PVTW trends in these regions, at least to a degree (see above). Some discrepancies are explored below.

Political militias and gangs, as well as ‘sole perpetrators’31The coding of ‘sole perpetrators’ is unique to the US context within ACLED, capturing cases where violence is carried out by a single “lonewolf” without an affiliation to a specific named group. The actor is used when an individual is not clearly part of a group and acts alone, such as in the case of mass attacks (e.g. mass shootings, “lone wolf” bombings, car ramming attacks on crowds, etc.) or politically-motivated attacks. For more on ACLED’s coding methodology of the US context, see this primer. (in peach in graph), are disproportionately active in targeting women in politics in the United States (33%) and in Africa (29%) — higher than the rate of 24% seen in the targeting of women more largely. For example, in the United States, on 19 July 2020, a man, posing as a FedEx delivery man, shot the family members of a woman US District Judge close to New Brunswick, New Jersey, killing her son, and seriously injuring her husband; the judge remained unharmed, as reports indicate that she was in the basement of her home at the time of the attack (USA Today, 20 July 2020). She had been nominated by former President Barack Obama and was the first Latina magistrate in New Jersey. The suspect was a self-described anti-feminist and was later found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound (USA Today, 3 August 2020). In Africa, on 28 March 2020, members of the Imbonerakure, the youth wing of the ruling National Council for the Defence of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) party, raped and beat up a woman member of the National Congress for Liberation (CNL) party, also assaulting her husband, in Kirambi, Burundi (Radio RPA, 30 March 2020). This differs from trends in the prevalence of political militias and gangs targeting women more largely, where they disproportionately target women in Latin America (see above).

Meanwhile, external and other forces (in gray in graph), including private security forces, are disproportionately active in targeting women in politics in East Asia, where they are responsible for nearly 3% of all PVTWIP — this is higher than their rate of involvement in PVTW more largely (1%). For example, on 13 May 2018, two women members and activists of the LGBT community were beaten by private security guards at the 798 Art Zone in Chaoyang District in Beijing, China while distributing rainbow badges and flyers to raise awareness about the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia (RFA, 15 May 2018). This differs from trends in the prevalence of this type of perpetrator in targeting women more largely, where they disproportionately target women in the Middle East (see above).

Communal militias are responsible for 5% of all PVTW around the world. Such groups, however, are involved in the targeting of women in politics far less; they are responsible for less than 2% of PVTWIP, or for none at all, across all regions. Such actors are often more active in the ‘periphery,’ and far more removed from engagement in the national political arena (Raleigh, 2014).

Regional Trends in PVTWIP over Time32The trends explored here represent various time periods across different regions, reflecting ACLED’s varied temporal coverage of countries. This coverage can be found in this table. When considering trends over time across countries, taking into account such variation is crucial so as to not conflate lack of coverage with lack of violence. When comparing trends within countries between regions, however, the impact of different temporal coverage across countries is more limited. This is why trends are compared within regions (e.g. PVTW is trending upwards in Africa), but not across countries (e.g. PVTW has been higher in Africa than in Latin America).

In recent years, PVTWIP has been increasing across nearly all regions of ACLED coverage.33These trends pertain to European countries for which ACLED coverage extends back to 2018; European countries for which coverage begins in 2020 do not yet have multiple years of data to allow for such comparisons. See our current list of country and time period coverage here. In Africa, this has been driven largely by a trend of targeting women political party supporters in Burundi, especially at the hands of the Imbonerakure, since 2018. The Imbonerakure has been a potent source of insecurity in Burundi, particularly since rising to prominence in 2015 as a result of then President Pierre Nkurunziza’s controversial (and potentially unconstitutional) bid for a third term, which resulted in a violent political crisis (for more on the Imbonerakure, see this analysis piece). The Imbonerakure continues to act as a violent pro-government militia in the country, especially around contentious periods like elections (for more on election violence in Burundi, see this analysis piece). Women political party supporters have also long faced heightened risk in Zimbabwe, with spikes often seen around elections, most recently in 2017 in the lead-up to the 2018 general election, with the ZANU-PF, the ruling party since independence, responsible for the majority of the increasing violence (for more on election violence in Zimbabwe in the lead up to the 2018 election, see this analysis piece).

In Central Asia and the Caucasus, the rise in PVTWIP in recent years is driven largely by trends in Afghanistan, though more recently also in Kazakhstan. In Afghanistan, government officials, such as off-duty policewomen and court employees, have seen increased targeting specifically, with attacks perpetrated by UAGs and the Taliban (The Interpreter, 23 August 2021; New York Times, 20 October 2021; Al Jazeera, 18 October 2021; BBC, 28 September 2021). Meanwhile, in Kazakhstan, women activists have seen a rise in targeting by both organized yet anonymous/unknown armed groups and violent mobs. Violence has targeted both opposition activists as well as women advocating for specific rights, such as women’s rights, environmental rights, and LGBT rights (RFERL, 27 July 2021; IPHR, 29 October 2021; HRW, 10 March 2021; Amnesty International, 2 July 2019).

