Far-Right Violence and the American Midterm Elections

Early Warning Signs to Monitor Ahead of the Vote

3 May 2022

This report tracks the evolution of far-right activity in the United States from the start of ACLED coverage in 2020 through the first quarter of 2022, with a view toward trends to watch going into the midterm elections in November. All data are available for direct download here. Definitions and methodology decisions are explained in the US coverage FAQs and the US methodology brief. For more information, please check the full ACLED Resource Library.

Scroll down to read online

Executive Summary

A narrow focus on aggregate trends in political violence can obscure important new patterns and warning signs. While the total number of political violence events in the United States declined in 2021 after far-right groups stormed the Capitol at the start of the year, trends since then reflect an ongoing evolution in anti-democratic mobilization on the right — not the aftermath of its high-water mark. Many of the same far-right groups and networks involved in the Capitol attack have adapted their activity to fit the new environment. These adaptations have manifested in multiple ways: the landscape of actors has become more defined; demonstration engagement has shifted, with a focus on protests that allow for the co-option of new supporters; some actors, like the Proud Boys, have increased their use of violence; armed protests have proliferated, particularly at legislative facilities; contentious counter-demonstration trends have intensified; offline propaganda and vigilantism is on the rise, especially motivated by white supremacy and white nationalism; and preparatory actions have surged, including recruitment drives and training exercises.

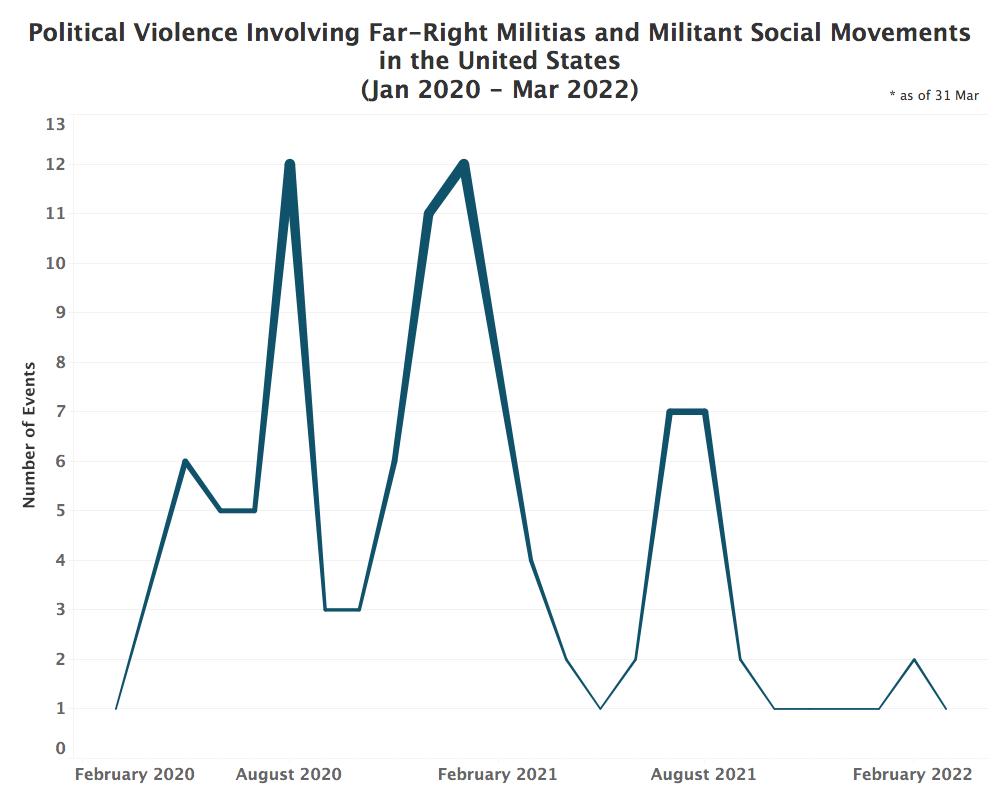

ACLED data indicate that political violence in the United States, and specifically violence involving far-right militias and militant social movements, typically manifests in peaks and lulls. Against this backdrop, the recent decline in aggregate events should not be taken as a sign that the threat of violence has abated. On the contrary, current trends indicate that it may only represent a relative calm before the next storm.

The United States faces many latent risks, and a wide range of factors that can contribute to and elevate these risks — from the ascendance of extremist protest drivers like white supremacy and white nationalism, to the increased rate of armed demonstrations at statehouses, to a rise in militia training and recruitment campaigns — are intensifying. Monitoring these factors, and these groups, will be critical for detecting emerging threats, particularly in the lead-up to potential flashpoint events, such as this year’s midterm elections.

Key Findings

While the total number of active far-right militias and militant social movements (MSMs) declined last year, many groups actually increased their activity and influence. Some of the most active and violent groups, like the Proud Boys, have only become more active and more violent: Proud Boys activity rose by 15% overall in 2021, and the group’s engagement in violent demonstrations rose by 57%. Approximately 25% of all demonstrations involving the Proud Boys turned violent in 2021, relative to 18% in 2020. Militias and MSMs are also increasingly engaging in right-wing demonstrations more broadly, generating recruitment and coalition-building opportunities within the wider right-wing activist network but also amplifying the risk of violence: when militias and MSMs are involved in right-wing demonstrations, the events are 12 times more likely to turn violent or destructive.

Despite the heightened threat of violence, law enforcement intervention in demonstrations involving far-right groups continued to decrease. Demonstrations involving far-right militias or MSMs turn violent over 11% of the time — approximately twice as often as demonstrations in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, by comparison — but they have been met with an increasingly limited police response. In 2020, authorities engaged in 8% of all demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs, and in 2021 this figure dropped to less than 7%. So far in 2022, police have engaged in less than 5% of all demonstrations involving far-right militias or MSMs.

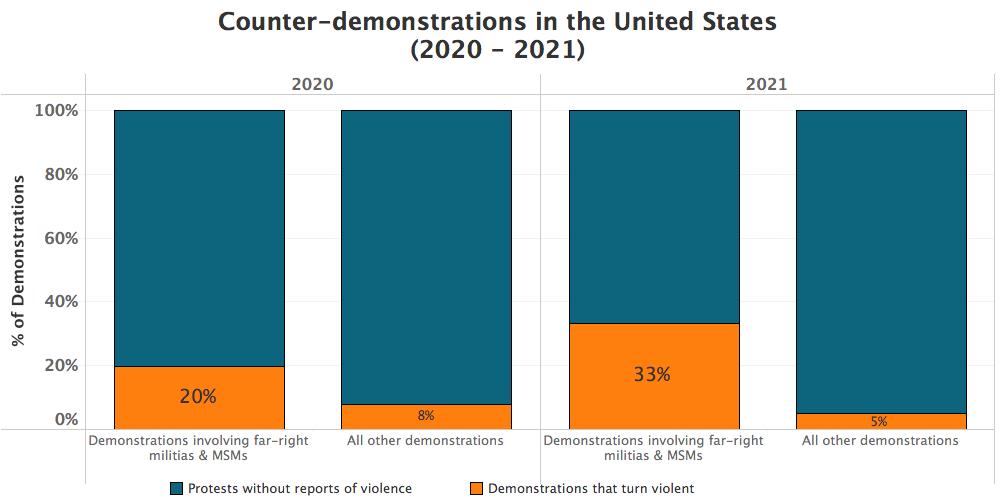

Counter-demonstrations (involving two opposing groups) have become more violent, and the risk that violence will break out is even higher if far-right militias and MSMs are present. Overall, counter-demonstrations turn violent or destructive five times as often as demonstrations that proceed unopposed, and the rate of violence has increased over time. This rate, and increase, is even higher for counter-demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs. In 2021 a third of all counter-demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs turned violent or destructive, up from a fifth in 2020.

