10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Afghanistan

Mid-Year Update

High Risk of Violence Targeting Civilians Under Taliban Rule

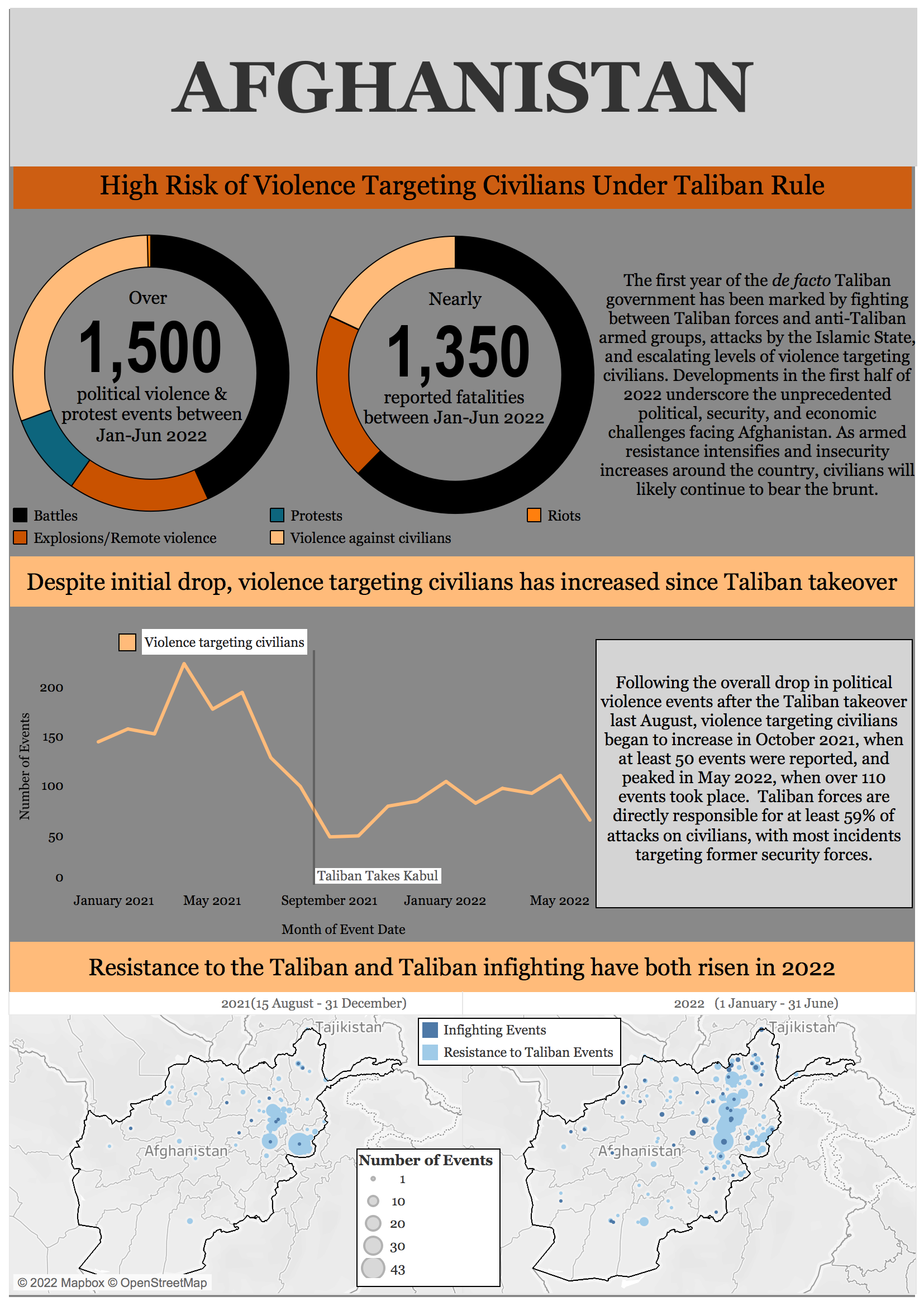

One year on since the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan has seen continued insecurity marked by fighting between the Taliban and anti-Taliban armed groups, attacks by the Islamic State (IS), and worsening civilian targeting. At the beginning of the year, ACLED assessed that civilians were at heightened risk for violence under Taliban rule, and this risk has grown during the first half of 2022 amid an uptick in attacks by Taliban forces, IS, and unidentified perpetrators. Moreover, the de facto Taliban government has continued to restrict personal freedoms, especially women’s rights (Human Rights Watch, 18 January 2022), while also increasing repression of media and civil society. Within this context, alternate sources of information such as Afghan Peace Watch (APW) — a local conflict observatory and ACLED partner — have played a critical role in maintaining coverage of disorder patterns in Afghanistan (for more, see ACLED and APW’s joint report on Tracking Disorder During Taliban Rule in Afghanistan).

The National Resistance Front (NRF) has ramped up attacks on Taliban forces in 2022, with over 300 NRF-Taliban battles recorded by ACLED in the first six months of the year. The majority of clashes took place in the northeastern Baghlan and Panjshir provinces. NRF activity has also been recorded in western Herat and central Daykundi provinces for the first time this year. Fighting between the NRF and the Taliban has particularly risen in recent months, with activity peaking in May and remaining at heightened levels in June. The NRF reported seizing territory from the Taliban in Takhar and Panjshir provinces, while the Taliban has mobilized thousands of troops to northern Afghanistan to contain the NRF (Hasht e Subh, 8 June 2022). Since December 2021, the NRF has additionally increased rocket and shelling attacks targeting Taliban bases, while Taliban forces have attacked the NRF with air and drone strikes in Panjshir and Takhar.

