10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Haiti

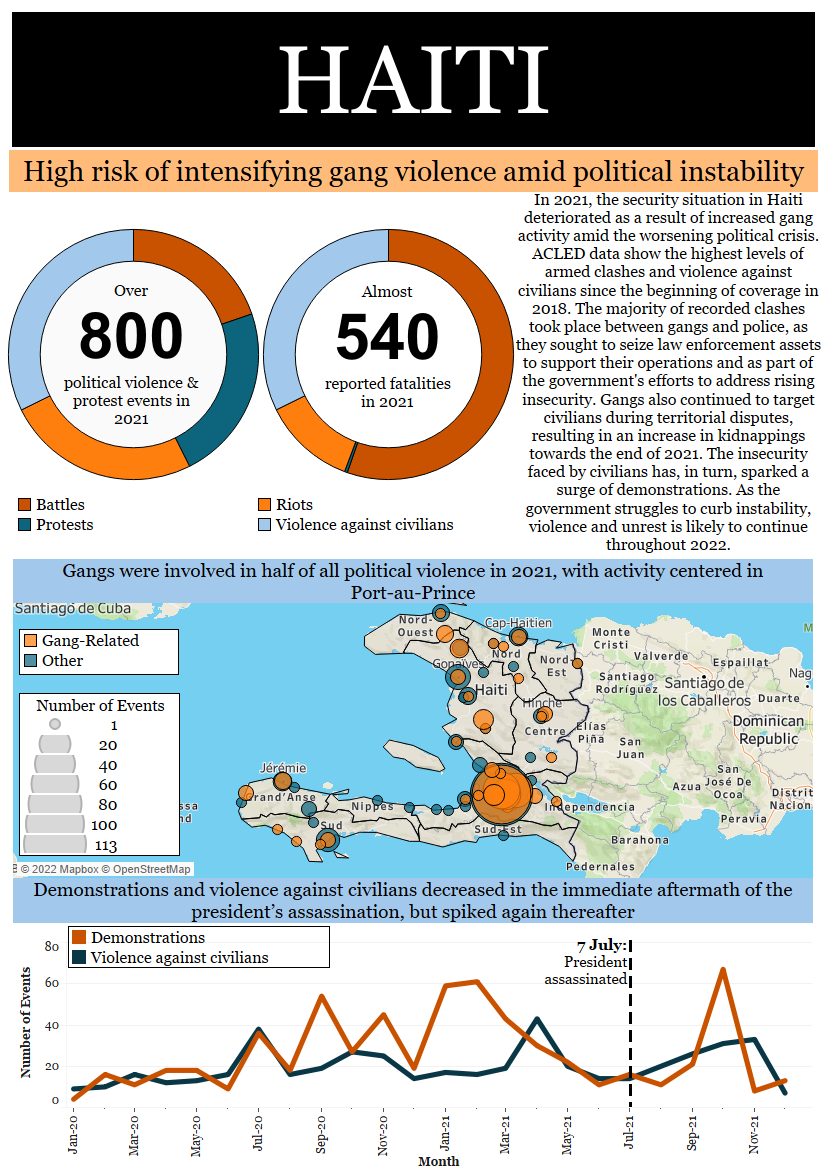

High risk of intensifying gang violence amid political instability

In 2021, the security situation in Haiti deteriorated as a result of increased gang activity amid the worsening political crisis. ACLED data show the highest levels of armed clashes and violence against civilians since the beginning of coverage in 2018. Insecurity and political instability, exacerbated by the killing of former President Jovenel Moise on 7 July, continued to fuel unrest throughout the year.

The first half of 2021 was marked by strong anti-government mobilization, prompted by disagreements over the constitutional end of then-President Moise’s term. Members of the opposition claimed that Moise’s term was due to end in February 2021, five years after former President Michel Martelly stepped down. Moise, however, remained in power, asserting that his term would not expire until February 2022, five years after his inauguration (BBC, 15 February 2021). Moreover, his scheduling of a referendum to transition Haiti from a semi-presidential to a full presidential system sparked widespread unrest. The constitutional reform also included provisions to allow presidents to serve two consecutive five-year terms amid concerns that President Moise was tightening his grip on power. Against this backdrop, nearly 60% of demonstration events last year took place during the first half of 2021 (for more, see the mid-year update to last year’s special report on 10 conflicts to worry about in 2021). A large portion of demonstrations were held to oppose the government and its reforms, with frequent demands for the president’s resignation.

In the same period, a significant number of demonstration events were also prompted by insecurity driven by increased gang warfare and continuing attacks on civilians. Gang operations are often linked with political movements and, at times, are allegedly conducted in collusion with the ruling elite (France 24, 27 October 2021; Global Voice, 25 August 2020). In April 2021, ACLED records the highest levels of violence against civilians in Haiti since coverage began in 2018. In particular, abduction events that month increased by approximately 250% compared to the previous month – two months before the constitutional referendum in June. The rise of kidnapping for ransom may have stemmed from gangs aiming to gather financial resources for their own ends or to support their political allies ahead of key elections (CARDH, 11 May 2021), such as the referendum. In spite of this, the number of kidnappings dropped during May and June, as the Village de Dieu and Grand Ravine gangs reportedly observed a truce period. Some allege the government paid the gangs to pause kidnappings to show that sufficient stability had been reached for the referendum to be held on 27 June (Le Nouvelliste, 10 May 2021).

The apparent truce did not, however, affect levels of armed clashes, with clash events peaking in June. The majority of recorded clashes took place between G-9 members and police forces. The increase occurred amid a series of fatal incursions targeting police stations, as G-9 members sought to seize law enforcement assets to support their operations (Reuters, 7 June 2021; RNDDH, 11 June 2021).