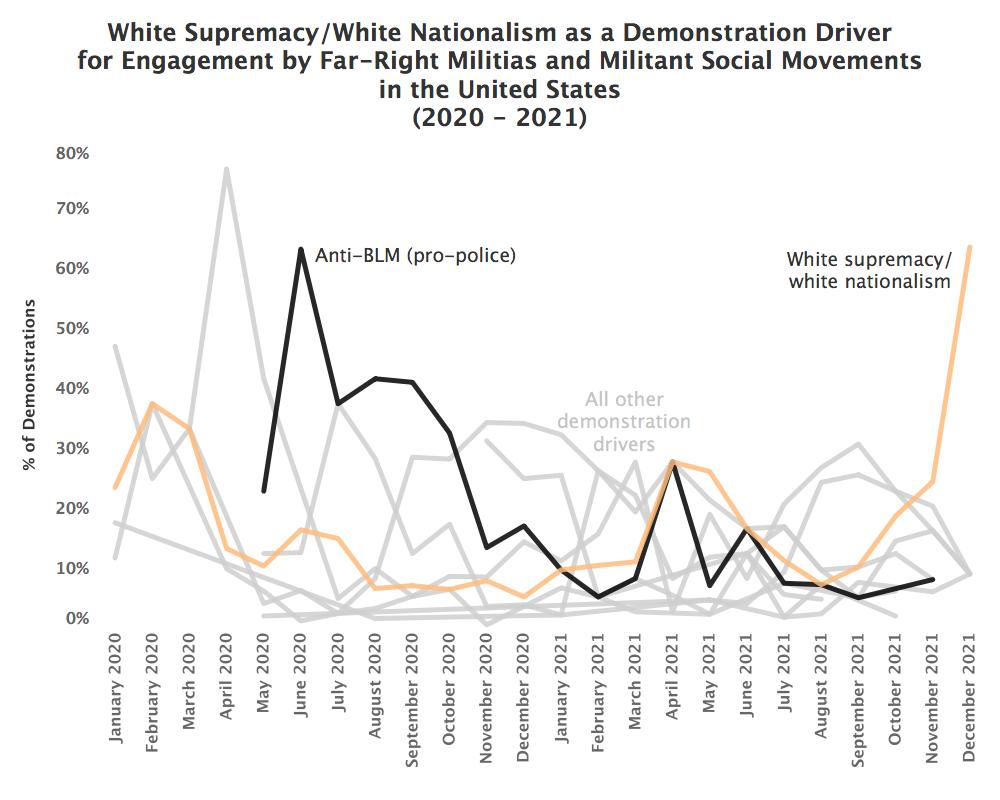

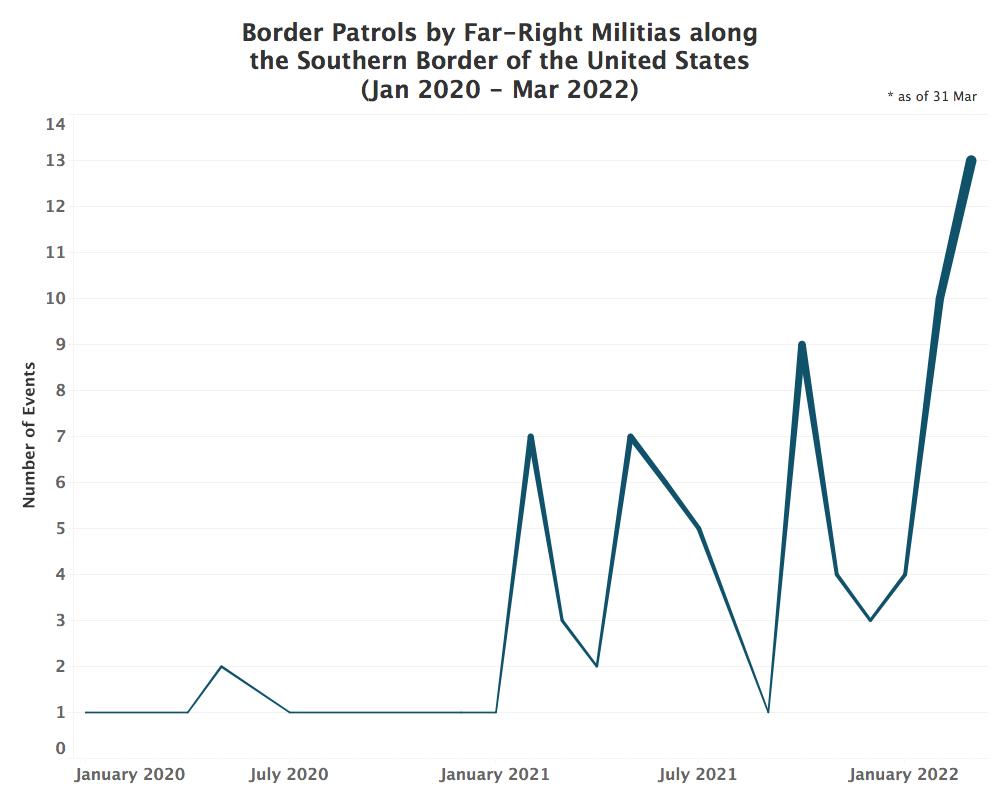

White nationalist and white supremacist activity is on the rise, accounting for the majority of demonstrations involving militias and MSMs in late 2021, and fueling offline propaganda and border vigilantism. Last year came to a close with a major increase in the rate of demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs in support of white supremacy and white nationalism, with white supremacist and white nationalist demonstrations serving as the most significant driver of militia and MSM activity since their united response to the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. White supremacist and white nationalist activity has continued into 2022 in the form of demonstrations as well as increasing offline propaganda efforts and vigilantism, including anti-immigration mobilization on the border with Mexico.

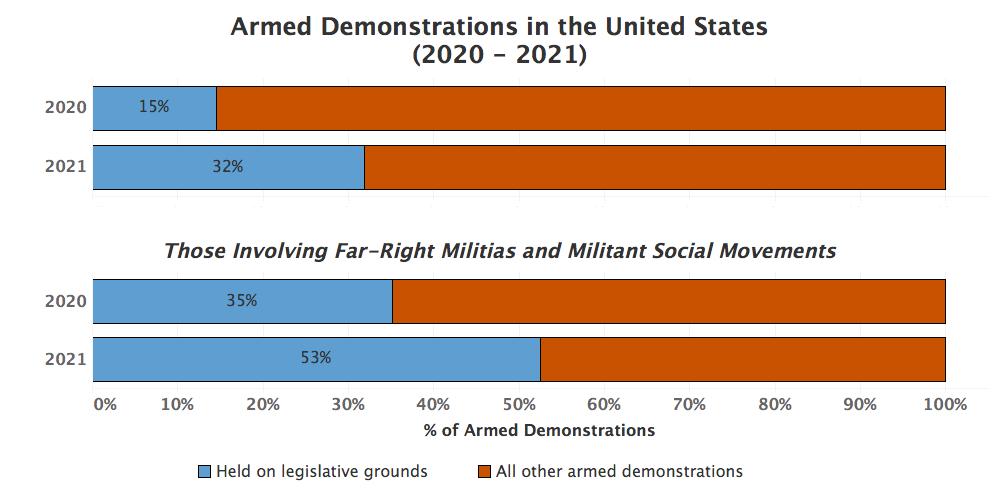

Demonstrations involving far-right groups are more frequently armed, and these armed demonstrations are increasingly focused on statehouses and legislative facilities. The rate of far-right militia and MSM engagement in armed demonstrations — which are six times more likely to turn violent or destructive than other demonstrations — is on the rise. Groups like the Three Percenters and the Boogaloo Boys are among the top actors involved in armed demonstrations, and particularly armed demonstrations at legislative facilities like state capitols. Armed demonstrations tended to take place at legislative facilities more often last year, including in states with contentious gubernatorial races like Michigan and Arizona: since 2020, the statehouses in Lansing and Phoenix have seen more armed demonstrations than any other state capitol buildings in the country.

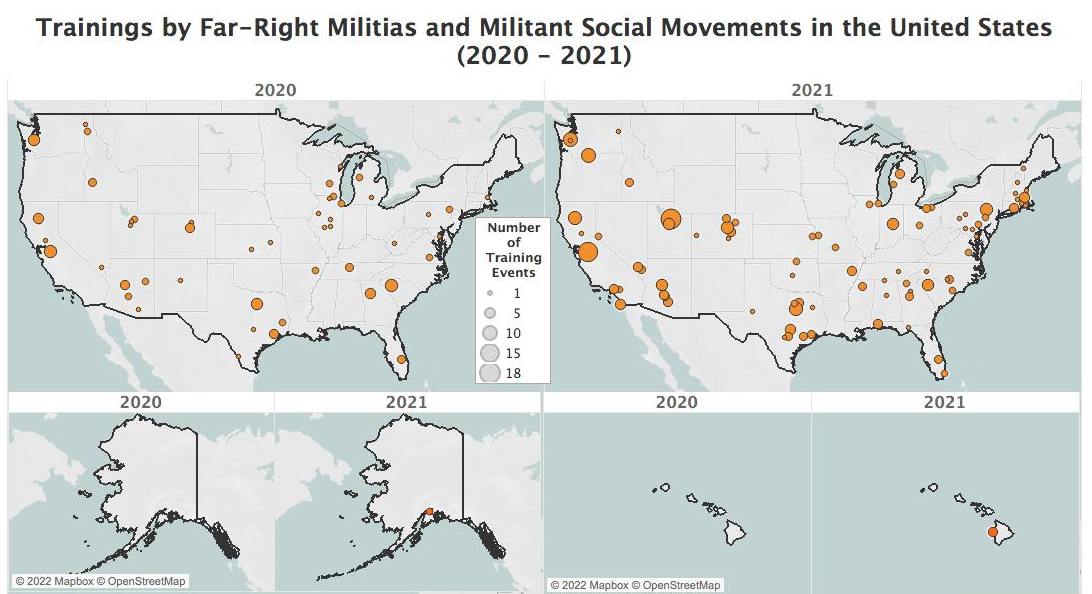

Beyond political violence and protest activity, far-right militias and MSMs are ramping up preparatory actions, such as recruitment drives and training exercises. Recruitment events increased significantly in 2021, particularly in states like Arizona where the Yavapai County Preparedness Team (YCPT), an Oath Keepers splinter group, has ramped up activity. At the same time, training exercises more than doubled nationwide driven by groups like American Contingency and Patriot Front, which expanded their training activities to twice as many states. These trends have continued into 2022.

Introduction

The total number of political violence events in the United States declined from 2020 to 2021. However, a narrow focus on aggregate trends in political violence can miss important new patterns and warning signs. For example, the total number of political violence events also declined by 2% globally from 2020 to 2021. Considered in isolation, this aggregate data point could suggest the world is becoming more peaceful, but it actually obscures multiple critical developments that together present a much different picture of the current conflict environment: political violence simultaneously became more lethal last year; it increasingly targeted civilians; and many national and regional declines in conflict were the result of tenuous ceasefire agreements. In the latter case, these fragile truces contributed significantly to the aggregate decline in conflict events, yet soon proved susceptible to major outbreaks of renewed violence, with the current crisis unfolding in Ukraine serving as only one of the most devastating examples. A deeper analysis of the data demonstrates that a simple decline in political violence events does not mean the underlying problems are resolved, and it may even distract from early warning signs that point to where these problems are only metastasizing. Across contexts, it is important to look at the nature of the violence, and especially the evolution of key patterns, to better understand shifting risks and threats — and the United States is no exception.