In Europe,34These trends pertain to European countries for which ACLED coverage extends back to 2018; European countries for which coverage begins in 2020 do not yet have multiple years of data to allow for such comparisons. See our current list of country and time period coverage here. PVTWIP has risen in Ukraine since 2020, with violence targeting activists (Amnesty International, 2020) — such as human rights, women’s rights, Roma, and anti-corruption activists — as well as government officials, specifically judges.

PVTWIP has also been increasing in recent years in the Middle East. The targeting of activists in Iraq has contributed significantly to this trend. Attacks on activists have become especially common since 2019, increasing dramatically again between 2019 and 2020. Such targeting is regularly carried out by UAGs, though many believe that Iranian-backed militias within the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) are to blame (New York Times, 2021; France24, 2020).

In Southeast Asia, PVTWIP has trended upwards in recent years, driven especially by targeting in the Philippines. There, women candidates for office, politicians, political party supporters, government officials, and activists have all faced frequent targeting. The violence has been largely carried out by anti-drug ‘vigilantes,’ which often have clear links to the state (ACLED, 18 November, 2021; ACLED, 18 October 2018); Human Rights Watch, 5 March 2017; Amnesty International, 31 January 2017; ICC, 14 June 2021), the Philippine military, and UAGs, which could have links to the state as well. In the past, the government has issued lists including the names of opposition politicians and supporters, alleging they have links to drug suspects or communists — labeling them in effect as persona non grata to be targeted. With President Rodrigo Duterte’s mandate coming to an end and elections scheduled for May 2022, such targeting may increase (for more on how the Duterte administration has used the drug war to target civilians, including opposition, see this report).

In South Asia, while PVTWIP has been generally trending upwards, there was a decline in 2020 relative to 2019. This is likely driven by two main factors: (1) much of the violence in South Asia takes place in India by virtue of its extremely large population, and (2) PVTWIP tends to spike around elections, such as during the 2019 general election in India. It is not surprising to see a decline in PVTWIP in the country post-election, contributing to the broader regional decrease (UN Women, 2021). Political party supporters are most at risk of PVTWIP in the region, especially in India though also in Bangladesh as well (for more on elections in India, see ACLED’s Indian Election Monitor; for more on violent political rivalries in Bangladesh, see this ACLED report).

In Latin America, PVTWIP spiked in 2020 compared to 2019, driven largely by increases in violence in Brazil and Mexico. In Brazil, municipal elections were held in November 2020, and women candidates for office faced heightened targeting in the lead up to the elections (for more, see this ACLED infographic). In Mexico, meanwhile, government officials, specifically women police, have faced increased targeting since 2020 as cartels have begun to increasingly attack off-duty officers (AP, 30 May 2021). In Colombia, rates of PVTWIP have also remained worryingly high in recent years. Non-sexual attacks, often carried out by unidentified armed groups, are prevalent in the departments of Norte de Santander and Cauca, and typically target activists, human rights defenders, and social leaders (for more on the targeting of vulnerable groups in Colombia, see ACLED’s mid-year update on 10 conflicts to worry about in 2021 as well as this joint report).

The only region where ACLED data show a steady decrease in PVTW and PVTWIP is East Asia. However, while the data suggest that violence is trending downward, the reality may be different. The decline has been driven specifically by trends in China, which has been home to nearly all PVTW in the region. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, political violence at large has declined in the country; fewer people have been petitioning in light of strict lockdowns, and also because of the special circumstances that the pandemic has presented. Nevertheless, authorities have held people in strict quarantines, with some alleging that police are keeping them quarantined without valid reason. In such cases, reports may note that a petitioner had tested negative for COVID-19 and was still kept in quarantine, though often no further detail is available. As testing negative is not necessarily the only criteria to meet in order to avoid undergoing quarantine, with regulations often changing, such cases are not currently coded as forced disappearances by ACLED. That said, there is reason to suspect that authorities may be exploiting the pandemic restrictions like quarantines to target petitioners, including women, with less scrutiny (New York Times, 30 July 2020); ACLED will adapt methodological decisions as new information comes to light (for more on how the COVID-19 pandemic has been used by states to justify forms of repression, see ACLED’s final COVID-19 Disorder Tracker report). Nevertheless, despite the downward trend, China still ranks as one of the most violent countries for women in politics since 2020.

Conclusion

While far from uniform, PVTW and PVTWIP are on the rise in most regions of the world. Women engage in politics in myriad ways — as candidates, voters, supporters, activists — and the risks they face are varied in turn. Women politicians often face different risks than women human rights defenders or women who serve as government officials. These threats can vary based on the location where women are based; the type of violence used against them; the perpetrators of such violence; and the time period — with some risks intensifying for women in politics during contentious periods like elections.

Understanding these different risks, and how they diverge from the risks faced by the wider population, is an important step toward identifying effective strategies to protect women from the particular threats that affect their security. Recognizing these unique threats is crucial if half of the world’s population is to engage freely and safely in politics. In the absence of data-driven and context-specific initiatives aimed at establishing real security equality, the gains being made by women’s increased participation in political processes could be lost.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.