Latin America and the Caribbean experience many forms of political disorder:1 from insurgent groups vying for territorial control in Colombia and cartel violence fueling the rise of vigilantes in Mexico, to the suppression of dissent in Nicaragua and Venezuela. Yet even as each country’s disorder is shaped by factors unique to its local political landscape, the region also faces common threats. Gang activity stemming from drug trafficking is widespread, generating instability across El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Brazil, and more. In these countries, gang violence has risen to a point where it directly threatens public safety and security, and where gangs challenge the state for control of territory.2

Inequality and poverty have opened spaces for gangs to seize and consolidate power, in neighborhoods across the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince as well as throughout the favelas of Brazil. In cities like Brazil’s Rio de Janeiro, the security for local residents is further eroded by hybrid agents like ‘police militias’ who engage in violence that is often indistinguishable from the activity of local gangs.3

Around the region, civilians often face the brunt of disorder. They are targeted by gangs and cartels seeking to secure access to power and resources in Mexico and Honduras. Dissent and opposition are met with state violence in Nicaragua and Venezuela. And those protesting are often targeted with excessive and lethal force, as in Chile. Certain subsets of the population face even greater risk, such as indigenous communities in Chile and Brazil, and women in Colombia and Mexico.

Meanwhile, local populations increasingly take to the streets to voice their concerns through demonstrations and social movements, despite being met with repression and force. In Chile, a massive protest movement emerged after students rose up against rampant inequality; in Venezuela, supporters of opposition leader Juan Guaidó challenged the authority of President Nicolás Maduro; and Haiti remains under ‘lockdown’ after a spike in anti-government demonstrations.

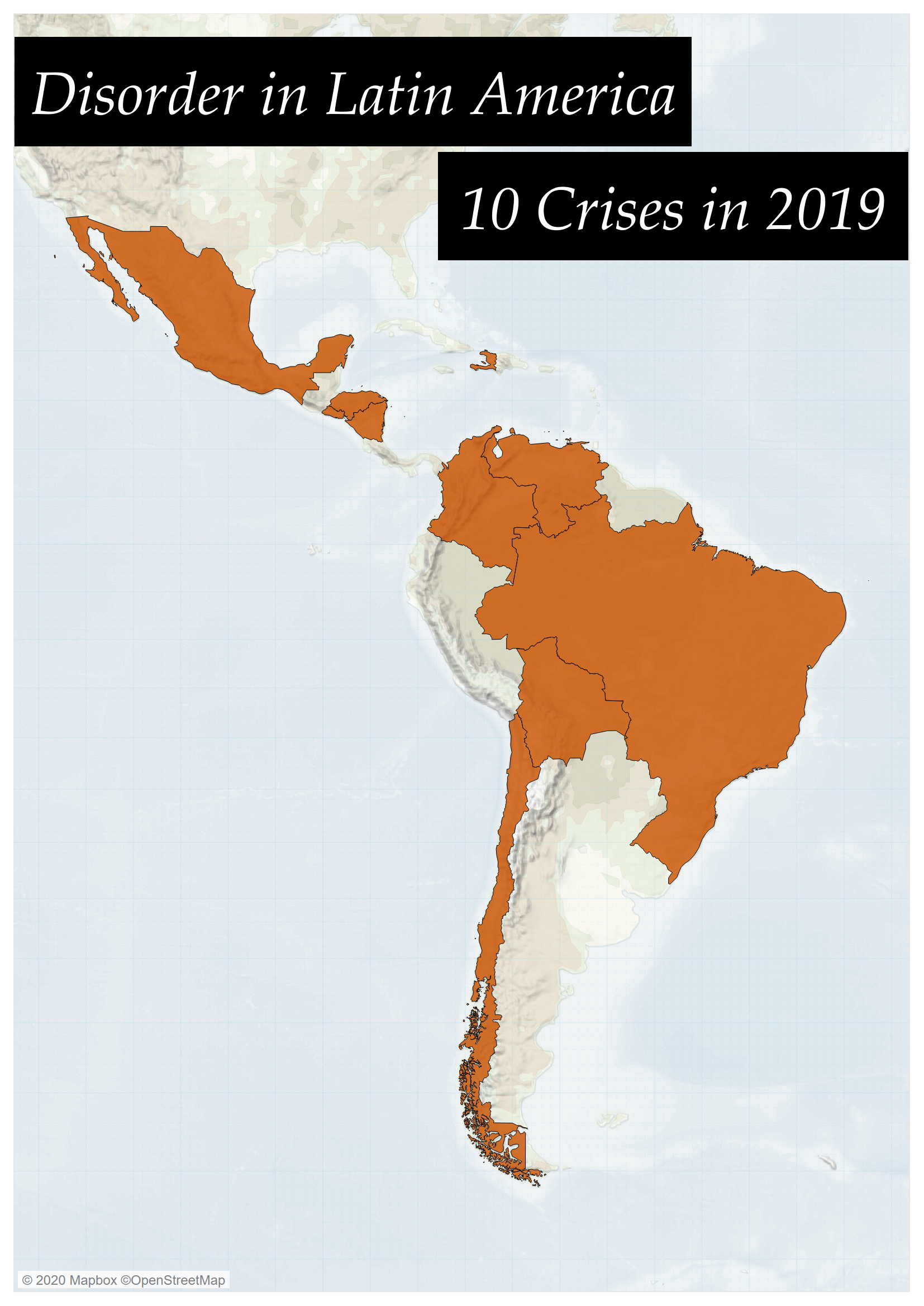

ACLED’s expansion of coverage to Latin America and the Caribbean allows for data-driven analysis of these trends in the region for the first time. In this report, ACLED has chosen 10 countries where disorder is widespread and evolving. It includes countries where cartel and gang violence is rampant — such as Mexico — as well as countries home to massive protest movements — such as Chile.

ACLED data for Latin America and the Caribbean are currently available from 2019 through to the present, with weekly updates allowing for real-time crisis monitoring across the region.

All data can be accessed through the Data Export Tool and Curated Data Files.

To access a full PDF copy of the report, click here.

To see analysis of specific situations, please click on the links below.

Disorder in Latin America: 10 Crises in 2019

Colombia

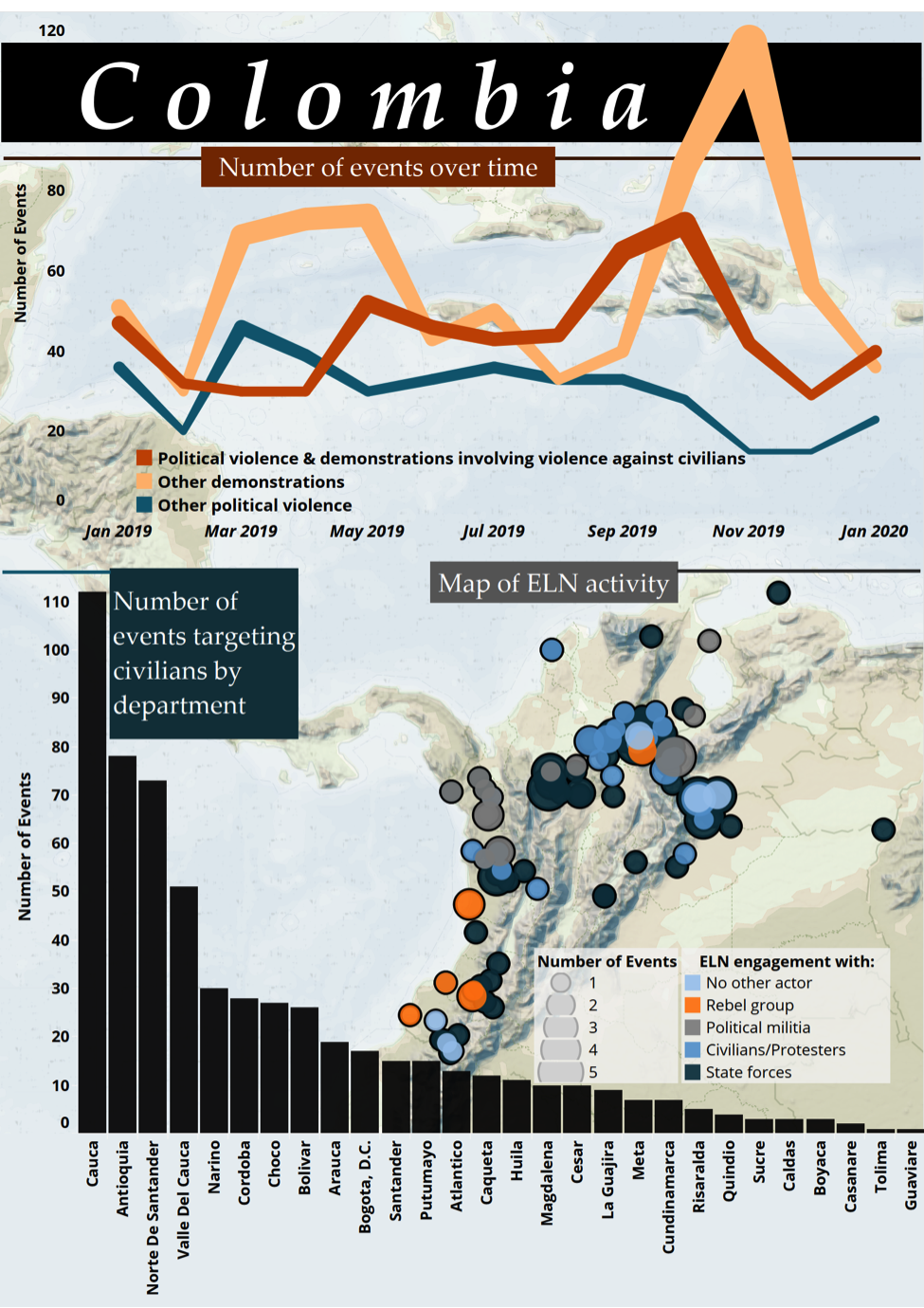

Three years into the implementation of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), now a legal political party known as the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force, political violence remains pervasive in Colombia. ACLED records more than 800 political violence events in 2019 as new territorial dynamics took shape across the country, with ongoing disputes between insurgent groups over territories formerly controlled by the FARC, as well as a growing number of attacks targeting social leaders and activists. ACLED also records more than 800 demonstration events in Colombia last year amid rising public discontent with the government of President Iván Duque.