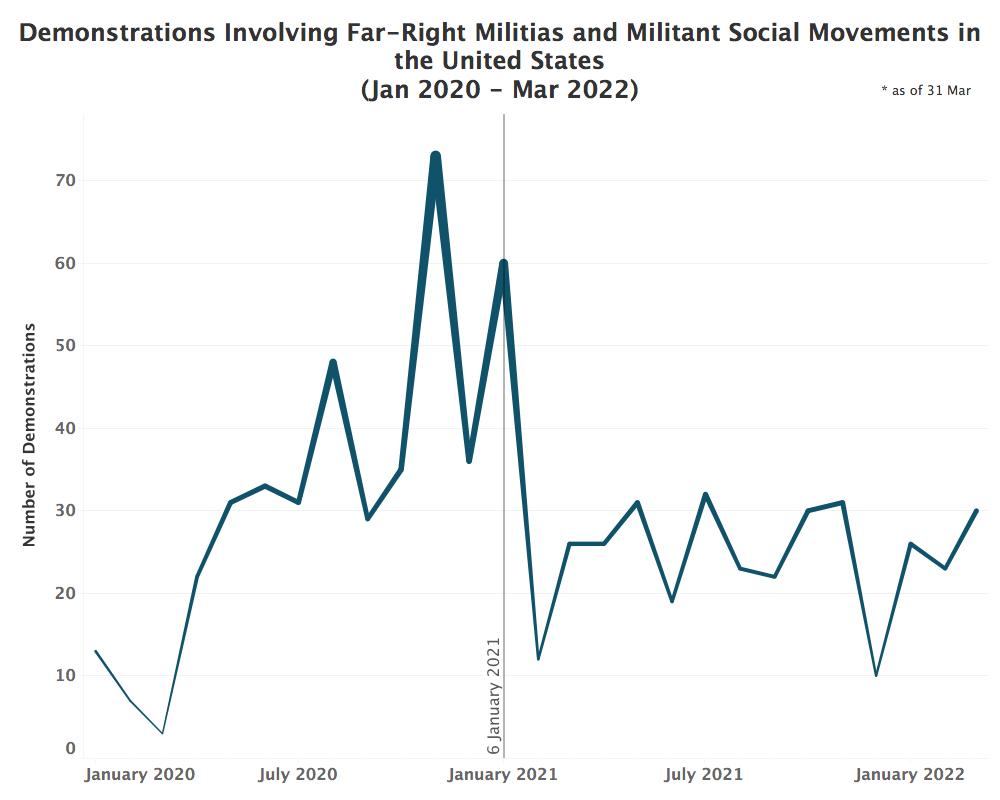

The overall decline in political violence in the United States is coupled with a significant decline in demonstrations from 2020 to 2021, by 41%. Demonstrations are the primary way in which political disorder manifests in the United States.1The United States is home to a robust protest environment. In 2021, it saw more demonstrations than anywhere else in the world, with the exception of India (a country with over four times the population). As such, a rise or fall in political violence alongside a rise or fall in demonstrations is to be expected. More specifically, however, the number of political violence events has declined since 6 January 2021, when right-wing rioters, led and organized by far-right militias and militant social movements (MSMs), stormed the United States Capitol building in an effort to overturn the results of what they say was a fraudulent presidential election. The decline in violence in the aftermath of the Capitol attack is likely in part a consequence of heightened legal and media focus on members and associates of far-right militias and MSMs, and especially those present at the riot.2For example: the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol (for more, see Atlantic Council, 2022).

Instead, over the past year, these groups have adapted their activity to fit the new environment. This has manifested through: a shift in demonstration engagement, with a focus on protests that allow for the co-option of new supporters “as part of a larger strategy to appear ‘more understated, friendly’”3This quote is from leaked internal chats of the leader of Patriot Front (a white supremacist hate group, and one of the far-right groups referenced here), as he described the group’s decision to engage in anti-abortion ‘March For Life’ events as a form of outreach to the largely conservative movement against abortion rights. (The Daily Beast, 28 January 2022); a heightened propensity for aggravating tensions at demonstrations by using violence and intimidation, bringing firearms, and countering other protesters; a rise in offline propaganda and vigilantism, especially motivated by white supremacy and white nationalism; and, an emphasis on preparatory mobilization, including recruitment drives and training exercises.

In recent years, political violence in the United States, and especially violence involving far-right militias and MSMs, has typically broken out in bursts around flashpoint events and issues, leading to intermittent spikes and declines — such as in response to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) demonstrations in the summer of 2020, or in the aftermath of the presidential election leading to the storming of the Capitol in January 2021 (see peaks and lulls in the graph below). Just as the low level of political violence in the immediate lead-up to the 2020 presidential election or in the immediate aftermath of the Capitol insurrection suggest, a lull in events does not mean that another burst of political violence is not around the corner.

The United States faces many latent risks, with groups and individuals often threatening more violence than they commit. Nevertheless, many American militias and MSMs are associated with a far-right ideology of extreme violence towards communities opposed to their rhetoric, as well as a desire for dominance and control. Earlier ACLED research has found that the lack of open condemnation of these groups from public figures and select local law enforcement has given them space to operate. When such groups are active in ‘friendly environments’ — where local authorities are allies or where state or national authorities are, at best, silent or, at worst, tacitly or openly supportive — they are further able to thrive. This has also allowed sympathetic political figures to claim little direct responsibility for violent actions from which they hope to benefit. It has been even easier for groups to cultivate these environments in cases where they can achieve some of their aims (e.g. preparatory objectives, like training and recruiting) without violence. This is especially true in cases where there has not yet been a proximate flashpoint event around which such groups may rally. In such contexts, even when there may be a lull or an overall decline in violent incidents, groups may be actively becoming more organized, more effective, and more deeply entrenched in local spaces. This means they could be more capable of committing serious violence in the future if they perceive a threat or are triggered when a flashpoint does occur. In short, past patterns of political violence involving far-right militias and MSMs, coupled with their adaptation to the post-6 January landscape, suggest that shifts in the activity and strategy of these groups can serve as precursors or early warning signs of political violence to come. To properly track these early warning signs, a more nuanced understanding of the risks associated with political violence in the United States is needed, taking into account the evolution of these trends.

Analysis of ACLED data indicates that there have been multiple shifts in demonstration activity involving these groups, and the right-wing more generally, including changes in the drivers of demonstrations in which far-right militias and MSMs engage. These shifts have contributed to, and in turn have been shaped by, the drivers of right-wing mobilization in the United States more largely. Never static, drivers continue to evolve over time as a result not only of group responses to the political environment, but also of strategic choices by groups aiming to gain momentum to increase engagement with right-wing communities and individuals that may have formerly been distinct from those in the militia milieu. Each of these shifts in strategy has allowed for networking and coalition building with new populations, providing new organizing opportunities for far-right militias and MSMs.

Within these demonstrations, there has been an increase in the use of violence by certain far-right groups, like the Proud Boys. Increased street violence at demonstrations, coupled with a decline in law enforcement engagement in demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs, raises the risks that groups like the Proud Boys will continue to escalate. This creates a high-risk environment for more aggressive — and potentially even lethal — violence at demonstrations, which may target counter-protesters as well as bystanders, including media. Such violence could continue to escalate beyond street protests to school boards, reproductive health clinics, polling sites, vote-counting centers, and other potential targets of far-right mobilization.

There has also been an increase in the rate of engagement of far-right militias and MSMs in armed demonstrations (i.e. events in which demonstrators carry firearms, regardless of whether they use and shoot such firearms). This has been especially the case for armed demonstrations at legislative grounds, which are often aimed at intimidating lawmakers. This is a worrying trend on two counts: both in the aftermath of United States Capitol attack, which was largely organized by far-right militias and MSMs;4New research suggests that such groups may have played an even more significant role on 6 January 2021, given the links that a considerable number of individuals present that day had to such groups (Twitter @MikeAJensen, 14 April 2022). and in the aftermath of the Kyle Rittenhouse case, in which Rittenhouse was acquitted of all charges for shooting three – and killing two – demonstrators in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in August 2020.

Furthermore, counter-demonstrations – where one group of protesters ‘counters’ another – have been increasingly turning violent or destructive, and the rate of violent or destructive activity is elevated in demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs. These demonstration trends, taken together, suggest that protests involving far-right militias and MSMs are becoming increasingly contentious — another concerning trend as demonstrations continue to be the primary way in which such groups engage in the political disorder landscape in the United States.

One increasingly salient mobilizer has been white supremacy and white nationalism.5While white supremacy and white nationalism are closely linked (i.e. “many ‘white nationalists’ are also ‘white supremacists’ because they believe white people are inherently superior to other races”), the two terms are distinct (Columbia Journalism Review, 14 August 2017). In the interest of space, however, they are used interchangeably here. White supremacy and white nationalism have been important drivers of far-right demonstrations, especially since the ‘Unite the Right’ rally held in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 (ADL, September 2018). In late 2021, white nationalism served not only as the primary driver for demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs, but also as the most significant driver of far-right militia and MSM activity since the united response of such groups to the BLM movement. Outside of demonstrations, there has been an increase in offline propaganda dissemination, as well as a rise in vigilantism and anti-immigrant activity along the border with Mexico.

Lastly, in addition to demonstration activity and engagement in propaganda and vigilantism, a number of far-right militias and MSMs have increased their preparatory mobilization through a rise in both recruitment drives and training exercises. An increase in such activity at the same time as a decline in demonstration activity on aggregate underlines the importance of tracking a wide variety of indicators to monitor latent risks.