Conflicts between the G-9 gang coalition and other gangs that refused to join the alliance also reignited, leading to intensified clashes, especially in the disputed neighborhoods of Bel Air, Martissant, and Fontamara in Port-au-Prince (RNDDH, 7 April 2021). According to civil society members, some of these turf wars are politically motivated. Incursions of the G-9 gang alliance siding with the government in the Bel Air neighborhood – known as an opposition hotbed – may have been part of a wider government strategy to control dissident and strategic areas of the capital (RNDDH, 20 May 2021; Juno 7, 2 April 2021). Clashes between gangs continued to affect civilians, who were often caught in the crossfire and forcibly displaced (UNICEF, 15 June 2021).

Instability in Haiti culminated on 7 July with the killing of President Moise. In the immediate aftermath of the assassination, violence declined, with armed clashes involving gangs decreasing in July and August. The political power struggle that ensued (Reuters, 10 July 2021) likely pushed gangs to a period of observation as they tried to evaluate their prospects and that of their political allies.

While gang-related armed clashes fell following the assassination, ACLED records an increase in armed clashes between October and December. During this time, gang conflict intensified over control of key economic assets, such as the Martissant fuel terminal and roads connecting the southwestern regions with the capital and rest of the country (UNOCHA, 22 June 2021). The conflict led to fuel shortages, as the G-9 gang coalition blocked access to the fuel terminal and extorted fuel transporters (Associated Press, 25 October 2021). This significantly affected all sectors of Haiti’s economy, including healthcare (UNICEF, 25 October 2021), and ultimately led to a spike in demonstrations in October amid a nationwide general strike against insecurity and fuel shortages.

Rather than an unintended consequence of gang warfare, the blocking of the country’s key assets appears to have been part of a conscious effort by gangs to challenge the government’s authority. In October, Jimmy Chérizier, the leader of the G-9 coalition, declared an ultimatum, demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Ariel Henry in exchange for the end of the gang embargo on fuel resources (Haiti Libre, 27 October 2021). He later announced the lifting of the fuel embargo amid claims that it was orchestrated in collusion with members of the Tèt Kale party to destabilize Henry’s transitional government (Haiti Info Pro, 29 October 2021; Rezo Nodwes, 25 October 2021). The event demonstrated gang capacity to undermine the functioning of the country and to pressure the transitional administration.

Meanwhile, gangs also continued to target civilians during territorial disputes in order to assert their authority. Since the assassination of the president, levels of violence against civilians have steadily increased, peaking in November. Gangs also increased their demands for ransom to strengthen their resources, often targeting business owners, workers, or foreigners (RFI, 18 October 2021). Notably, compared to the first half of 2021, violence against civilians nearly doubled between July and December in Croix-des-Bouquets, a commune adjacent to Port-au-Prince controlled by the 400 Mawozo gang. Similarly, abductions also increased in the nearby district of Petionville, a wealthy and previously relatively safe enclave in Port-au-Prince, where politicians and business elites reside. The increase in violence in these areas is likely a consequence of the expansion of 400 Mawozo, indicating that some former tacit agreements between the ruling class and gangs may no longer apply in the post-Moise era.

What to watch for in 2022:

With the postponement of the constitutional reform and designation of general elections by the end of 2022 (Reuters, 28 September 2021), an end to Haiti’s political crisis seems a distant prospect. Ongoing instability will likely provide fertile ground for unrest and gang violence to continue in 2022. The transitional government has struggled to secure an agreement with the opposition on a path toward restoring political stability and addressing the intensification of gang activities (Alterpresse, 18 November 2021; Reuters, 17 October 2021). Meanwhile, some civil society actors and political parties have rejected the holding of general elections until security improves (Alterpresse, 2 August 2021; Alterpresse, 13 October 2021) and have even called for the formation of a new transitional government (Reuters, 4 February 2021).

The Haitian government’s inability to curb insecurity will continue to play into the interest of gangs. As gangs gain further power, they are likely to increasingly influence Haitian politics by providing support to political actors favoring their interests, or positioning themselves as a substitute to the state apparatus altogether. This has already been demonstrated with 400 Mawozo-imposed curfews in Croix-des-Bouquets, while G-9 leader Chérizier has presented himself as an official figure in national commemorations (The Guardian, 18 October 2021). More worryingly, 2022 opened with an assassination attempt on Henry organized by the Les Revolutionaires gang during Independence Day celebrations in Gonaives, Artibonite department on New Year’s Day (Le Monde, 4 January 2021). This is the second time in three months that Henry has been forced to withdraw from official celebrations under gang fire (The Guardian, 18 October 2021). Such attacks highlight the emboldening of gangs beyond Port-au-Prince and the government’s lack of authority before criminal and political opponents.

With key institutional reforms and elections yet to be organized for 2022, armed clashes between gangs will likely continue as they vie for power. New conflicts may also emerge, especially as the 400 Mawozo gang continues its territorial expansion in Port-au-Prince (Rezo Nodwes, 5 September 2021). Civilians will remain at risk as gangs seek to maintain or expand their financial resources during the political transition period. Meanwhile, sustained demonstrations are likely should high levels of violence against civilians persist unabated.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to all events coded with event type protests, as well as all events coded with sub-event type violent demonstration under the riots event type.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and 25 types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riots event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type and the excessive force against protesters sub-event type of the protests event type, as well as specific explosions/remote violence events and riots events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.