Continued conflict between the state and the National Liberation Army (ELN) — the largest active insurgent group in Colombia following the FARC’s demobilization — has been a major driver of this violence. In January 2019, the ELN carried out a bomb attack on a police academy in Bogotá, leaving 22 police officers dead and 69 injured. Following the attack, the Colombian government officially withdrew from peace talks with the ELN. Clashes between the ELN and state forces account for approximately 30% of the more than 300 battles recorded by ACLED in Colombia last year. The group was especially active in the Norte de Santander, Arauca, and Chocó departments, where over half of all events involving ELN were reported. The group’s strong presence in the border region with Venezuela has also contributed to growing international tension between the two countries (see the infographic below).

The August 2019 announcement that former FARC leaders were withdrawing from the peace process to start a “new stage of fighting” has further complicated and destabilized the security situation (NPR, 29 August 2019). ACLED records over 120 political violence events involving FARC dissident groups in 2019, with the majority in the department of Cauca. Clashes have triggered the displacement of local communities, especially Afro-Colombians and indigenous groups (Insight Crime, 23 October 2019). The exact nature of the revived FARC guerrilla movement remains unclear, as does its relationships to other dissidents.

Although homicide rates have declined over the last decade (Insight Crime, 28 January 2020), Colombia continues to experience high levels of violence. In 2019, ACLED records over 800 fatalities across the country. The data show more than 400 attacks against civilians, and women were targeted in nearly 10% of these cases. Social leaders and activists are at particularly high risk: Colombia is one of the most violent countries in the world for human rights defenders (Front Line Defenders, 2020). Over 60 attacks targeting human rights defenders and activists were reported in 2019 alone. The majority of these cases occurred in the departments of Cauca, Antioquia, Bolívar, Caquetá, and Norte de Santander.

Political violence targeting civilians peaked in the months of September and October 2019, during the campaign for the first local elections featuring FARC, the former guerilla group, as a political party. Violence against human rights defenders in Colombia has received widespread attention from the international community (OHCHR, 10 May 2019) and has contributed to growing discontentment with the government of President Duque. These attacks were one of the driving factors behind the mass protests that swept the country in 2019.

Demonstrations account for a third of all disorder events recorded by ACLED in Colombia in 2019. In November, students, union members, teachers, and indigenous groups, among others, took to the streets to protest against President Duque and his proposed economic and political reforms (Al Jazeera, 27 November 2019). Protesters also raised concerns over corruption and recent economic policy decisions, in addition to demanding faster implementation of the peace agreement with the FARC.

With the peace deal under strain, 2020 is likely to be a challenging year for Colombia. The increased fragmentation of armed groups and their ongoing disputes over territory are expected to create new security challenges for the government of President Duque. Likewise, widespread discontent with proposed social and economic reforms may continue to foment unrest among many different sectors of society. The promise of national reconciliation made at the signing of the peace agreement remains unfulfilled.

For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of Colombia, see this methodology primer.

Venezuela

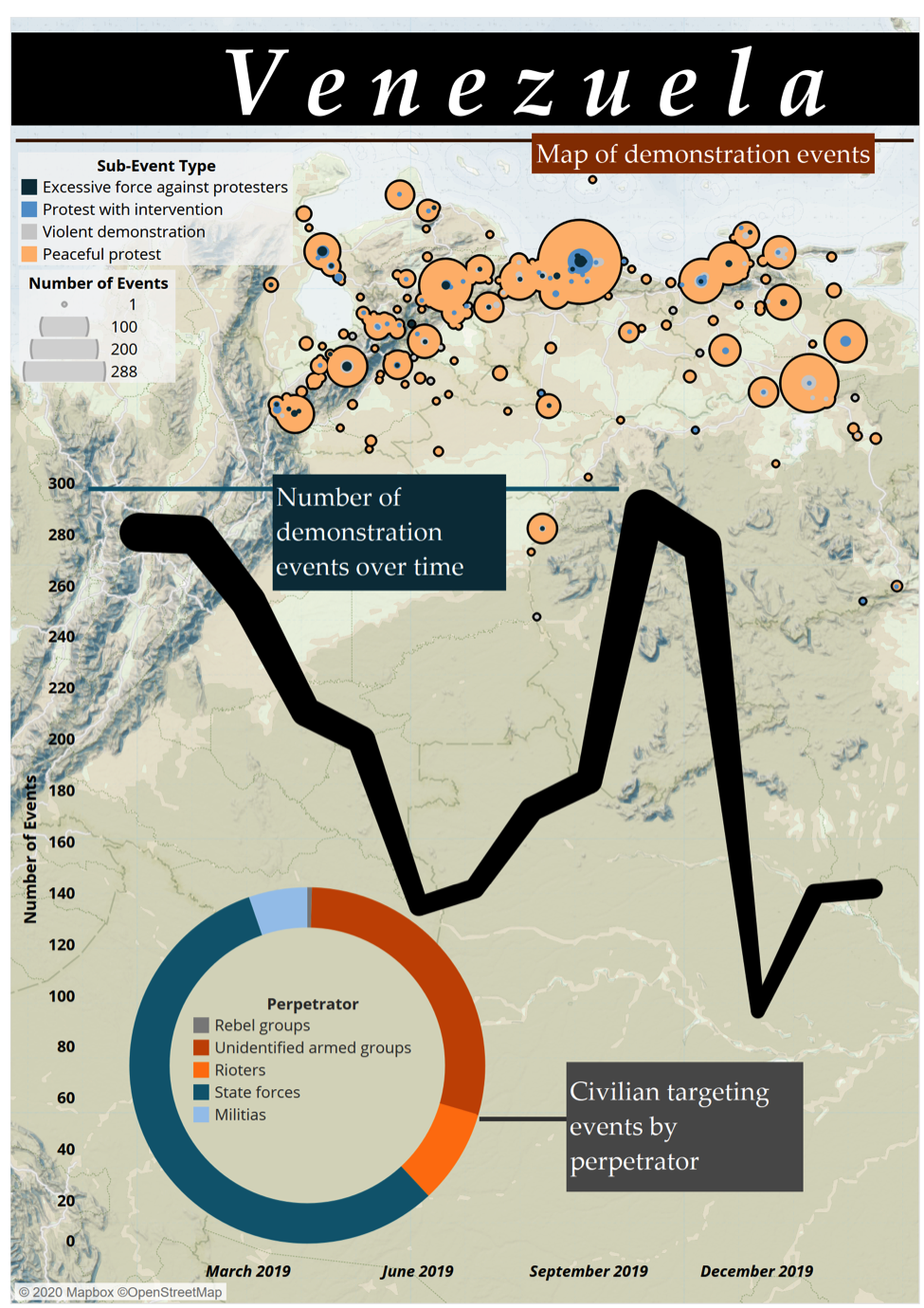

The lack of basic services including access to electric power, potable water, domestic gas, and gasoline fueled a political crisis in Venezuela in 2019. ACLED records over 3,000 disorder events nationwide in 2019, including more than 2,200 demonstration events, and the situation continues to deteriorate (see the infographic below). Most protests were peaceful, motivated by worsening living conditions, as food and medicine became increasingly scarce (Al Jazeera, 8 February 2019). Nearly half of all demonstrations occurred in Distrito Capital, Miranda, Anzoátegui, Bolívar, Lara, and Sucre.

Three specific developments contributed most to the heightened unrest: first, demonstrations were partly motivated by recurring electrical blackouts across Venezuela caused by failures in the country’s hydroelectric generation system in March and June 2019. Almost all 23 states experienced power outages (The New York Times, 8 March 2019). Second, in late January 2019, opposition leader and President of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, declared himself interim president, challenging the authority of President Nicolás Maduro and the legitimacy of the May 2018 presidential election. Guaidó’s call for new elections led to several demonstrations across the country in support of the opposition leader (see infographic). In April, the defection of a group of military officers further bolstered the opposition movement. Demonstrations peaked in the first half of 2019, when President Maduro refused entry to humanitarian aid at the height of the crisis. Third, the call for national strikes in October and November 2019 by health workers, teachers, and public sector workers contributed to heightened unrest (see infographic). These strikes were linked to labor claims, including respect for collective contracts and the dollarization of wages. Demonstrators blocked streets when the national government failed to respond.

Approximately 5% of all peaceful protests recorded in 2019 were met with intervention, and 2% were met with excessive force. In certain protests, the National Guard, the National Bolivarian Police, the Special Action Forces, and some state and municipal police officers used excessive force with the purpose of discouraging future demonstrations and marches (for example, see Reuters, 2 July 2019).

In addition to the violent crackdown against protesters, around half of all civilian targeting in Venezuela is perpetrated by state forces (see infographic). A third of all attacks on civilians are carried out by the Special Action Forces (FAES), an elite police unit created in 2017. Police allegedly reserve violence for individuals “resisting authority” (Reuters, 14 November 2019), but many observers report that security forces may be conducting extrajudicial killings targeting political dissidents ( OHCHR, 4 July 2019).

Several armed groups, including the Colombian FARC and ELN, are also present in Venezuela’s Zulia state, where nearly half of all battles in the country are reported. Both the FARC and the ELN have been active in Venezuela for decades, where they fight for territorial control and drug trafficking corridors.