The continued — and always evolving — activities of such groups, including those involved in the violence at the Capitol, underscore the risk of further political violence in the United States. This is especially so in the run-up to the midterm elections, which could serve as a national flashpoint as well as a local-level flashpoint in states and municipalities home to more contentious political races.

Using new ACLED data,6While this report reviews data for the first quarter of 2022, ACLED data are published in near-real time. For the latest data, see the ACLED website. this report explores these shifting trends and the potential for violence during the midterms. ACLED tracks these activities in real time via a wide and deep sourcing strategy that includes: thousands of traditional media sources, especially local newspapers; trusted social media accounts of journalists and smaller media outfits; information gathered by partner organizations; and, primary sources, such as Telegram channels and platforms used by militia groups or MSMs themselves,7While a number of such sources are cited throughout this report, links are purposefully not included in order to avoid the amplification of such voices and accounts. amongst others.8For more on ACLED’s data collection strategy, see the methodology resources at the US Research Hub.

Far-right Militias and Militant Social Movements

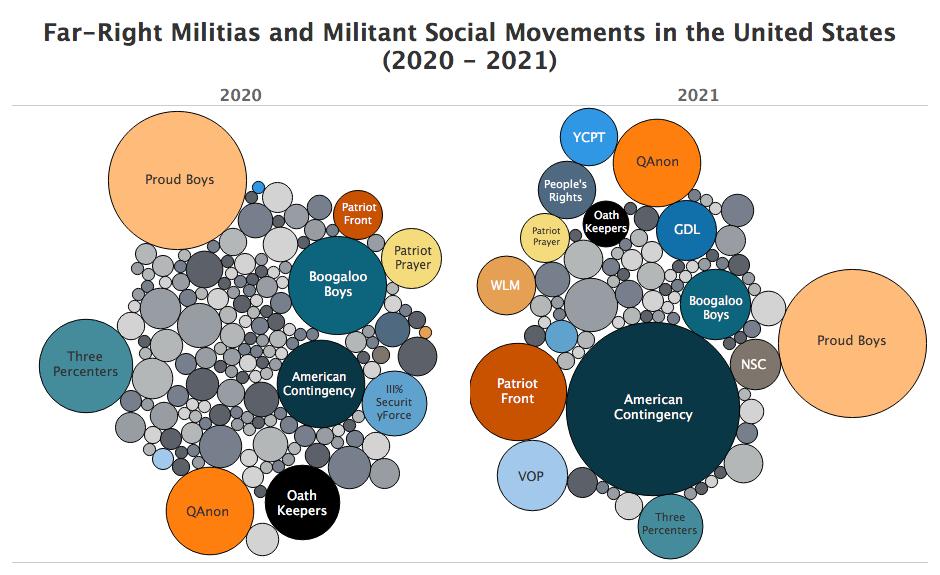

While more distinct, named, right-wing militias and MSMs were active in 2020 than in 2021 (from 157 in 2020 down to 80 in 2021), a number of these groups significantly increased their activity last year, resulting in a landscape of more defined and mobilized actors (see figure below). This trend matches reports finding that while “the overall number of hate groups declined in 2021, some groups experienced rapid growth, as well as increased influence and access to the political mainstream” (SPLC, 2022).

Far-Right Militias and MSMs with the Greatest Increase in Activity from 2020 to 2021

| Number of Events | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Actor | 2020 | 2021 | Change |

| American Contingency | 51 | 200 | 149 |

| Patriot Front | 16 | 63 | 47 |

| VOP: Veterans on Patrol | 3 | 33 | 30 |

| GDL: Goyim Defense League | 1 | 24 | 23 |

| WLM: White Lives Matter | 1 | 23 | 22 |

| Yavapai County Preparedness Team | 1 | 22 | 21 |

| Proud Boys | 127 | 146 | 19 |

| NSC: Nationalist Social Club | 2 | 17 | 15 |

The increased activity of each of the actors noted in the table above — in addition to the Boogaloo Boys and the Three Percenters, which were two of the most active groups in 2021 — contributes to the wider shifts seen in right-wing mobilization. First, there has been a shift in protest dynamics. The Proud Boys, for example, which is already one of the most violent groups in the country, have begun to rely even more on violent tactics at demonstrations. Additionally, far-right militias and MSMs have more often engaged in armed demonstrations, especially on legislative grounds. The Boogaloo Boys and the Three Percenters have been especially active in these demonstrations, contributing to the increase.

Another protest-related shift has been the rise of white nationalism as a driver. Groups like Patriot Front and the Nationalist Social Club (NSC), as well as more loosely organized protest movements such as White Lives Matter (WLM), have contributed to this trend. Even outside of demonstrations, there has been a rise in the dissemination of offline propaganda supporting such ideologies, with the GDL most significantly engaged in such actions. There has also been a rise in vigilantism, tied to white nationalism, as groups like VOP have attempted to take border control into their own hands, patrolling the border with Mexico, particularly in Arizona, and regularly detaining migrants, who they often claim to hand over to Border Patrol agents.

Preparatory mobilization has also been on the rise. Recruitment drives have significantly increased, with the Yavapai County Preparedness Team (YCPT) contributing significantly to this trend. YCPT activity has been limited to Arizona and has contributed to the rise in recruitment events being centered in that state. Training exercises for militias and MSMs also rose drastically. Exercises — such as pistol, marksmanship, and carbine trainings held by American Contingency or close-quarters combat and sparring trainings held by Patriot Front — have contributed significantly to that trend. These various developments are explored in further detail below.

Demonstrations

Right-wing Demonstration Drivers

The drivers of demonstration activity often evolve over time, and the American right-wing is no different. Since the start of 2020 when ACLED’s coverage of the United States began, a multitude of right-wing drivers have motivated involvement in demonstrations. These have ranged from: opposition to the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including opposition to the COVID-19 vaccine and vaccine mandates in particular;12Demonstrations against COVID-19 restrictions include demonstrations against any restrictions imposed by the government (ranging from local to federal level) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes: those arguing that restrictions contravene constitutional rights; those against specific restrictions, such as mandatory mask mandates, stay-at-home orders, online schooling, etc.; those calling for the complete reopening of the economy and the state; those calling for the reopening of specific sectors of the economy or specific local businesses, as well as those in support of businesses or individuals who defy restrictions. Some of these demonstrations have been known as ‘reopen protests’ or ‘anti-lockdown protests.’ A subset of these anti-restriction demonstrations includes those in opposition to COVID-19 vaccines, vaccination, and vaccine mandates, which are referred to as anti-vaccine demonstrations. While not all of these protests are necessarily ‘right-wing,’ the subset that includes the presence/involvement of far-right militias or MSMs can be considered as such. opposition to the BLM movement, and support for police and law enforcement;13Anti-BLM/pro-police demonstrations include demonstrations: in support of police, including but not limited to movements like ‘Blue Lives Matter’ and ‘Back the Blue;’ and those which specifically counter demonstrations in support of the BLM movement (including those against systemic racism and police brutality, including but not limited to those formally organized by the BLM movement); and instances in which members of far-right militias or MSMs, often armed, showed up at pro-BLM protests to ‘provide security’ for the community against ‘violence and rioting’ by pro-BLM demonstrators. support for former President Donald Trump, both during his presidency and afterward, including support for the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement in particular;14 Pro-Trump demonstrations include those in support of Donald Trump, both those during his presidency and since then. Anti-Biden demonstrations are not included here; while some such protests are indeed pro-Trump, not all are. A subset of these demonstrations is in support of unfounded allegations that the November 2020 presidential election was ‘stolen’ from Donald Trump as a result of widespread electoral fraud, rejecting the presidential victory for Joe Biden. These are referred to as ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations. support for the Second Amendment (2A);15Pro-2A demonstrations include demonstrations in support of the Second Amendment, as well as those advocating for gun rights more largely. Demonstrations involving groups created specifically around the promotion of such rights (e.g. Open Carry Texas) are also included here. support for white supremacy and white nationalism;16White supremacist or white nationalist demonstrations include demonstrations in which protesters specifically advocate white supremacist and/or white nationalist ideals (e.g. ‘White power!’), as well as those in which a white supremacist or white nationalist group, including neo-Nazi groups, takes part (e.g. Goyim Defense League, Nationalist Social Club, the Ku Klux Klan, etc.). opposition to abortions; to opposition to the teaching of Critical Race Theory (CRT), and more.

