10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Yemen

Mid-Year Update

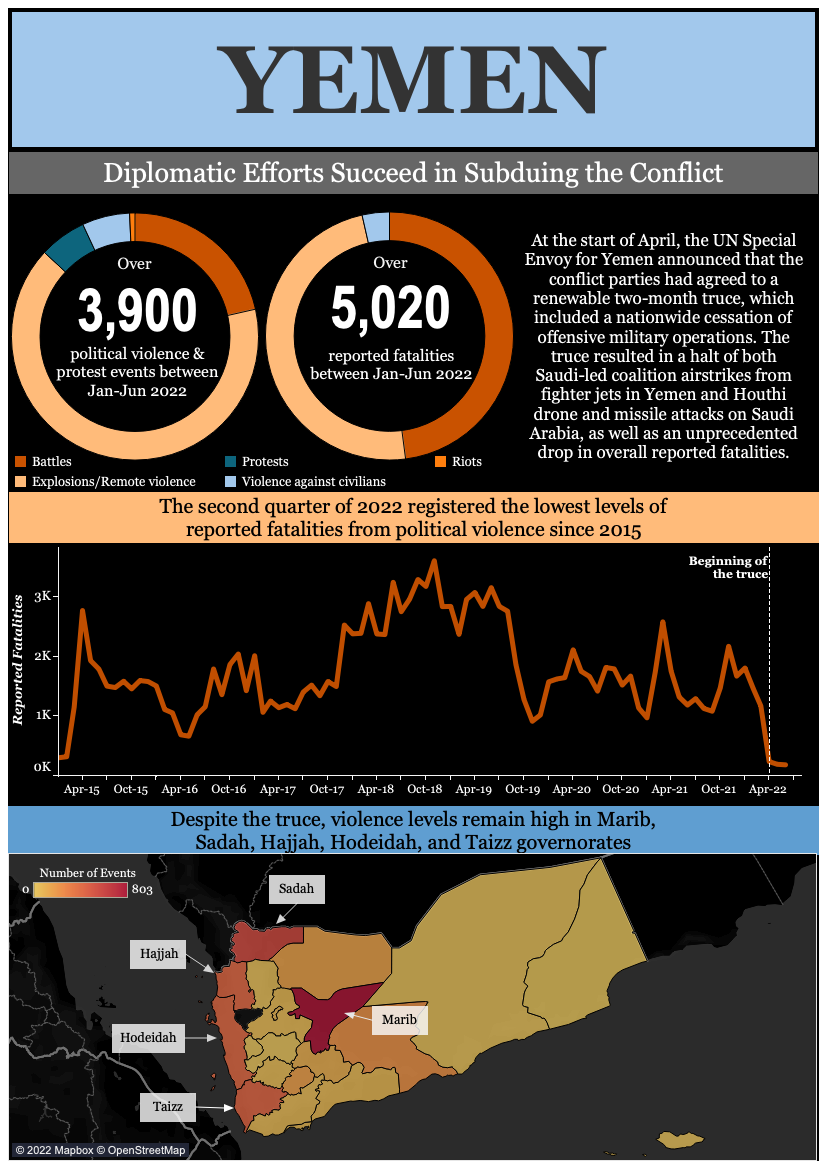

Diplomatic Efforts Succeed in Subduing the Conflict

At the beginning of the year, ACLED assessed that the faltering diplomatic process during the second half of 2021 and persisting military engagement provided bleak prospects for the first half of 2022. While heightened conflict activity in January supported this assessment, diplomatic efforts by UN Special Envoy for Yemen Hans Grundberg in March secured an unprecedented two-month truce between Houthi-affiliated authorities and the Internationally Recognized Government (IRG). The truce came into effect on 2 April. Registering a number of successes on the ground, the truce was initially extended for a two-month period until 2 August, and then for another two months until 2 October (Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, 2 August 2022).

In the first week of 2022, the UAE-backed Giants Brigades launched Operation ‘Southern Cyclone’ to oust Houthi forces from Shabwah governorate. Rapid gains made by Giants forces in Shabwah and their subsequent push into the southern districts of Marib governorate led to the highest levels of political violence in Yemen since March 2021. In response, the Houthis launched a drone and missile attack that resulted in the first fatalities caused by Houthi forces on UAE soil on 17 January. Following other aerial attacks, the Giants Brigades stopped their advances and announced the conclusion of the operation at the end of January.

Although political violence subsequently subsided in February, conflict worsened in Hajjah governorate as IRG forces, supported by Saudi-led coalition airstrikes and Saudi ground troops, launched an offensive against Houthi forces. The latter were quick to reverse IRG gains, but violence levels remained high in Hajjah throughout March as clashes continued. The first three months of 2022 were also marked by increases in Houthi drone and missile attacks on Saudi Arabia, as well as Saudi-led coalition airstrikes that targeted Houthi sites and caused civilian casualties in the capital city, Sanaa, in addition to Sanaa governorate more largely.