Although more than 50 countries have recognized Guaidó as President of Venezuela (Global Americans, 10 December 2019), 2019 ended with the opposition struggling to regain momentum, while Maduro consolidated power. The ongoing lack of access to basic services and deteriorating living conditions will continue to drive Venezuelan migration to other South American countries. With parliamentary elections scheduled for the end of the year, the Venezuelan crisis will certainly persist into 2020.

For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of Venezuela, see this methodology primer.

Chile

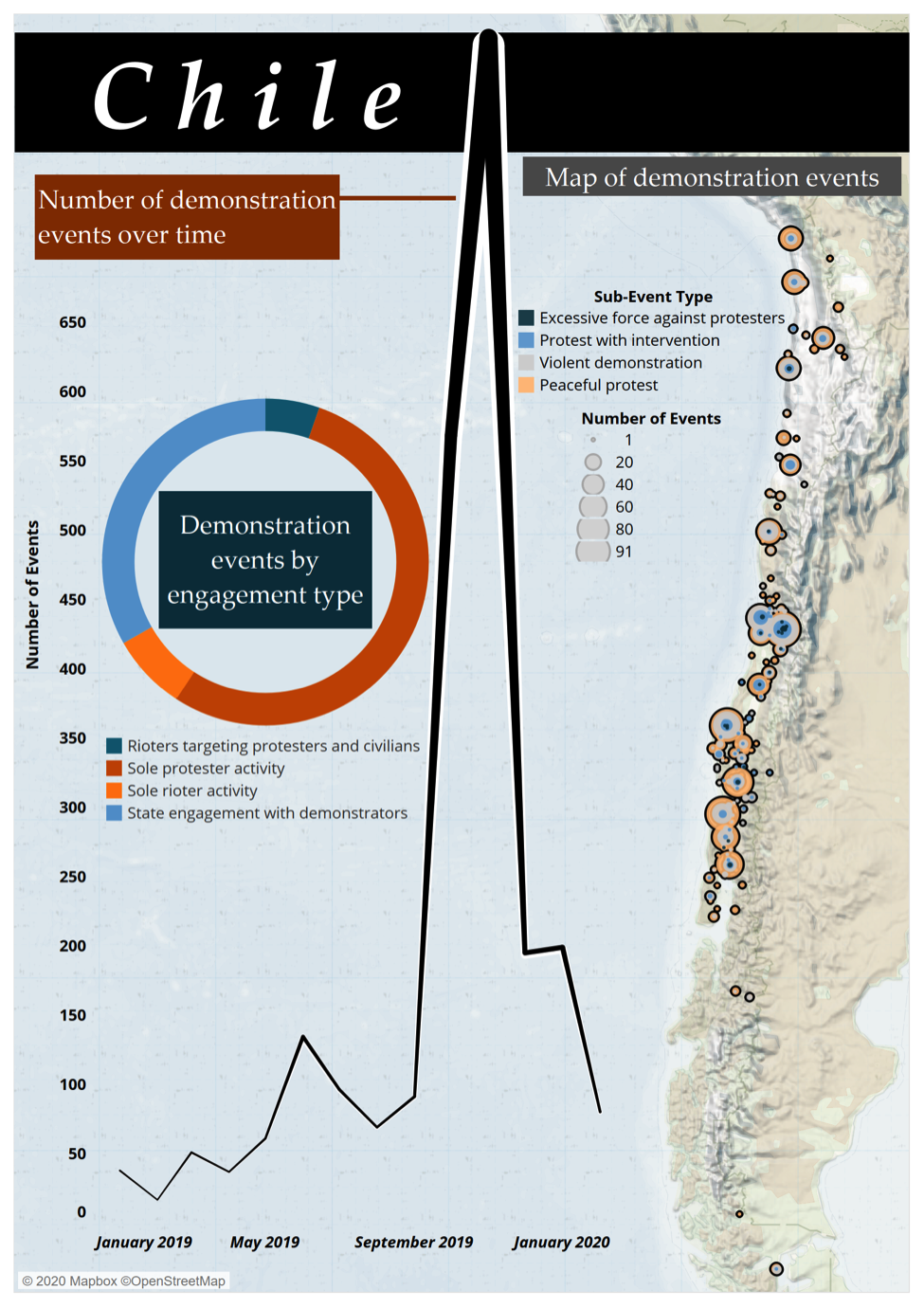

The government of President Sebastián Piñera weathered an unprecedented crisis in 2019. ACLED records over 2,800 disorder events in Chile over the course of the year, as several social organizations, indigenous groups, and trade unions held demonstrations against budget cuts for public services and other unpopular government policies. In October 2019, a hike in metro fares in Santiago prompted a series of protests led by student organizations (see the infographic below). The reportedly dismissive reaction of the government and the heavy-handed response by security forces (Reuters, 24 October 2019) resulted in mass demonstrations across the country, with protesters increasingly expressing broader demands for social equality and more political participation.

Many Chilean demonstrators rallied against low pensions and the high costs of education, healthcare, and utilities. During the last three months of the year, ACLED records more than 1,800 demonstration events, particularly in the Metropolitan, Valparaíso, Antofagasta, and Los Lagos regions (see infographic). By the night of 18 October 2019, President Piñera announced a state of emergency. For the first time since the end of the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in 1990, military forces were deployed to patrol the streets of the capital and other major cities. Citizens widely rejected the decision and defied the military curfew to continue protesting (Reuters, 19 October 2019).

Demonstrations against the government repeatedly turned violent, with groups of rioters looting private businesses and vandalizing public buildings. Violent demonstrations account for over 25% of disorder in Chile last year, while peaceful protests account for approximately 45% (see infographic). Nearly 40 fatalities were reported in 2019, the vast majority occurring during the height of the unrest in October and November. In late 2019, UN and independent human rights organizations documented multiple serious abuses committed by the national police and military forces (OHCHR, 2019; HRW, 2019; Amnesty International, 2019), including at least 405 reported cases of severe ocular trauma due to pellets fired by state security personnel. The organizations also documented cases of sexual violence and psychological torture, concluding that state forces had deliberately injured demonstrators to discourage them from taking part in protests (The Independent, 26 January 2020).

The crisis has had serious effects on the country, resulting in Chile’s withdrawal from hosting international events such as the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Trade Forum and the UN Climate Summit. It also prompted a cabinet reshuffle and a motion to condemn the Interior Minister Andres Chadwick (a cousin of President Piñera) over allegations of mismanagement related to human rights abuses committed by state forces (Reuters, 11 December 2019). Most importantly, to appease popular discontent, parliament passed a bill in December 2019 to enable a constitutional reform process, the first step of which will be a national plebiscite scheduled for April 2020 (Bío Bío, 18 December 2019).

The situation was exacerbated by an ongoing stalemate between the government and Chile’s Mapuche indigenous communities, which have demanded greater participation in the country’s institutions. In the regions of Araucanía and Biobío, native groups call for land rights protections and condemn the activities of forestry and logging companies in the area. Sometimes these demands turn violent: in January 2020, the Mapuche organization Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco (CAM) claimed at least six arson attacks since November 2019 (Biobio Chile, 23 January 2020).

With a new wave of demonstrations already recorded in the first months of 2020, civil unrest is expected to continue in Chile. With the highest disapproval rate of any president ever polled since the military regime (Reuters, 27 October 2019), Piñera and his cabinet face the challenge of tackling growing public discontent over established social and economic institutions. The beginning of the school year in March 2020 and the results of the constitutional plebiscite scheduled for 21 April will be crucial in the development of the current political crisis (DW, 21 January 2020). Student organizations are likely to continue demonstrating over corruption and low-quality public services throughout the year.