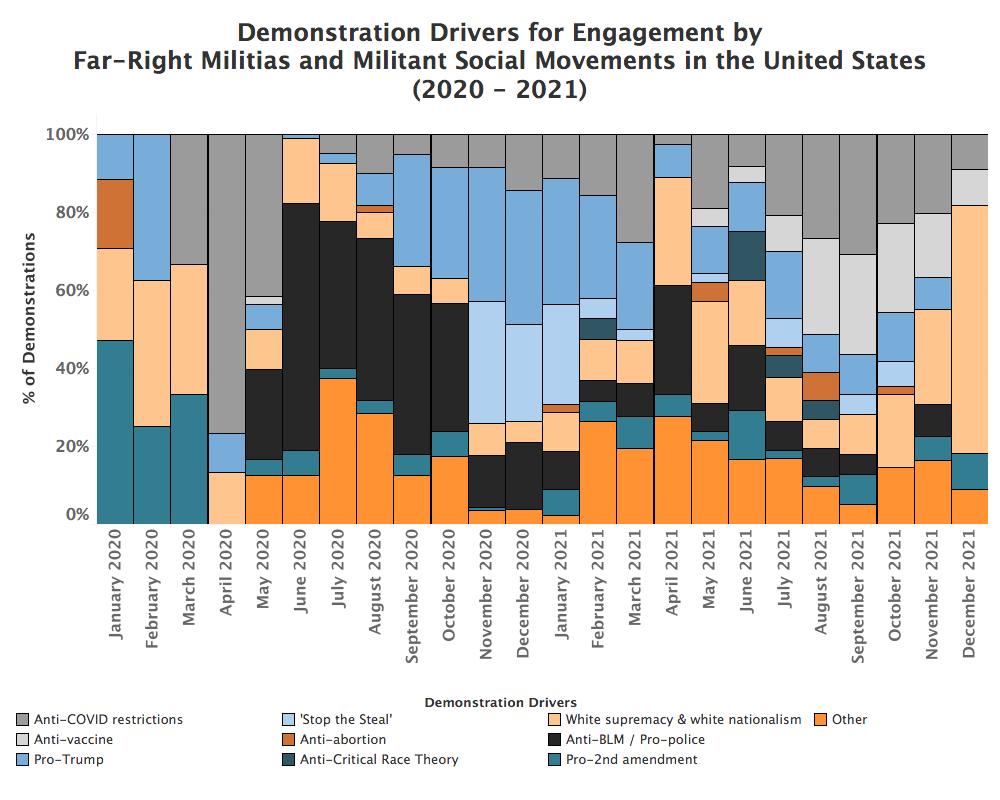

Certain drivers have attracted support specifically from far-right militia groups and MSMs, especially through the distinct networking and coalition building facilitated by mobilization around certain drivers. Looking at the subset of demonstrations involving militias and MSMs is important. When such groups are involved in right-wing demonstrations (defined here as demonstrations around the drivers noted above), the demonstrations are 12 times more likely to turn violent and/or destructive. Further, such groups have been engaging in right-wing demonstrations more often. The graph below visualizes the activity of these groups in right-wing demonstrations over 2020 and 2021 in order to better depict their involvement within the protest landscape.17All demonstrations involving right-wing militias and MSMs have been reviewed, with those that fit multiple drivers counted alongside each driver (i.e. double-counted). As the graph represents proportional distribution and not aggregate event counts, this helps to capture the saliency of all drivers explored here, avoiding cases in which some drivers may be obscured due to their co-occurring alongside other drivers. This is often the case, given the active cross-pollination that occurs within these protests.

Early 2020

At the start of 2020, the dominant drivers motivating the engagement of far-right militias and MSMs in demonstrations included white nationalism (in peach in graph above), opposition to abortion rights (in brown), pro-2A activism (in teal), and pro-Trump support (in blue). Support for white nationalism and white supremacy on the right has been renewed in recent years following the white supremacist ‘Unite the Right’ rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017. Demonstrations against abortion also traditionally spike in January, in conjunction with the annual ‘March for Life’ (for more, see this ACLED infographic). Pro-2A activism saw a national push at the start of 2020, especially following a call-to-action in Richmond, Virginia, organized by the Virginia Citizens Defense League (VCDL) on 20 January 2020.18MilitiaWatch notes how VCDL used that call-to-action to set up a number of militias in the following months. With 2020 marking an election year, this resulted in pro-Trump demonstrations being more common as well.

Many of these demonstrations served as networking opportunities by drawing on multiple motivators. For example, the ‘March for Life’ rally on 24 January 2020 in Washington, DC, brought together thousands of anti-abortion activists, along with the white nationalist Patriot Front,19These reports come from a Telegram channel run by Patriot Front, purposefully not linked to here. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch. as well as President Trump himself,20President Trump’s participation in the event made him the first sitting president to take part in the ‘March for Life’ (NBC, 4 January 2020). along with his supporters (USA Today, 24 January 2020). A number of satellite protests were held across the country around the same time. For example, one held in Austin, Texas, brought together anti-abortion supporters, some armed, with pro-2A supporters like Open Carry Texas.21These reports come from a Youtube channel reporting on militias, purposefully not linked to here. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch.

Spring 2020

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a pandemic in March 2020, with the Trump administration announcing a national emergency soon after. With COVID-19 cases on the rise, states began to impose restrictions to curb the spread of the virus. Many far-right groups, ostensibly organized in opposition to ‘big government,’ viewed these restrictions as an ‘overstep’ and began to mobilize and build networks against the regulations amongst a wide movement of groups. President Trump encouraged such mobilization in Minnesota and Michigan, and advocated for anti-restriction activism in Virginia specifically in connection to gun rights, tweeting: “LIBERATE VIRGINIA, and save your great 2nd Amendment. It is under siege!” (Detroit News, 17 April 2020). This mobilization served as an opportunity for cross-pollination, allowing far-right groups to build new connections and coalitions amongst groups on the right. For example, on 31 March 2020, a protest organized by the pro-2A VCDL took place against Virginia Governor Ralph Northam’s order to close indoor shooting ranges in response to the rise in COVID-19 cases (WBOC, 31 March 2020). The demonstration brought together those opposed to COVID-19 restrictions (in gray) with pro-2A supporters (in teal). A few weeks later, on 20 April 2020, over 100 protesters gathered in downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, against a stay-at-home order and to push for the reopening of non-essential business in the state. The demonstrators appeared alongside two Republican candidates for state congressional offices, as well as armed members of the Iron City Citizens Response Unit militia group wearing patches with the militia’s insignia, including a valknut (a symbol tied to white nationalism and white supremacy) (KDKA CBS2, 20 April 2020; TribLive, 20 April 2020; Pittsburgh City Paper, 24 April 2020). This brought together those opposed to COVID-19 restrictions with white nationalists (in peach) (for more on far-right mobilization in opposition to government pandemic-related restrictions, see this ACLED report).

Summer 2020

On 25 May 2020, George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was killed by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His death triggered a wave of social justice protests led by the BLM movement, which demanded justice for Floyd and rallied against racial inequality and police brutality in the United States more largely. While the majority of these demonstrations were peaceful, they were met not only by a heavy-handed law enforcement response, but also by opposition from far-right militias and MSMs (in black). In fact, at least 38 distinct, named, far-right groups have engaged directly with pro-BLM demonstrators. When such groups have engaged with pro-BLM demonstrators, the risk of violence has increased (for more on trends in BLM demonstrations and the response from law enforcement and far-right groups, see this ACLED report).

White nationalist and white supremacist groups were a fixture in such demonstrations (in peach). Counter-protesters wearing hoods, emblematic of the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan (KKK), were spotted at BLM demonstrations in early June in New York (The Daily Gazette, 6 June 2020) and Nevada (Fox11, 8 June 2020; Twitter @milesjbuergin, 8 June 2020), for example. That same month, the leader of the white nationalist Groypers participated in a counter-BLM protest in Queen Creek, Arizona (Daily Dot, 11 June 2020), while members of the neo-Nazi NSC attended a rally organized by the white nationalist Super Happy Fun America in Boston, Massachusetts, in opposition to the BLM movement (Boston Herald, 27 June 2020).

Pro-2A activism was also common in anti-BLM organizing (in teal), with armed groups showing up ‘to provide security against rioting’ becoming increasingly common at pro-BLM protests. On 6 June 2020, the Proud Boys held a protest, with some members armed, countering a BLM protest and also in support of the Second Amendment in Traverse City, Michigan (Associated Press, 13 June 2020). The following day, in Purcellville, Virginia, a local gun store owner held a ‘counter-protest BBQ’ in support of the Second Amendment and to counter a BLM protest, with some chanting “White Lives Matter” (Loudoun Times, 7 June 2020; Twitter @NoelPinson, 8 June 2020). Again, such cross-pollination allowed for organizing amongst otherwise distinct cross-sections of the right.

Fall 2020

In the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election in November, pro-Trump demonstrations (in blue) increasingly drew the support of far-right militias and MSMs, bringing together supporters across the right. For example, on 15 August 2020, more than 100 people — including pro-police ‘Back the Blue’ supporters, as well as supporters of the QAnon conspiracy theory — gathered outside of the DeKalb County Courthouse in Auburn, Indiana, to show support for President Trump’s re-election campaign (The Star, 15 August 2020). The following month, on 26 September 2020, in Yorba Linda, California, Trump supporters, including the white supremacist American Guard, counter-demonstrated against a pro-BLM rally (Twitter @ChadLoder, 3 May 2021). Protests like these served to bring together Trump supporters with anti-BLM and pro-police supporters, conspiracy theorists, and white supremacists, amongst others (for more on far-right militias and the 2020 presidential election, see this ACLED report).

In the immediate aftermath of the election, as it became clear that Joe Biden would likely win the presidency, ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations (in light blue) increasingly drew support from these far-right groups. For example, the ‘Million MAGA March’ on 14 November 2020 in Washington, DC, served to bring together thousands of ‘Stop the Steal’ supporters, including groups like the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers (BBC, 15 November 2020), and offered further networking opportunities amongst such groups. The Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers were ultimately instrumental in organizing and coordinating the storming of the United States Capitol in January 2021, marking the culmination of the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement (Washington Post, 15 March 2022) (for more on post-election right-wing mobilization and the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement, see this ACLED report).

Spring 2021

In the aftermath of the Capitol riot, demonstration engagement by many far-right militias and MSMs declined. With heightened legal scrutiny around members of these groups, especially those involved in storming the Capitol, many retreated and went to ground. As such, during the spring of 2021, a variety of other lower-level drivers (in orange) — such as rallying around Confederate monuments, promoting free speech, or opposing Democratic politicians — motivated the more limited activity of these groups.

Summer 2021

In the summer of 2021, a number of new motivators began to increasingly play a role in the mobilization of far-right militias and MSMs, in line with an adjusting of their audience. This strategy consisted of looking for supporters to co-opt rather than to express their own politics loudly and openly. The result was an increased engagement in demonstrations in opposition to both CRT (in navy) and abortion (in brown). These drivers allowed for networking with new populations, specifically those not traditionally part of the militia milieu, such as some parents and the religious right, respectively.