Despite these worrying trends, the diplomatic track regained momentum in March. UN Special Envoy Grundberg worked to secure a truce for the holy month of Ramadan, while Saudi Arabia also organized intra-Yemeni consultations in Riyadh. At the end of the month, both the Houthis and Saudi Arabia announced a unilateral cessation of hostilities. On 1 April, Grundberg announced a two-month renewable truce between IRG and Houthi forces to take effect the next day. The truce included a nationwide cessation of offensive military operations, the entry of fuel vessels into Hodeidah port, reopening Sanaa airport to commercial flights, and discussions on improving road access to Taizz and other governorates (Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, 1 April 2022).

This was the first time that the conflict parties had agreed to a nationwide cessation of hostilities since November 2016, as the result of what some argued was “a broad military equilibrium for the first time in several years” (International Crisis Group, 8 April 2022). The truce has been largely considered a success (Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, 25 May 2022). Over April and May, there was a halt to both Saudi-led coalition airstrikes from fighter jets in Yemen and Houthi drone and missile attacks on Saudi Arabia, a significant decrease in the lethality of armed clashes, and an unprecedented drop in overall reported fatalities (see this ACLED report for more on the impacts of the first two months of the truce, as well as ACLED’s Yemen Truce Monitor for weekly updates on truce violations). In August, the truce was again extended until 2 October, with the successes of its first two months so far persisting.

Despite these positive developments, however, civilians suffered disproportionately from continued violence during the initial two months of the truce. Although April and May saw the lowest levels of total reported fatalities since January 2015, the share of fatalities from civilian targeting increased by more than 50% compared to the two months prior. This trend has continued through the truce extension: in the third week of June 2022, fatalities from civilian targeting accounted for more than 50% of all reported fatalities for the first time since September 2015.

The initial truce period was also accompanied by shifts at the political level. Key among these was the unexpected replacement of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi as head of the IRG. On 7 April, amid the intra-Yemeni consultations in Riyadh, Hadi dismissed Vice President Ali Mohsen Al Ahmar and delegated his own executive powers to a newly established Presidential Leadership Council (PLC). Headed by former Interior Minister Rashad Al Alimi, the PLC includes seven other members from anti-Houthi factions with the most sway on the ground (Sana’a Center, 3 May 2022). Despite this move, some reports suggest that Saudi Arabia and the UAE imposed the PLC on Yemenis, with little prior planning or substantive input from its future members (Sana’a Center, 3 May 2022). Although one of the aims underpinning the PLC’s formation was to create a united, anti-Houthi front, some of its members have different and sometimes irreconcilable political agendas. This was illustrated when PLC member and President of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) Aydarus Al Zubaydi refrained from reading the word “unity” when taking the constitutional oath in April, underscoring the STC’s secessionist ambitions (South24, 19 April 2022).

On the ground, both positive and concerning developments have taken place with regards to the cohesion of the PLC. On 30 May, a joint committee was established, tasked with restructuring and unifying all security and military forces within the territories held by the PLC factions (Al Masdar, 30 May 2022). While PLC members will try to unite around their anti-Houthi position and prevent political fissures from developing into armed confrontations, skirmishes between anti-Houthi factions have already taken place in several areas since the creation of the PLC.

At the beginning of the year, ACLED warned that the stability of the southern governorates would need to be monitored. Although no major outbreak of violence has taken place so far, a wave of demonstrations against poor service provision and fuel prices erupted in Ad Dali, Aden, Hadramawt, and Lahij governorates in June. Wider civil unrest, with the risk of escalation into armed conflict, remains a possibility. Among further destabilizing factors, ACLED also records an increase in activity by Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in southern Yemen, as well as an apparent campaign by unidentified gunmen targeting southern security and military leaders.

Finally, ACLED noted that regional dynamics, particularly ‘secret’ talks aimed at restoring diplomatic ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, could have implications for Yemen in 2022. In line with Saudi Arabia’s main expectations from the talks (Middle East Eye, 13 May 2021), Houthi drone and missile attacks on Saudi territory have ceased, while direct talks on border security arrangements between senior Houthi and Saudi officials started in May (Reuters, 14 June 2022). It is unclear whether the Iran-Saudi Arabia talks played a role in these developments, although some observers suggest they did (The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, 18 May 2022). Going into the second half of the year, a reported move from ‘secret’ talks at the security level to public talks at the political level (Anadolu Agency, 22 July 2022) could have significant influence on the course of events in Yemen.

- The UN-Mediated Truce in Yemen: Impacts of the First Two Months

- Yemen Truce Monitor

- The State of Yemen: Mapping Territorial Control

- Little-Known Military Brigades and Armed Groups in Yemen: A Series

- The Myth of Stability: Fighting and Repression in Houthi-Controlled Territories

- The Wartime Transformation of AQAP in Yemen

- Yemen’s Fractured South: ACLED’s Three-Part Series

- Inside Ibb: A Hotbed of Infighting in Houthi-Controlled Yemen

- Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019

- ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Yemen Civil War

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s protests and riots event types.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and twenty-five types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riot event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type as well as specific explosions/remote violence events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.