Bolivia

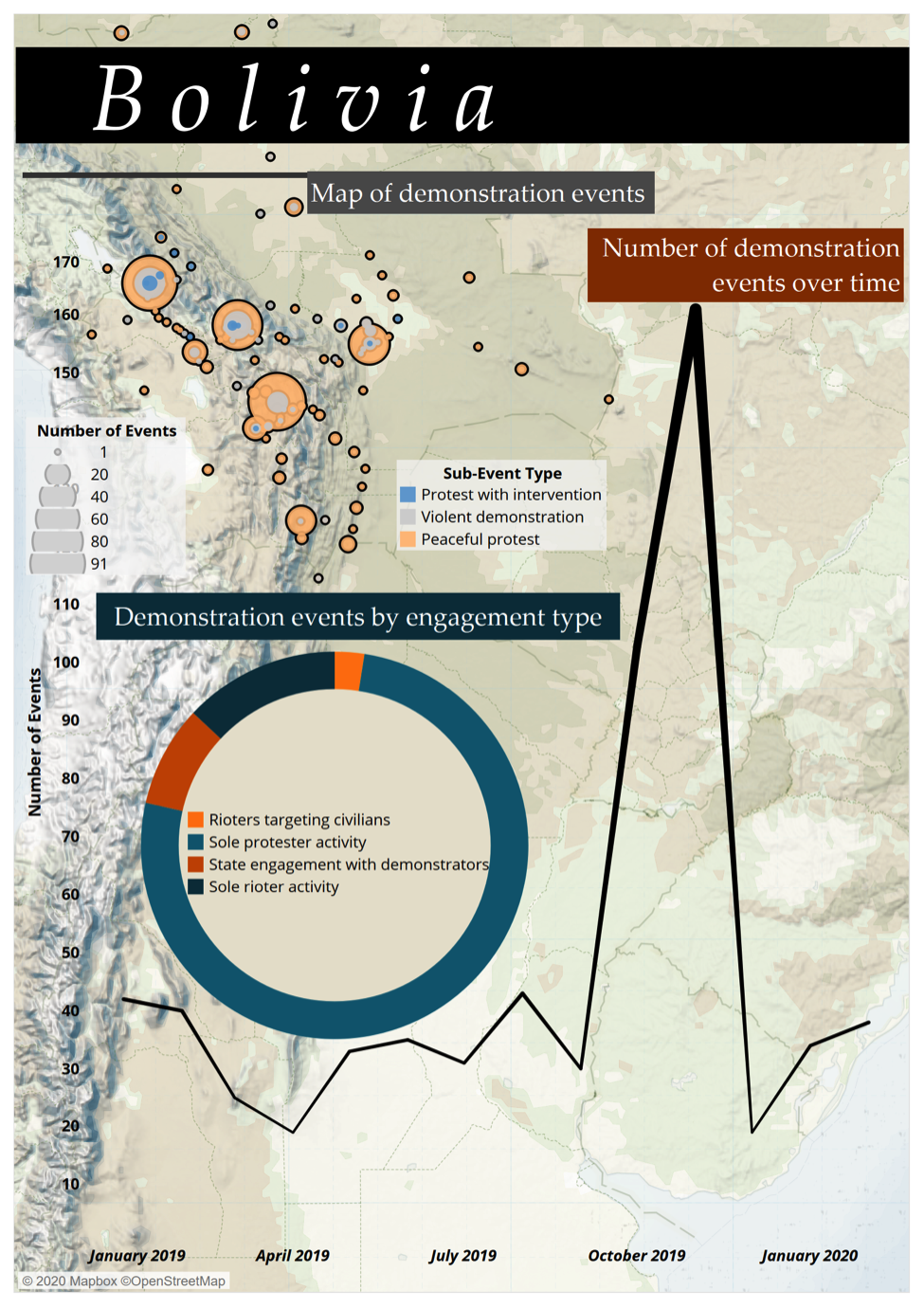

Bolivia was wracked by a major political crisis in 2019 when President Evo Morales resigned after 13 years in power following allegations of election fraud (BBC, 11 November 2019). The year was marked by demonstrations across the country, with peaceful protests accounting for approximately 70% of all disorder events. The main actors involved in these events include labor groups, farmers, health workers, and supporters of Evo Morales’ political party, Movement For Socialism (MAS). At the start of 2019, health workers demonstrated against the implementation of the Unique Health System (SUS), calling for additional resources for the social program. Labor groups also led demonstrations, demanding new contracts and additional work positions (see the infographic below).

Though 21 February 2019 marked the third anniversary of the 2016 constitutional referendum preventing Morales from running for a fourth term as president, a decision from the Supreme Election Tribunal (TSE) allowed his candidacy to move forward. Multiple demonstrations were held during the first half of the year against the TSE, with protesters calling for Morales to step down and respect the results of the constitutional referendum.

Between July and October, another wave of demonstrations emerged as forest fires broke out in different areas of the country, with residents and farmers calling on the government to take action to prevent damage to their property and crops.

Demonstration activity reached a peak after 20 October 2019, when the initial results of the presidential election pushed President Morales into the second round alongside former President Carlos Mesa, with a less than 10% difference in votes. After a 24-hour halt in vote counting, Morales was declared the winner. With reports of irregularities in vote counting, protests broke out demanding a new election process (OAS, 2019). After three weeks of demonstrations, Morales resigned and fled to Mexico on 30 November. From 20 October until Morales’ resignation, ACLED records almost 200 demonstration events in Bolivia, making up nearly a third of all disorder events reported in 2019.

Jeanine Áñez took over the presidency after several MAS politicians resigned, including Vice President Alvaro Garcia Linera; the President of the Senate, Adriana Salvatierra; and the President of the Congress, Victor Borda (La Razon, 10 November 2019). However, the rise of Áñez to the presidency led to a new round of demonstrations against the government. MAS supporters and indigenous groups feared the new right-wing administration would roll back social reforms and indigenous rights acquired during Morales’ presidency (The Guardian, 20 November 2019).

In the months of October and November 2019, the majority of demonstrations were reported in the regions of Chuquisaca, Cochabamba, La Paz, Santa Cruz, and Potosi (see infographic). Twelve people were reported killed during these demonstrations.

With new presidential elections scheduled for 3 May 2020, political disorder in Bolivia will likely remain high. Interim President Jeanine Áñez recently announced she will be running as a presidential candidate, while Evo Morales continues to influence Bolivian politics from abroad (Al Jazeera, 25 January 2020). These developments will likely lead to increased polarization in Bolivia’s already fractured society.

Brazil

Political polarization in Brazil has deepened under the new administration of President Jair Bolsonaro. The government has pushed major reforms, such as social security reform, labor reform, tax reform, and changes within the public security agenda, all of which provoked social unrest throughout 2019. With more than 10,000 political violence and demonstration events, Brazil accounts for nearly half of all disorder recorded by ACLED in South America last year.

In 2019, Brazil registered a consistent drop in the overall number of murders and violent deaths (G1, 16 December 2019), and this decline has been promoted by the federal government as a victory of the current administration. However, other factors can be attributed to this trend, including municipal and state public policies that were first implemented in 2018, before the start of the Bolsonaro government (Insight Crime, 23 September 2019).

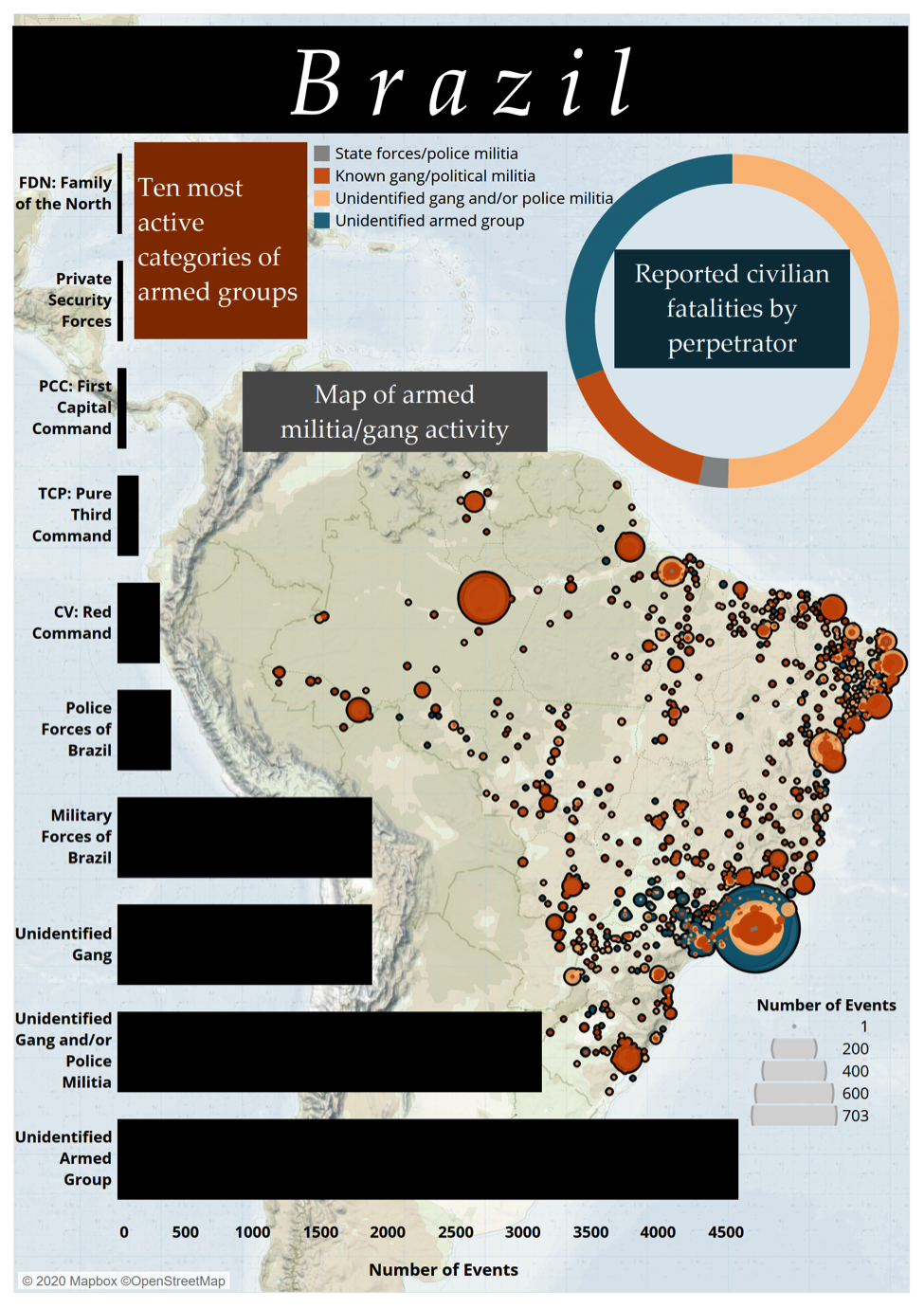

Armed violence remains a major security problem in Brazil’s main cities, where social inequality is pronounced, and the largest drug trafficking groups exercise significant control over areas in certain states. In the states of São Paulo and Paraná, the First Capital Command (PCC), the largest and most well-organized drug trafficking group in the country, has a monopoly on the crime market. Rio de Janeiro state, on the other hand, is the site of over half of all battles in Brazil, with multiple drug trafficking groups fighting for territory, including the Red Command (CV), the Pure Third Command (TCP), and the local Amigos dos Amigos (ADA). Rio de Janeiro used to be the historical stronghold of the CV, but is now home to a uniquely complex battleground that involves drug traffickers, state forces, and paramilitary groups (known as militias). The rates of activity of these groups can be seen in the infographic.