At least nine other armed anti-Taliban1As per ACLED methodology, actors are coded as anti-Taliban groups when explicitly reported to be formed to fight the Taliban. They engage in violence and/or declare their support for larger, organized armed groups, such as the National Resistance Front. For more, see ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around Political Violence and Demonstrations in Afghanistan. resistance groups have emerged in 2022, engaging in over 100 armed clashes with Taliban forces during the first half of the year. The most active of these groups has been the Afghanistan Freedom Front (AFF), which has engaged in at least 59 clashes with the Taliban since its formation in March 2022 (Twitter @AfgFreedomAFF, 11 March 2022). The National Liberation Front of Afghanistan and the Afghanistan Liberation Movement have both been involved in over a dozen armed clashes or remote explosive events. Notably, they have attacked Taliban forces in southern provinces like Kandahar, expanding the geographic scope of resistance against the Taliban. ACLED also records attacks by other new armed groups like theWatandost Front, which claims to have seized territory from the Taliban in Ghazni province in May (Hasht e Subh, 9 May 2022), and the National Liberation Front of Afghanistan, which has engaged in over a dozen clashes with the Taliban. There had been little indication of military cooperation between resistance groups until two joint operations conducted by the AFF and the NRF in May and June. Some other groups also claim that they have maintained contact with the NRF (BBC, 24 May 2022).

IS has also continued attacks on Taliban forces in 2022. A recent upswing in IS activity reversed a decrease in early 2022 that came as Taliban forces conducted operations against IS militants, claiming to capture key IS members (France24, 22 April 2022). In June, ACLED records the largest number of armed interactions between IS and the Taliban since November 2021.

Meanwhile, Taliban infighting has increased in 2022, with nearly 60 incidents recorded during the first half of the year. This is a monthly average of roughly 10 Taliban infighting events, a rate nearly quadruple that of the period between the Taliban takeover last August and the end of 2021. The significant increase in infighting indicates that internal cohesion for the group continues to be a challenge. While motivations for the majority of events are difficult to verify, clashes along ethnic fault lines have been a visible pattern, with Pashtun Taliban members reportedly fighting with Uzbek or Tajik members. Ethnic tensions also reportedly played a role in the dismissal of a Hazara Taliban commander, who went on to lead a new militia that clashed with the Taliban in Sar-e Pol province in late June.