For example, on 23 June 2021, a member of the Proud Boys attended a protest at the Nashua Board of Education in New Hampshire to voice opposition to CRT (Twitter @miscellanyblue, 25 June 2021). A few weeks later, on 6 July 2021, the Proud Boys protested at a Granite School Board meeting in Salt Lake City, Utah, attacking CRT, despite the fact that CRT is already banned from school curricula in the state (The Salt Lake Tribune, 6 July 2021). Prior to the summer of 2021, the Proud Boys had only rarely engaged in any kind of protests around schools.

Similarly, the Proud Boys took part by ‘providing security’ for a Christian ‘prayer event’ on 7 August 2021 in Portland, Oregon, led by a ‘street preacher’ known for his opposition to abortion and homosexuality (Insider, 8 August 2021). Days later, on 10 August 2021, they demonstrated in Salem, Oregon, as part of a ‘prayer’ against abortion alongside other militia groups, many armed with bear mace, paintball guns, and firearms (Twitter @AlissaAzar, 21 August 2021). Prior to the summer of 2021, there were very limited cases of the Proud Boys appearing at demonstrations alongside Christian groups. These examples point to the strategic shift towards engagement in such demonstrations by groups like the Proud Boys (Vice News, 5 January 2022)22In addition to shifts in demonstration activity, such groups have also engaged in other strategies outside of such contexts, including: establishing legitimacy through engagement in mainstream conservative politics; decentralizing their organizations; and, focusing on local (rather than national) actions (Atlantic Council, 2022). (more on the impact of this new Proud Boys trend in the following section).

Late Summer and Fall 2021

Near the end of the summer, with the rise of the COVID-19 Delta variant and subsequent public health measures, mobilization in opposition to COVID-19 restrictions (in dark gray) increased. As the COVID-19 vaccine was shown to significantly reduce the spread and severity of the virus, vaccine mandates were implemented in certain contexts. With the imposition of these regulations, however, came a rise in demonstrations in opposition to COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine mandates (in light gray). For example, the ‘Summer of Love’ event held in Portland, Oregon, on 22 August 2021 — which ultimately devolved into violence — brought together various far-right demonstrators, including the Proud Boys, in opposition to COVID-19 vaccines and in support of freeing the supposed ‘political prisoners’ captured by law enforcement for their involvement in the Capitol riot (Youtube @News2Share, 22 August 2021; Oregon Public Broadcasting, 22 August 2021, 31 January 2022).

This trend of anti-restriction mobilization has since continued into 2022, most recently taking the form of ‘Freedom Convoys.’23American ‘Freedom Convoys’ were inspired by events in Canada. For more on trends in Canadian ‘Freedom Convoy’ demonstrations, see this ACLED fact sheet. For example, on 23 February 2022, hundreds of people and semi-truckers, including Three Percenter adherents and QAnon supporters amongst others, convoyed from Adelanto, California, to Kingman, Arizona, as part of a cross-country journey to Washington, DC — driving slowly to delay traffic and displaying signs and flags to demonstrate against COVID-19 vaccine mandates (Twitter @az_rww, 23 February 2022; Twitter @LCRWnews, 23 February 2022; Twitter @BGOnTheScene, 23 February 2022; Twitter @OneUnderScore_, 23 February 2022).

Late 2021

2021 came to a close with a significant increase in the rate of demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs in support of white nationalism and white supremacy (in peach). While activity around this driver has risen in recent years in the aftermath of the ‘Unite the Right’ rally in 2017, the recent spike in such organizing relative to other drivers is stark. White nationalism is the most significant driver of far-right militia and MSM activity since the united response of such groups to the BLM movement (see figure below). This includes protest activity by groups and movements like NSC, National Socialist Movement (NSM), GDL, Patriot Front, and WLM,24White Lives Matter is a protest series, rather than a formal group. amongst others. Support for white nationalism has continued into 2022, not only in the form of demonstrations, but also through the increased spread of offline propaganda and a rise in vigilantism (explored in further detail below).

What to Expect in 2022

While white nationalism has continued to drive far-right militia and MSM activity in 2022, these groups have also increasingly engaged in demonstrations against pandemic-related public health measures, and especially vaccines. ‘Freedom Convoys’ around the country have contributed significantly to this trend.25In early 2022, anti-COVID-19 restrictions and anti-vaccine mandates became increasingly salient drivers of far-right militia and MSM activity in protests, driven by ‘Freedom Convoys.’ However, as of late April 2022, white supremacy and white nationalism are again the primary driver of far-right militia and MSM protest activity in the US. However, with many mask and vaccine mandates being lifted as the latest wave of the COVID-19 Omicron variant subsides,26Even when COVID-19 cases rise, hospitalizations remain low given immunity rates in the population (New York Times, 29 April 2022), making government restrictions less of a necessity. a new shift is due in protest organizing and engagement by far-right militias and MSMs.

As an election year with midterms as well as a number of key gubernatorial races, 2022 is likely to see a rise in organizing focused on the upcoming votes. There have already been examples of protests involving ‘Freedom Convoys’ expressing support for Trump and including voter registration opportunities at events, signaling the start of this evolution (Washington Post, 19 March 2022).

In addition to election-related mobilization, there may also be a resurgence of other recent drivers as well. With Republican officials launching a new anti-LGBT+ legislative push around the country (The Atlantic, 10 March 2022), mobilization against LGBT+ rights may increase, even though coordinated organizing on this issue has not been a major feature of the political violence and protest landscape in which far-right militias and MSMs have engaged in recent years. Broader activity on the right is currently coalescing around the reinvigorated anti-LGBT+ legislative campaign, in addition to organizing against institutions and companies seen as ‘too supportive’ of LGBT+ rights. Similar to the cross-pollination opportunities that protests and activism in opposition to CRT and abortions offered, anti-LGBT+ mobilization could offer the same ripe environment for far-right militias and MSMs to make inroads with the wider right-wing activist community. In light of the significant backlash from the LGBT+ community and its supporters that has already taken place in response to new anti-LGBT+ legislation, this driver also has the likelihood to usher in a significant rise in counter-demonstrations. As anti-LGBT+ rhetoric from right-wing political and media figures intensifies, these encounters could become increasingly contentious, raising the risk of protest violence as well as separate attacks targeting members of the LGBT+ community by extremist individuals and far-right groups. Since the beginning of ACLED coverage in 2020, the LGBT+ community has been one of the most frequent targets of mob violence in the United States; notably, incidents of political violence targeting the LGBT+ community in the United States thus far this year have already exceeded the total number of attacks reported last year.27ACLED only tracks cases of serious physical violence that are reported to be solely politically rather than interpersonally motivated. This is a limited subset of all violence against the LGBT+ community at large, which is a much larger set of violence. For example, on 1 April 2022, a violent mob made up of masked men attacked organizers, performers, and attendees of a Latinx drag show at a Mexican eatery and bar in Pasadena, California, as they departed the venue. At least three of the victims were hospitalized as a result of the attack (LA Times, 31 March 2022).

Violent Demonstrations

Understanding the shifts in far-right militia and MSM involvement in different types of demonstrations can provide early warning signs of which protests might be at risk of experiencing violence given the propensity of certain groups to engage in violent action, especially in cases where their demonstration activity is on the rise.

For example, the Proud Boys were more active in 2021 relative to 2020, engaging in about 15% more events (see table above). This is in line with the dramatic rise in the number of active Proud Boys chapters across the country, despite the legal battles faced by many members of the group as a result of their role in the Capitol attack (SPLC, 2022). The overall rise in Proud Boys activity has in turn been accompanied by a rise in violence. The group engaged in 12 more violent demonstrations in 2021 compared to 2020 – a 57% increase. Approximately 25% of all demonstrations involving the Proud Boys turned violent in 2021 relative to 18% in 2020. For comparison, only about 6% of demonstrations involving pro-BLM groups turned violent or destructive in 2020, and that figure dropped to about 4% in 2021, underlining how disproportionately violent groups like the Proud Boys are relative to other types of movements.28This is especially pertinent relative to the BLM movement, which was framed as extremely violent in the media and public narratives.

This trend has continued into 2022. For example, on 20 February 2022, while a group of Proud Boys demonstrated on an overpass in Sacramento, California, with a banner drop that read “We’ll Have Our Home Again,” several Proud Boys attacked a member of a citizen journalist group who was filming the event (Twitter @BlackZebraPro, 21 February 2022a). Video of the attack was later uploaded showing several Proud Boys beating the man, one with a metal pole, while shouting homophobic slurs (Twitter @BlackZebraPro, 21 February 2022b).

Given their propensity for violence, tracking shifts in the activity of a group like the Proud Boys can be useful in identifying the types of protests that are at higher risk of turning violent. For example, as noted above, prior to the summer of 2021, there were very limited cases of the Proud Boys appearing at demonstrations alongside Christian groups or at abortion-related demonstrations. As the group has increasingly engaged in such demonstrations, there has been a concomitant rise in violence at abortion-related demonstrations. In fact, from 2020, there had been no reports of abortion-related demonstrations turning violent or destructive29While there have not been reports of abortion-related protests turning violent or destructive, there have been reports of other such activity targeting abortion providers. For example, on 3 January 2020, a man approached a Planned Parenthood clinic in Newark, Delaware, and spray-painted Deus Vult (‘God Wills It’ in Latin) onto the building before throwing a Molotov cocktail at the building, damaging a window and the porch. The man had posts on his social media that professed anti-abortion messages. He was later arrested by the FBI and charged with maliciously damaging a building with fire and intentionally damaging a facility that provides reproductive health services (New York Times, 7 January 2020) until summer 2021, and all abortion-related demonstrations that have turned violent or destructive since then have involved the Proud Boys.