The militia groups in Rio de Janeiro state were created by former and serving police and military officers under the banner of fighting drug trafficking activities. Now present in several states, the police militias also offer the illegal provision of basic services through the collection of security fees, and often have connections with political authorities (El País, 29 January 2019). Violence perpetrated by narco gangs and police militias has become nearly indistinguishable, as both groups engage in corruption, extortion, and extrajudicial killing (The Guardian, 12 July 2018). Police militias often target civilians, community leaders, and human rights activists. The presence of narco militias — police militias operating drug selling points — further adds to the already complex landscape of criminal violence in Brazil (O Globo, 10 October 2019). A map of the activity of these armed militias and gangs can be seen in the infographic.

In northern Brazil, group fragmentation and the lack of one hegemonic gang makes criminal disputes particularly deadly. In 2019, more than 100 members of criminal groups were killed during internal clashes inside prisons in the northern states of Pará and Amazonas (Reuters, 29 July 2019). Recurrent prison massacres highlight potential shifts in criminal alliances across the entire country, which could lead to further clashes between different groups, including the PCC, which fights for dominance over the illicit market in Brazil (Insight Crime, 1 August 2019).

Gang violence significantly affects civilians in Brazil. ACLED records more than 1,400 attacks targeting civilians perpetrated by unidentified gangs and/or police militia groups in 2019 alone, with over 1,300 reported fatalities (see infographic).4 Police operations against criminal organizations also led to high levels of violence against civilians. State forces claim that criminal suspects use civilians as human shields, for example, yet witnesses report that police officers often use excessive force, attack and injure civilians, and block access for medical services. The number of civilians killed by military officers reportedly rose in 2019 (G1, 6 February 2020).

The first year of Bolsonaro’s administration was also marked by attacks against social leaders, activists, minorities, and indigenous groups. 2019 was the deadliest year for indigenous leadership in over a decade (G1, 10 December 2019). A proposed bill that would allow for more flexible implementation of extraction and energy projects in indigenous territories could increase land disputes, specifically in the northern states of Brazil, which are home to the Amazon forest (G1, 10 December 2019).

Territorial disputes between a growing number of militia groups and the fight for control between different drug trafficking gangs will likely lead to continued disorder in 2020. Political violence is expected to rise as municipal elections get underway in October. Meanwhile, social polarization will likely deepen as the administration continues to pursue pro-business environmental policies and dismiss minority rights (Al Jazeera, 7 February 2020), ensuring that 2020 is a disruptive year for Brazil.

For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of Brazil, see this methodology primer.

Mexico

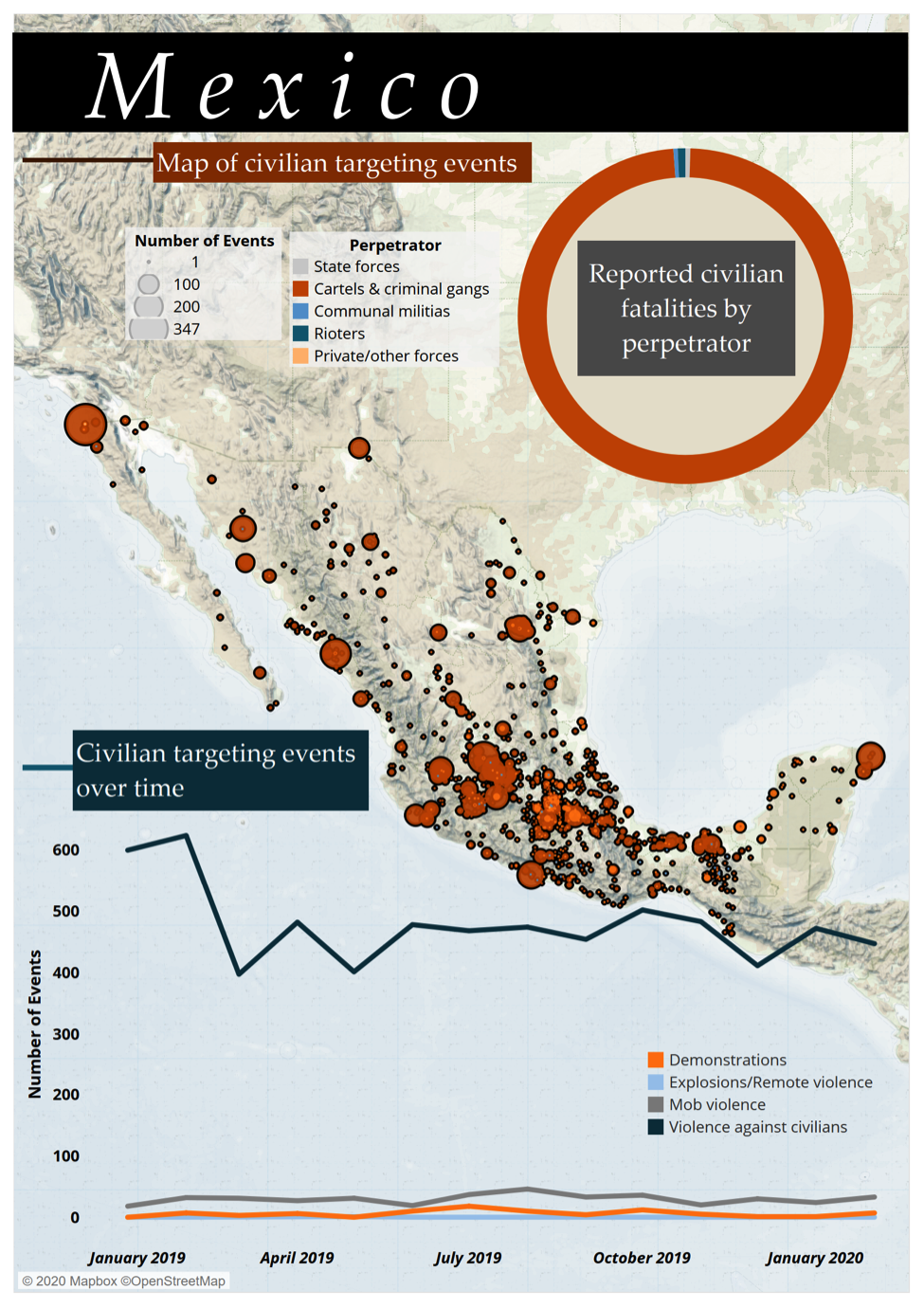

In 2019, fatalities in Mexico hit a record high, with the National System of Public Security (SNSP) documenting over 35,500 victims of intentional homicide and femicide (SNSP, 31 December 2019). ACLED records nearly 12,700 total disorder events in Mexico last year, and more than 9,200 fatalities from acts of political violence. Cartels and criminal gangs are responsible for the vast majority of the violence, and they continue to pose a grave threat to public security in the country. The response by the state (e.g. a crackdown on fuel theft; the creation of a National Guard), and the rise of local vigilante groups and communal militias to protect local communities, have offered no respite for civilians, who face attacks by all sides (these trends can be seen in the infographic below).

Cartel activities are becoming increasingly fragmented and diverse, hampering government efforts to reduce crime. When law enforcement cracked down on fuel theft, for example, the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel returned to the extortion of small businesses for income (Insight Crime, 15 November 2019). This is not an isolated case: ACLED records over 200 attacks targeting taxi drivers and small business owners in 2019. Cartels and gangs are also increasingly targeting local governments, whose representatives they view as valuable sources of information and political influence. Reports of assassinations of current and former mayors who either favor or hamper cartel activities are common. In 2019, more than 100 abductions and attacks targeted government officials and employees. For example, at the end of October 2019, the Mayor of Valle de Chalco in Mexico State was killed after publicly denouncing the Cartel de Tlahuac (Mexico News Daily, 31 October 2019).

Since 2006, there have been several attempts led by successive administrations to restore public safety – the most recent being the controversial creation of a National Guard by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2019. Their impact of such efforts remains to be seen: since the beginning of its operations, the National Guard has participated in fewer than 4% of armed clashes involving state actors and organized criminal groups. Rather, the National Guard has been primarily deployed as part of the Mexican government’s efforts to curb illegal immigration, in response to pressure from the US government. In June, 6,000 members of the National Guard were deployed to the border with Guatemala (DW, 7 June 2019) and in 2019, ACLED records 96 mass arrests with at least 2,400 migrants arrested.

In the absence of law enforcement, local communities increasingly rely on local militia groups to ensure their safety. Community policing is a phenomenon officially recognized in the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and San Luis Potosi. Self-defense groups and communal militias make themselves known through armed clashes with law enforcement agencies or through engaging in punitive acts against alleged criminals. Though these groups are ostensibly meant to ensure the security of the community, they occasionally target civilians, and add to the threats they face. Another consequence of insecurity and the lack of state response is the pervasiveness of lynchings targeting petty criminals: in 2019, there were over 330 cases of civilian lynchings by spontaneous vigilante groups, occurring principally in Puebla state, Mexico City, and Mexico state according to ACLED data.

Against this backdrop, citizens have held thousands of demonstrations calling for greater public safety and security. In total, ACLED records over 5,100 demonstration events across Mexico in 2019, including nationwide protests against gender-based violence in March, August, and November.

At the same time, reporting on disorder has become more challenging. In 2019, 52 instances of violence against journalists were recorded by ACLED, making Mexico one of the most dangerous places to work as a journalist.

Looking forward, Mexico will continue to face significant challenges to safety and security in 2020. The walls between the cartels, the judiciary and executive institutions are growing thinner, while those separating Mexico from its neighbors grow thicker. Important institutional reforms are necessary to tackle the pervasiveness of cartel violence. The state’s focus should be on evolving tactics and modes of operation to meet the increasingly complex constellation of threats across the country, especially as smaller criminal groups continue to sprout and join the fray. As it is, Mexico is a long way from the “Peace and Happiness” promised by President Obrador in his 2020 New Year’s speech.