In line with ACLED’s expectations at the beginning of the year, civilians continue to bear the brunt of ongoing violence in 2022. Following the overall drop in political violence after the Taliban takeover in August 2021, which ended clashes between the Taliban and former Afghan military forces, violence targeting civilians began to increase steadily in October 2021, when at least 50 events were reported, and peaked in May 2022, when more than 110 events were reported. Taliban forces are directly responsible for approximately 59% of attacks targeting civilians reported during the first half of 2022. Former security forces are so far the most targeted group. Taliban forces have also detained, beaten, and killed civilians in the course of enforcing regulations based on the Taliban’s interpretation of Islamic law, such as bans on music during social gatherings and shaving beards for men (Reuters, 31 August 2021; RFE/RL, 6 October 2021). Additionally, in Baghlan and Panjshir provinces, newly mobilized Taliban forces have forcibly evicted residents and used their houses as military bases. Civilians accused of having links to the NRF have been detained, tortured, or killed (BBC, 16 May 2022).

Women are especially affected by new Taliban restrictions. Within the past year, government decrees have banned women from traveling without male company, have mandated full-body coverings in public, and have closed secondary schools for girls (VOA, 12 April 2022; The Guardian, 7 May 2022). These rules triggered over 50 women-led protest events during the first six months of the year. ACLED also records approximately 30 incidents where women were directly targeted by the Taliban during this period, as well as another dozen attributed to unidentified groups. These events include unknown perpetrators beheading women, the arrest and disappearance of civil society activists, and at least two cases of alleged rape by Taliban officials.

Perpetrators of violence targeting civilians are often unidentified: a third of all incidents in 2022 were committed by unknown actors. Targets of these attacks included journalists, civil society activists, and former security personnel. Half of these events were explosive attacks. Six of these targeted Muslim worshippers, killing over 100 people. On 29 April, unknown perpetrators carried out the deadliest attack of the year so far, targeting Sunni Sufis in Kabul city in an explosion that killed at least 50 people. The attack came ahead of the Muslim holiday Eid Al Fitr, during which IS targeted Shiite Muslims with explosives in Kabul and Kunduz provinces. IS has also engaged in extensive violence targeting civilians, launching more than 20 attacks during the first half of 2022. Approximately 50% targeted Hazara and Shiite Muslim groups, killing over 60 people.

Insecurity has also increased along the country’s periphery, marked by clashes and airstrikes on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border and occasional escalations in violence on the Iran-Afghanistan border. Over 40 cross-border incidents were reported during the first six months of the year, including cases where neighboring state forces engaged in clashes with the Taliban, perpetrated direct attacks against Afghan civilians, or fired artillery or launched airstrikes into Afghan territory. The number of incidents in 2022 already exceeds the number recorded in any full year since 2018.

Developments in the first half of 2022 underscore the unprecedented political, security, and economic challenges facing Afghanistan. The country’s economic crisis has deepened with reports of famine and climate change affecting agricultural production, exposing civilians to further risk (UN, 9 May 2022; Bloomberg, 6 April 2022). Despite the Taliban’s hold on government and military power, armed and civil resistance persists (Foreign Policy, 11 April 2022), with some observers highlighting how Afghan society has evolved prior to the fall of Kabul (Afghanistan Analysts Network, 15 June 2022), and how this could potentially raise the likelihood of further opposition to the new Taliban regime. Escalating levels of violence against civilians indicate that the Taliban is unlikely to ease its repressive policies and undertake substantive reform in the short term. As armed resistance intensifies and insecurity increases around the country, civilians will likely continue to bear the brunt.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s protests and riots event types.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and twenty-five types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riot event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type as well as specific explosions/remote violence events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.