The increase in violent activity by groups like the Proud Boys has been met with an overall decline in intervention by law enforcement. While authorities took a heavy-handed approach to demonstrations associated with the BLM movement in the summer of 2020, they responded more conservatively to demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs, including openly violent groups like the Proud Boys.30 This is in line with research that finds that left-wing protesters are more likely to be arrested than right-wing protesters (Wood, 2020). This is true even though demonstrations involving the latter are approximately twice as likely to turn violent or destructive as those involving the former (less than 6% of all pro-BLM demonstrations have turned violent or destructive, compared to over 11% of demonstrations involving far-right militias or MSMs).31In 2020, at the height of the BLM movement when response by law enforcement was most heavy-handed, pro-BLM demonstrations still only turned violent or destructive about 6% of the time, while demonstrations involving far-right militias or MSMs turned violent or destructive over 12% of the time — an even higher rate. The divergent response comes despite leaked law enforcement documents that suggested police knew that “far-right extremists were the real threat at protests” (The Intercept, 15 July 2020). Since then, the limited rate of law enforcement intervention in demonstrations where these groups are active has only further declined. In 2020, authorities engaged in 8% of all demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs, while in 2021 this figure dropped to less than 7%. So far in 2022, police have engaged in less than 5% of these demonstrations.32 In fact, in some cases, such as the ‘March for Life’ rally in Washington, DC, on 21 January 2022, police engagement in the protest appears to have been to escort Patriot Front members (Youtube @BGOnTheScene, 24 January 2022).

Armed Demonstrations and Rallies at Legislative Grounds

Some of the groups that reduced their activity from 2020 to 2021 — such as the Boogaloo Boys and the Three Percenters — still remained among the most active groups in the country last year. Both of these groups are also among the top actors involved in armed demonstrations, and particularly armed demonstrations at legislative facilities — a subset of armed demonstrations that became more common last year (see figure below). Armed demonstrations are correlated with higher risks of violence: these events turn violent or destructive six times more often than unarmed demonstrations. Both the Boogaloo Boys and the Three Percenters engaged in armed versus unarmed demonstrations more often in 2021 relative to 2020, which could signal a shift in strategy by the groups. Furthermore, these armed demonstrations tended to take place on legislative grounds more often in 2021 relative to 2020 (see figure below).

It is notable that these armed demonstration trends have not only persisted but also intensified during a non-election year, in the aftermath of the Capitol attack. That these trends have already continued into 2022 underscores the risk of further escalation in armed demonstration activity going into the upcoming midterm elections this year.

Armed demonstrations can impact free speech and lawful protests by providing a ‘chilling effect,’ intimidating other protesters as well as officials, particularly when these demonstrations take place on legislative grounds. The proportion of armed demonstrations at statehouses and other legislative facilities has increased as proponents of the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement have mobilized to assert greater control over state election systems around the country. In the lead-up to midterm elections this year, which includes contentious gubernatorial races in states like Michigan and Arizona, this trend threatens to further aggravate tensions and raise the risk of violence. Notably, the capitol buildings in Lansing, Michigan, and Phoenix, Arizona, have been home to more armed demonstrations than any other state capitols since the start of ACLED coverage.

Counter-demonstrations

Counter-demonstrations have also increasingly turned violent or destructive since 2020. Counter-demonstrations, in which two groups of demonstrators ‘counter’ one another, make up a subset of demonstrations that are at particularly high risk of violence, as they are contentious and often involve direct confrontations between opposing sides. Overall, counter-demonstrations turn violent and/or destructive five times as often as other demonstrations, at 10% of the time relative to 2% of the time, respectively. This rate has increased over the years. In 2020, over 9% of counter-demonstrations turned violent and/or destructive, or nearly three times as often as other un-countered demonstrations, which turned violent and/or destructive only 3% of the time. In 2021, not only did this rate of violence at counter-demonstrations increase to over 11%, the difference between counter-demonstrations and other un-countered demonstrations also widened. Counter-demonstrations in 2021 turned violent and/or destructive over 11 times as often as other un-countered demonstrations, which turned violent/destructive only 1% of the time.

This rate, and increase, is even higher in demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs (see figure below). In 2020, one-fifth of counter-demonstrations involving far-right militias and MSMs turned violent and/or destructive. In 2021, the rate increased to one-third of all counter-demonstrations involving these groups.

As tensions mount in the lead-up to the midterm elections, it is likely that these trends will continue. So far in 2022,33This report examines trends through the first quarter of 2022 (1 January through 31 March 2022). two counter-demonstrations have turned violent, both of which have involved white supremacists. The first, on 29 January 2022, involved members of the NSM gathering in Orlando, Florida, in support of Nazism, which was met with counter-demonstrators. NSM demonstrators waved flags with swastikas, performed Nazi salutes, chanted “White power!,” “Heil Hitler!,” and anti-Semitic slogans and slurs, and also signaled opposition to President Biden by carrying signs with the phrase “Let’s Go Brandon!” (a popularized anti-Biden chant) (NBC News, 31 January 2022; Spectrum News13, 31 January 2022; Tequesta Black Star, 30 January 2022). Reports note that NSM demonstrators “assaulted bystanders and accosted people recording [the incident]” (Tequesta Black Star, 30 January 2022). At the demonstration, physical violence took place when a man was punched by NSM members; two NSM members, including the local leader of the group, were later arrested and charged with battery (Sun Sentinel, 4 February 2022; CBS12, 4 February 2022). On 11 March 2022, pro-Trump student counter-demonstrators threw rocks and other projectiles at a group of students protesting at Western High School in Davie, Florida,34“Davie is a semi-rural town on the western edge of Broward County known for its horse and cattle pastures and rodeo grounds” (Sun Sentinel, 11 March 2022). Western High School is one of the most white schools in the county (It’s Going Down, 15 March 2022). rallying against ‘Don’t Say Gay’ state legislation, which aims to restrict school discussions of sexual orientation and gender, while chanting “White power!” (Sun Sentinel, 11 March 2022; It’s Going Down, 15 March 2022). After counter-demonstrators threw projectiles, the groups began to clash, resulting in several students sustaining minor injuries. One student, after being cornered by the pro-Trump demonstrators on a second floor balcony, broke his leg after jumping from the balcony to escape (It’s Going Down, 15 March 2022).

White Supremacy and White Nationalism

White supremacy and white nationalism have become increasingly common drivers of protest dynamics, as noted above, and they have also increasingly motivated activity outside of demonstrations, both in the form of offline propaganda and border vigilantism (explored in further detail below).

Dissemination of Offline Propaganda

The internet has long provided fertile ground for propaganda linked to white supremacy (Wired, 31 January 2021). Platforms like social media (PBS, 24 August 2021; USA Today, 8 December 2021) and video gaming (Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 January 2022) allow groups to organize, network, and mobilize (Pacific Standard, 15 August 2017). On such platforms, neo-Nazis have increasingly relied on meme culture, with the targets of their hate often including Black people, LGBT+ groups, Jews, the American government, and, particularly, women (GNET, December 2021).

Amid the proliferation of online propaganda, however, white supremacists and white nationalists have increased activities to spread propaganda offline, such as banner drops and the distribution of flyers.35This is in line with findings from the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) that “antisemitic incidents reached an all-time high in the United States in 2021” (ADL, 2022). Not only do such efforts aim to radicalize people, but these offline activities also contribute to a feedback loop as they are in turn reported on by online platforms, widening the overall reach. This rise in offline activity has occurred against a backdrop of social media companies and online platforms taking further action against extremist content, as well as investigations by researchers and journalists and digital targeting by ‘hackers.’ The result has been a “great scattering” of such individuals from social media platforms and many alternative online platforms more largely (Atlantic Council, 2022), which may be a contributing factor in the renewed surge in offline propaganda efforts. These trends could shift in light of recent events — including the purchase of Twitter by Elon Musk with plans to ‘return free speech’ to the platform, which has resulted in celebrations on the far-right (Insider, 26 April 2022; New York Times, 26 April 2022). The move may attract back some of those who had left or had been kicked off the platform (Washington Post, 25 April 2022).

Anti-Semitic propaganda distributed by the neo-Nazi conspiracy network GDL blaming Jewish people for the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as promoting the GDL more largely, spiked in late 2021 and early 2022 (NBC News, 25 January 2022). Racist flyers promoting local KKK chapters and ‘White Lives Matter’ also saw an increase in distribution last year (Patch, 17 June 2021). In addition to flyers, there have been numerous banner drops displaying slogans like ‘White Lives Matter’ (Twitter @VPS_Reports, 16 January 2022), some coordinated by NSC chapters (Twitter @EoinHiggins_, 12 February 2022).

Border Vigilantism

Beyond propaganda and intimidation efforts via flyers and banners, far-right white nationalist militias have also increasingly engaged in vigilantism along the border with Mexico, especially in Arizona, taking it upon themselves to ‘patrol’ and target migrants (SPLC, 2 December 2021; Sounds Like Hate, 2021). Groups including VOP, the Arizona Border Recon Militia, the AZ Patriots, and the Arizona Desert Guardians have been leading participants in this movement, which recently intensified and reached a zenith this year (see figure below).36This report examines trends through the first quarter of 2022 (1 January through 31 March 2022).