For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of Mexico, see this methodology primer.

Nicaragua

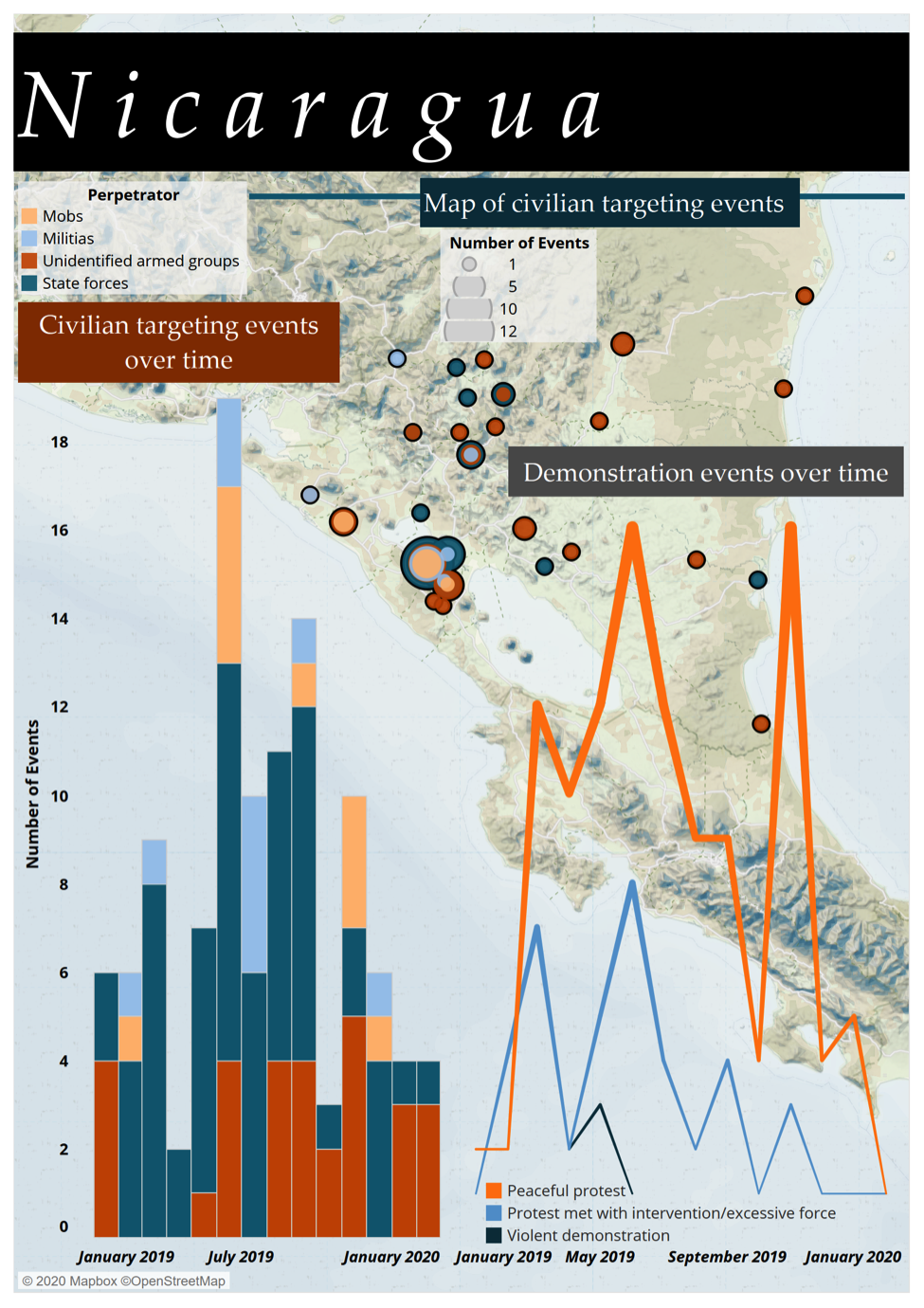

The Nicaraguan government’s deadly crackdown on dissent ignited a political crisis in 2018, culminating in a protest movement that persisted into 2019. The authoritarian regime of President Daniel Ortega continues to fuel anti-government demonstrations by repressing democratic space.

State and pro-government forces are deployed to monitor, threaten, harass, and detain dissidents in Nicaragua. Still, despite an intense police presence aimed at deterring protests (OHCHR, 2019), 60% of approximately 240 disorder events recorded across the country in 2019 are demonstrations, mostly taking place in the capital, Managua. In nearly 30 of these events, state forces intervened and dispersed, arrested, or intimidated protesters (see the infographic below). With severe restrictions on free assembly, protests have increasingly shifted from public spaces — such as streets and the front of national institutions — to private spaces like Catholic churches, universities, and shopping malls. The dismantling of institutional checks on presidential power (Human Rights Watch, 2019) and the government’s crackdown on dissent are major drivers of the protest movement.

Talks between the government and opposition throughout 2019 resulted in the release of 492 political prisoners detained during the protest wave of 2018 (OHCHR, 2019). Amid growing national and international pressure, a second release took place on 30 December 2019, freeing another 91 demonstrators. Among the released was human rights defender Amaya Coppens, the leader of the main student organization behind the protests, the 19th of April Student Movement.

In addition to suppressing demonstrations, state forces, as well as anonymous or unidentified groups, directly target opposition leaders (see infographic). Attacks on opposition figures by armed pro-government groups led to over 20 reported fatalities in 2019, according to ACLED data. For example, on 23 January 2019, in El Cua, Jinotega, a member of Citizens for Freedom was shot dead, with reports that police officers were among the attackers. On 18 July 2019, two people — including a well-known opponent of the government — were killed in Nueva Segovia department by unidentified armed individuals.

State repression also targeted the press in 2019: ACLED records at least five attacks against journalists or media outlets that have publicized reports critical of the government or President Ortega.

With political dialogue at a standstill, the crisis in Nicaragua has persisted into 2020. Demonstrators have witnessed concrete results stemming from continuous national and international pressure on the government, however, with two waves of political prisoner releases in 2019. The last release in late December may galvanize the protest movement, with demonstrations continuing into the early months of 2020. As presidential elections approach in 2021, election reform will remain a key issue for Nicaragua, with a renewed sense of urgency for the opposition.

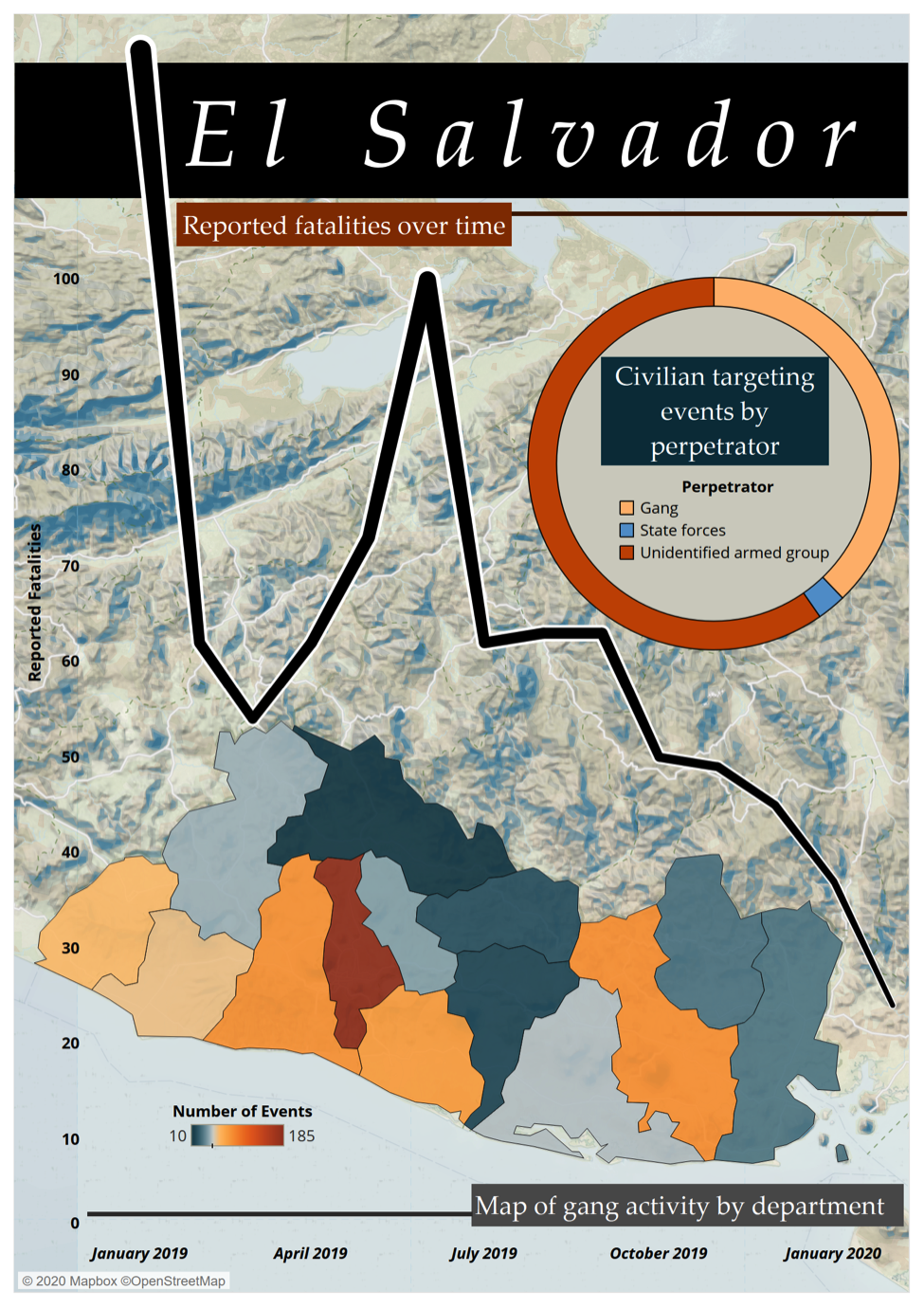

El Salvador

In El Salvador, 2019 ended with a significant drop in reported homicides (see the infographic below). The government announced a more than 30% reduction in the homicide rate in comparison to 2018, from 50 to 37 murders per 100,000 residents (EFE, 23 December 2019). The administration of President Nayib Bukele, who took office in June 2019, has moved to implement a security policy focused on state action to fight criminal gangs and reduce homicide rates. However, despite this reduction, ACLED data show that El Salvador remains one of the most violent countries in Central America.

Civilian targeting makes up over 40% of all disorder reported across El Salvador in 2019, followed by armed clashes — primarily between gangs known as ‘maras’ and state forces — at 35%. The widespread presence of gangs also leads to frequent disputes between criminal groups over the control of territory. Despite the declining homicide rate, gangs remain dominant in many areas. According to ACLED data, gangs are active in all 14 departments in El Salvador (see infographic), and they perpetrate more than 95% of all violence targeting civilians. Attacks on civilians are especially deadly: at least half of all reported fatalities stemming from political violence in the country are civilians. Residents of neighborhoods controlled by gangs face constant threats and must avoid crossing ‘invisible borders’ established by criminal groups (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 27 December 2019). Although there are many local gangs active across the country, Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and the groups of Barrio 18 (B-18) remain the strongest maras, participating in at least 25% of all armed clashes in 2019 (International Crisis Group, 26 November 2018).

On 20 June 2019, President Bukele launched a new security program known as the “Territorial Control Plan,” seeking to bolster the ability of state forces to confront criminal gangs, regain control of territory, and introduce strict supervision over prisons. Authorities have attributed the unprecedented drop in homicides over the last five months of 2019 to this approach (Univision, 2 January 2020). However, human rights organizations have criticized abuses reportedly perpetrated by police officers during these security operations, such as excessive force and extrajudicial executions (Human Rights Watch, 8 December 2018; Insight Crime, 4 October 2019).

Contradicting the government, opposition leaders and security experts suggest that the reduction in violence could be related to agreements between MS13 and B-18, rather than the state’s security policy (Univision, 25 August 2019). In the past, the ‘truce’ that was arranged between the maras — which was recognized by the government from 2012 to 2015 — helped to generate a similar reduction in the homicide rate (Interpeace, 2013). This measure was not without controversy, however, due to the political implications of direct negotiations between the government and criminal gangs. Currently, there are no formal negotiations around a ‘truce’ between Bukele’s government and the gangs, though observers have not ruled out the possibility (The Washington Post, 31 October 2019).

No matter the root cause of the declining homicide rate, ACLED continues to record high levels of gang violence in El Salvador, and criminal groups continue to exercise significant territorial control. The current administration’s response may produce short-term results, but more needs to be done in order to generate sustainable reductions in violence. Ongoing disputes over the approval of a loan to fund the third stage of President Bukele’s plan illustrate how the political debate over the country’s security situation will continue to impact disorder trends in 2020.

ACLED codes gang violence in contexts where it meets a threshold in which (1) public safety and security are at stake, (2) gang(s) hold de facto control of at least subregions of the state, and (3) gangs perpetrate very public acts of violence. In this way — challenging the state monopoly on power, territorial control, and use of terror tactics — gangs are viewed as akin to actors engaging in political violence, and as such, their activity is coded in these contexts. El Salvador is one of these countries. For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of gang activity in the region, see this methodology primer.

Honduras

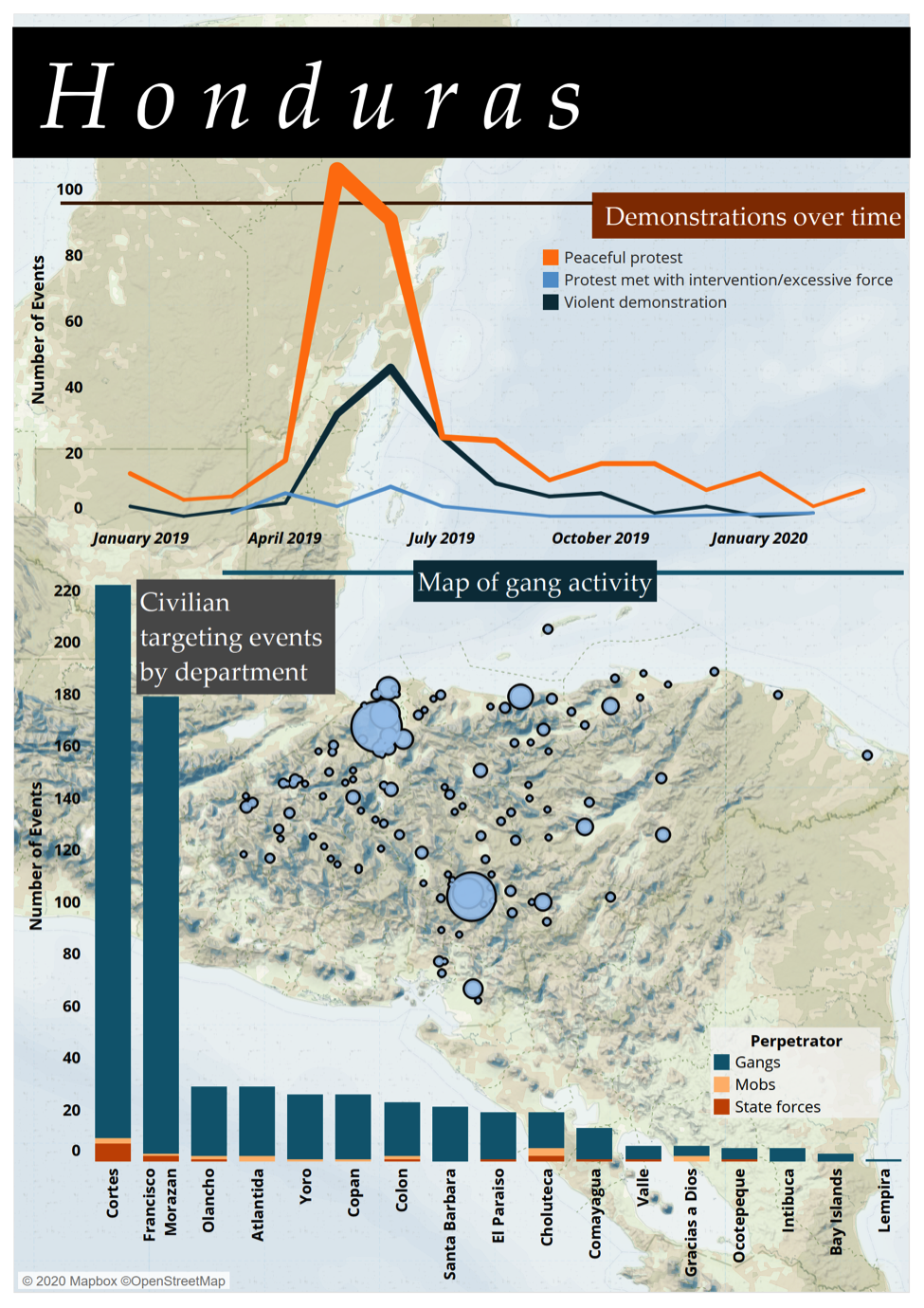

In 2019, the disorder landscape in Honduras was dominated by social protests and gang violence targeting civilians. While Honduras has one of the highest rates of economic growth in Latin America, it simultaneously suffers from some of the worst levels of inequality and poverty in the region. Its strategic geographic location in the center of Central America, with coastal access to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, is a boon for both licit and illicit economic activity, making it a key hub for drug trafficking. The resulting violence has had a major impact on the country’s stability and security.

Outside observers as well as Honduran civil society have increasingly raised concerns that the country is at risk of becoming a narco-state (DW, 27 October 2019; BBC, 7 August 2019). In 2019, state forces seized over 20 clandestine airstrips likely involved in the drug trade, and the recent conviction of President Juan Orlando Hernandez’s brother, Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernandez, on drug trafficking charges by a US court in October 2019 has further contributed to the perception that drug crime is pervasive in the country. As a consequence, opposition parties led a series of demonstrations at the end of 2019, calling for a peaceful uprising.

ACLED records 1,200 political violence and demonstration events in Honduras in 2019, over 40% of which are civilian targeting events. More than 90% of these attacks are perpetrated by criminal gangs and anonymous or unidentified armed groups, resulting in nearly 600 reported fatalities (see the infographic below). The departments with the highest rates of civilian targeting in 2019 are Francisco Morazan and Cortes. Of identified gangs, Barrio-18 (B-18) and Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) pose the greatest threat due to their territorial presence, size, and activity.

Transportation workers, especially taxi and bus drivers, are particularly vulnerable to extortion and other types of violence as their occupation requires them to traverse gang-controlled territory. Criminal groups regularly target these workers, forcing them to pay a so-called “war tax” or face the risk of death. So many killings were reported in 2019 that demonstrators took to the streets calling on the state to protect transportation workers from gang violence, and take action to end extortion by local armed groups.

Demonstrations account for approximately 40% of all disorder events recorded in Honduras last year. Nationwide, mass demonstrations erupted in April after the government announced reforms to the country’s health and education systems (see infographic). Protesters feared these changes would lead to privatization and mass layoffs. Though the reforms were eventually withdrawn by the government, protests continued over corruption and impunity. More than 60% of demonstration events between March and July 2019 were peaceful and did not face intervention. However, state forces engaged with demonstrators in nearly 25% of events, attempting to disperse them with tear gas or rubber bullets. In some cases security forces used live ammunition. The violent crackdown resulted in at least six fatalities.