As of the end of March 2022, VOP had already conducted over 60 patrols in Arizona along the border with Mexico. February and March were the busiest months for militia border patrols since the start of ACLED coverage in 2020.37These reports come from a Telegram channel reporting on border events associated with VOP, purposefully not linked to here. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch. During these patrols, they often encounter migrants, including children, which they claim to hand over to US Border Patrol. During one of these encounters in February, VOP was joined by Ron Watkins, a Republican candidate for Congress and prominent QAnon figure.38This report comes from a Telegram channel reporting on border events associated with VOP, purposefully not linked to here. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch. VOP activity increased 11-fold from 2020 to 2021, from three patrols to 33, making them the most active group in Arizona last year. In the first quarter of 2022, the group already conducted 26 patrols. If this rate continues, the group will have increased its patrols by over 200% in 2022 relative to 2021.

The increase in VOP activity in 2021 was the most significant contributor to the rise in far-right militia and MSM activity in Arizona. As a result, Arizona registered the greatest increase in far-right militia and MSM activity of any state between 2020 and 2021, with activity more than doubling (other trends, including a significant increase in recruitment drives and training exercises, also contribute to this trend, and are explored in more detail below).

Beyond VOP, other groups have also taken part in border vigilantism. Around 11 January 2022, armed members of Patriots for America conducted a patrol in an area along the border near Del Rio, Texas, during which they encountered migrants and reportedly handed them over to the sheriff’s department.39This report comes from a page reporting on border events, purposefully not linked to here. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch. That such groups seem to have arrangements with law enforcement — allegedly turning over individuals that they ‘arrest’ to local authorities and the federal Border Patrol although such activity is illegal — raises additional concerns (Brookings, 12 March 2021). This is especially so given that friendliness and close relationships between government authorities and militia groups can be a further driver of militia activity.

Increased Preparatory Mobilization

In addition to the threats associated with the increased propensity for groups to use violence at demonstrations, the proliferation of firearms at protests, the intensification of counter-demonstration trends, and the surge in offline propaganda and vigilantism, other factors contributing to latent risks have also been on the rise, such as far-right militia and MSM recruitment drives and training exercises.

Engagement in demonstrations by far-right militias and MSMs declined in 2021 alongside the overall decline in demonstrations more largely after the spike in protest activity for and against the BLM movement in summer 2020. Political violence involving far-right militias and MSMs surged that summer, as it did again in January 2021, both in Washington, DC and elsewhere in the country. As discussed above, engagement in demonstrations by many far-right militias and MSMs decreased further in the aftermath of the Capitol riot, and it has remained at a relatively reduced rate since (see figure below). It is likely that heightened legal and media attention has contributed to depressing activity by far-right militias and MSMs at such events, which can draw cameras and documentation. A push instead towards preparatory action (explored in this section) — ahead of the next flashpoint or trigger for wider mobilization — may be a product of such strategic shifts.

Recruitment Drives

Recruitment drives increased from 2020 to 2021, even though the total number of distinct far-right militias and MSMs involved in recruitment events declined by half. While some previously active groups continued to hold recruitment events, such as the Oath Keepers, the increase is driven primarily by new groups, such as the YCPT, which officially splintered from the Oath Keepers in April 2021.40This splintering followed (and is likely tied directly to) the national platform the Arizona chapter of the Oath Keepers (then the largest chapter of the Oath Keepers) received via 60 Minutes on 18 April 2021, in which they criticized the national head of the Oath Keepers (CBS News, 18 April 2021). Beginning in June 2021, the YCPT began to hold recruitment events twice a month, every month.41As of this writing, only one YCPT recruitment event has been reported during March 2022. However, this may increase as reporting on such events emerges with some lag at times. The YCPT has held at least eight recruitment and public information meetings in Arizona since the start of 2022,42 This report examines trends through the first quarter of 2022 (1 January through 31 March 2022). with the majority held in Chino Valley.43This information comes from YCPT’s own webpage, purposefully not linked to here. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch. In addition to recruitment drives, the YCPT has also provided a number of Republican candidates and elected officials with campaign stops during their meetings, allowing for a built-in audience for politicians seeking to curry favor with the militia movement and its supporters (MilitiaWatch, 28 June 2021).

The emergence of new actors like the YCPT can indicate a change in the political violence environment. In high-activity spaces, like Arizona, which was home to a higher than average rate of political violence in 2020,44 Per ACLED data, Arizona was in the top tertile of states in 2020 when it came to political violence. new actors can often form as a result of the factionalization of existing groups. This has been the case with YCPT, which splintered from the Oath Keepers over concerns that the national body was unresponsive and not useful (MilitiaWatch, 28 June 2021). In such contexts, the frequency and intensity of actions may increase, especially those involving a new group. Further, lessons from research into conflict zones around the world indicate that civilians may often bear the burden of activity by new and emergent actors, especially as such actors are typically weaker than those already present or those they may have splintered from. In order to demonstrate their role and make a name for themselves, these groups may target civilians they see as opponents (for more, see the Emerging Actor Tracker at ACLED’s Early Warning Research Hub). The YCPT’s regular reference to ‘civil war’ (internally and externally) raises concerns about future violence (MilitiaWatch, 28 June 2021).

Training Exercises

In addition to recruitment drives, training exercises by far-right militias and MSMs have also increased considerably — by over two and a half times — despite the fact that only about a third as many far-right militias or MSMs held exercises in 2021 relative to the year prior. Both American Contingency and Patriot Front significantly increased the number of training exercises they held in 2021 by over four times, and expanded these trainings to twice as many states (see maps below). These two groups already topped the list for training exercises in 2020, underscoring how much further they ramped up their training programs in 2021.

American Contingency was formed with the explicit agenda to counter protests across the country in 2020, decrying a failure of the ‘traditional’ United States, with the group’s network often used for sharing ‘intelligence’ on left-wing demonstrations planned in particular regions.45For more, see this joint report by ACLED and MilitiaWatch. The significant rise in American Contingency training events amid the increased role of militias and MSMs in right-wing demonstrations and counter-demonstrations (described above) is a worrying combination. Patriot Front, meanwhile, is a white nationalist hate group, splintering from Vanguard America in the aftermath of the ‘Unite the Right’ rally in 2017 (SPLC, 2022).46The founder of Patriot Front led Vanguard America members in the ‘Unite the Right’ rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, which resulted in the death of an activist (SPLC, 2022). The rise in Patriot Front trainings within the context of increased mobilization by white supremacist and white nationalist groups in protests, offline propaganda, and border vigilantism, points to the potential for more widespread — and more effective — mobilization by such hate groups in the future.

These trends have continued so far this year. For example, Patriot Front has already held at least eight training events in 2022,47This report examines trends through the first quarter of 2022 (1 January through 31 March 2022). At least four more trainings have already been reported since the end of March 2022. primarily sparring trainings in eastern Massachusetts.48These reports come from a Telegram channel run by Patriot Front, purposefully not linked to here. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch. Other white supremacist movements have also held training exercises this year, including the first reported training exercises — a fitness and sparring training — by WLM and the Rise Above Movement in an undisclosed location in southern California on 10 January.49This report comes from a telegram channel reporting Active Club activity in the US and other neo-Nazi actions. This source is shared by ACLED’s partner, MilitiaWatch.

Looking Forward

Political violence in the United States, and specifically political violence involving far-right militias and MSMs, typically manifests in peaks and lulls. In this context, the recent decline in aggregate events should not be taken as a sign that the threat of political violence has abated. On the contrary, current trends indicate that it may only represent a relative calm before the next storm.

The United States faces many latent risks, and a wide range of factors that can contribute to and elevate these risks are intensifying. Such factors include the ascendance of extremist protest drivers like white supremacy, the spread of armed demonstrations at legislative facilities and statehouses, and increases in training and recruitment actions. Monitoring these factors and these groups will be critical for detecting new and emerging threats, particularly in the lead-up to potential flashpoint events around this year’s midterm elections.

As part of the regular evolution of protest drivers shaping the demonstration dynamics of far-right militias and MSMs, another shift in the near future is likely, especially because current drivers such as opposition to pandemic-related restrictions may soon wane as COVID-19 cases decline. In the coming months, mobilization is expected to pick up around the elections. It is also expected to increase in response to the resurgence of recent drivers, like white nationalism, as well as newer drivers, such as support for anti-LGBT+ legislation (The Atlantic, 10 March 2022). While the LGBT+ community has long been a target of right-wing groups (The New Yorker, 19 September 2019), coordinated mobilization against LGBT+ rights, especially involving militias and MSMs, has not been a major feature of the political violence and protest landscape in recent years. This may soon change.

The evolution of mobilization drivers involving far-right militias and MSMs may also result in the emergence of different risks. The recent shifts towards the even greater use of violence by groups like the Proud Boys, and the increased propensity for counter-demonstrations to turn violent, especially when involving far-right militias or MSMs, is in line with a broader embrace of violence on the right (SPLC, 2022). The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), for example, finds that in the post-6 January world, “nearly one in five Americans (18%) agree with the statement ‘Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country’” (PRRI, 2021). Republicans are more likely to agree with the statement than independents or Democrats, especially those who trust far-right news sources and those who support former President Trump (PRRI, 2021). As elections draw near, amplifying increasingly salient political divisions, these trends must be monitored with a view toward preventing and mitigating the risk of violence.

Update, 15 June 2022: This report has been updated to clarify that the LGBT+ community is one of the most frequent targets of mob violence in the United States, and that incidents of political violence targeting the LGBT+ community thus far this year have already exceeded the total number of attacks reported last year. Please note that ACLED only tracks cases of serious physical violence that are reported to be solely politically rather than interpersonally motivated. This is a limited subset of all violence against the LGBT+ community at large, which is a much larger set of violence. For more on anti-LGBT+ mobilization in the United States, see this fact sheet.