The year ended with clear challenges for security and political stability in Honduras. If the government fails to address corruption, inequality, drug trafficking, and gang violence, the country will continue to face severe disorder.

ACLED codes gang violence in contexts where it meets a threshold in which (1) public safety and security are at stake, (2) gang(s) hold de facto control of at least subregions of the state, and (3) gangs perpetrate very public acts of violence. In this way — challenging the state monopoly on power, territorial control, and use of terror tactics — gangs are viewed as akin to actors engaging in political violence, and as such, their activity is coded in these contexts. Honduras is one of these countries. For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of gang activity in the region, see this methodology primer.

Haiti

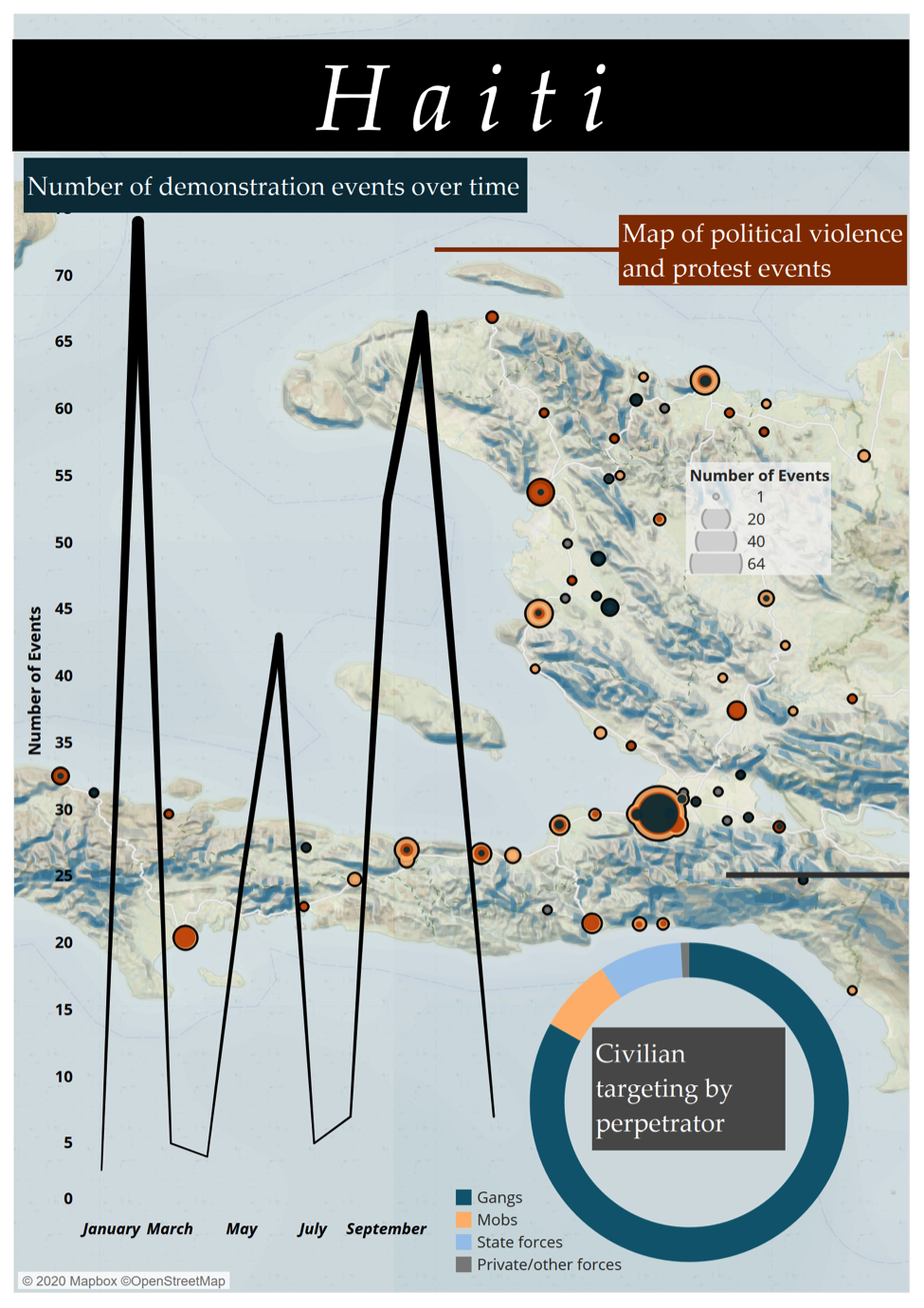

2019 was another turbulent year for Haiti. The poorest country in the Americas is still struggling to recover from the 2010 earthquake that devastated its already fragile infrastructure. Haiti’s disorder landscape is shaped by unstable institutions, corruption, high inflation, extreme poverty, gang violence, and lack of access to food, water, and fuel.

Of the over 500 disorder events recorded by ACLED in Haiti last year, 64% are demonstrations. Protests over rising fuel prices in 2018 continued and accelerated in 2019, soon transforming into more general anti-government demonstrations (see infographic). Protesters demanded the resignation of US-backed President Jovenel Moise, who took office in 2017 after an election marred by irregularities and less than 25% voter turnout. In the years since, Moise has faced accusations of corruption and mismanaging funds for social programs, and in July 2019 he appointed the country’s fourth Prime Minister in two years after the third failed to reach consensus in Parliament and resigned within three months.

During the anti-government demonstrations, rioters set up barricades, burned tires, threw rocks, and in some cases set fire to houses and cars. Police intervened with teargas and, on several occasions, fired live ammunition at demonstrators. Clashes between state forces and demonstrators resulted in at least 58 reported fatalities in 2019, if not more. In September alone, at least 17 people were killed and 189 injured (Haiti’s National Network for the Defense of Human Rights, 3 October 2019). While it is unclear who opened fire and who was killed in some cases, most fatalities were either demonstrators or other civilians, such as journalists (Committee to Protect Journalists, October 1, 2019).

The standstill caused by the public uprising is known in Haitian Creole as peyi lok, meaning “country lockdown.” Many public services have been canceled, and public safety is at risk. Schools were closed for most of the fall semester, hospitals and emergency services are limited, transportation has been cut off, and businesses have shut down.

At the same time, gang violence remains a serious threat, particularly in impoverished neighborhoods such as Cité Soleil and Village de Dieu in the capital, Port-au-Prince (see infographic). Unidentified armed groups, including gangs, often engage with police officers. The majority of armed clashes recorded by ACLED in Haiti are between unidentified armed groups, resulting in 63 reported fatalities. Civilians are often caught in the crosshairs as well: at least 95 civilian fatalities are reported in 2019, largely killed in attacks perpetrated by unidentified armed groups and gangs (see infographic). A third of all civilian targeting events take place in Port-au-Prince city. More generally, ACLED records most civilian targeting events in Ouest department, which includes the capital as well as a large portion of the border with the Dominican Republic.

While many schools and businesses reopened in December 2019, the crisis remains unresolved. In view of political dysfunction, rampant gang violence, and increasing popular discontent, it appears that the country is approaching a deeper crisis that is unlikely to be resolved soon, raising the possibility of intensified unrest throughout 2020.

ACLED codes gang violence in contexts where it meets a threshold in which (1) public safety and security are at stake, (2) gang(s) hold de facto control of at least subregions of the state, and (3) gangs perpetrate very public acts of violence. In this way — challenging the state monopoly on power, territorial control, and use of terror tactics — gangs are viewed as akin to actors engaging in political violence, and as such, their activity is coded in these contexts. Haiti is one of these countries. For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of gang activity in the region, see this methodology primer.

____________________

Notes

1 The term disorder is used in this report to refer to all political violence and demonstrations. This effectively includes all events in the ACLED dataset, minus Strategic developments — which should not be visualized alongside other, systematically coded ACLED event types due to their more subjective nature. For more on Strategic developments and how to use this event type in analysis see this primer.

2 In this way — challenging the state monopoly on power, territorial control, and use of terror tactics — gangs are viewed as akin to actors engaging in political violence, and as such, their activity is documented in these contexts by ACLED. For more on ACLED methodology around the coverage of gang violence, see this methodology primer.

3 The police militia (milícias) groups of Rio de Janeiro state were created by former and serving police and military officers under the banner of fighting drug trafficking activities. Now present in several states of Brazil, they have extended their domain to the illegal provision of basic services and the collection of security fees. Violence perpetrated by narco gangs and police militias has become nearly indistinguishable, as both groups engage in corruption, extortion, and extrajudicial killing (The Guardian, 12 July 2018). The semi-recent development of narcomilícias – police militias operating drug selling points – further adds to the already complex landscape of criminal violence in Brazil (O Globo, 10 October 2019). For more on ACLED coding methodology in coverage of Brazil, see this methodology primer.

4 Traditional media coverage of inter-city shootouts is often lacking details on who exactly is involved in each event. This has given rise to citizen-led ‘new media’ solutions. The most popular of these, Onde Tem Tiroteio (OTT), is an app created to help locals in Rio de Janeiro track shootouts in real-time, thus avoiding the crossfire. OTT uses a network of trusted informants throughout the city and sends alerts of confirmed shootouts to millions of people a day via different social media platforms (Clarin, 6 July 2017). ACLED reviews OTT reports on a daily basis. While OTT reports are often even more vague on details than traditional media – their focus being on reporting immediate danger rather than analysis – the use of OTT as a source creates a more complete picture of violence in urban centers, even if the result is a high number of events involving unidentified agents. For more on ACLED coverage of Brazil, see this methodology primer.