10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Nigeria

Mid-Year Update

Multiple Security Threats Persist Around the Country

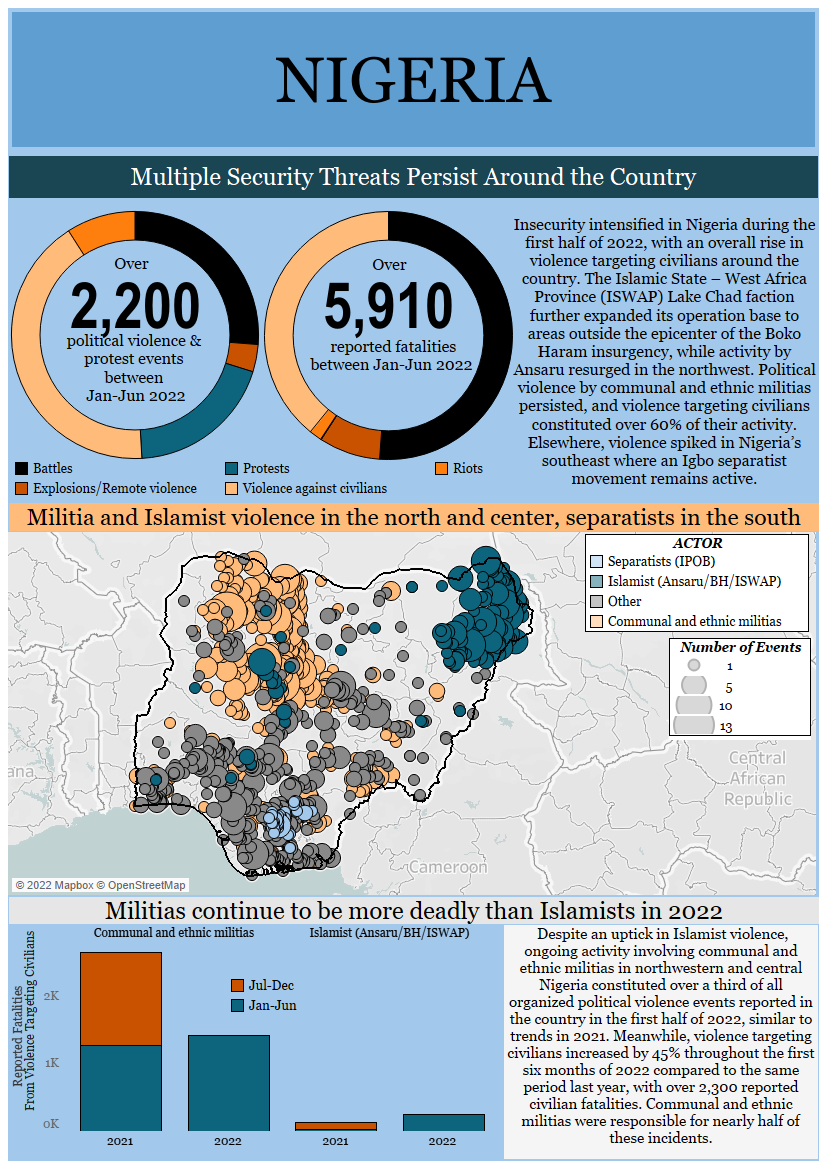

Insecurity intensified in Nigeria during the first half of 2022, with an overall rise in violence targeting civilians around the country. The Islamic State – West Africa Province (ISWAP) Lake Chad faction further expanded its operational base to areas outside the epicenter of the Boko Haram insurgency, while activity by Ansaru resurged in the northwest. Political violence by communal and ethnic militias persisted, and violence targeting civilians constituted over 60% of their activity. Elsewhere, violence spiked in Nigeria’s southeast where an Igbo separatist movement remains active.

While infighting between Boko Haram and ISWAP militants has continued, ISWAP also expanded its territorial zone of operations. The majority of events involving Islamist militants have occurred in Borno state, where the group has traditionally been active. However, in line with ACLED’s assessment at the beginning of the year, ISWAP moved further southward during the first half of 2022, increasing its activities in areas closer to the Federal Capital Territory. In Niger state, where ISWAP was reported to have set up camps last year (VOA, 3 October 2021), organized political violence events involving the group more than doubled during this period compared to all of 2021. ISWAP also claimed several attacks in Taraba, including an attack on a Catholic church in Mutum Biyu in January (The Sun Nigeria, 24 January 2022), as well as two separate bombings in April that targeted local bars in Iware and the Nukkai area of Jalingo (HumAngle, 23 April 2022). One month later, the group also took credit for another attack on Nigerian military forces in Jalingo. These are the first reported incidents perpetrated by Islamist militants in Taraba state since 2017. ISWAP has also been linked to attacks in states where it had previously not been present, with the group claiming several events in Kogi state from March to June. Further, the federal government blamed ISWAP for a deadly attack on a Catholic church in Owo, Ondo state, on 5 June, which resulted in at least 40 fatalities (Al Jazeera, 9 June 2022), though the group has not claimed responsibility.

Meanwhile, activity by Ansaru, a breakaway Boko Haram faction, resurged in the first half of 2022. After the group reiterated its allegiance to Al Qaeda at the beginning of the year (Long War Journal, 2 January 2022), Ansaru increased its operations, mainly clashing with communal militias in Kaduna and Zamfara states. Ansaru was largely inactive last year, with only one armed clash recorded by ACLED in Kaduna. Activity by the group had decreased after Nigerian military forces conducted operations against the group in 2020, including airstrikes.

Ongoing activity involving communal and ethnic militias in northwestern and central Nigeria constituted over a third of all organized political violence events reported in the country in the first half of 2022, similar to trends in 2021. Communal militias also overtook new territories during this period. In April, militiamen from Katsina and Zamfara states reportedly gained control of several communities in Gassol and Karim Lamidu Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Taraba state, establishing an operational base in Kambari town (Sahara Reporters, 10 April 2022). Government measures to curb violence by these militia groups — often called ‘bandits’ — have so far largely failed. In September 2021, the Nigerian government launched renewed campaigns in the country’s northwest, including airstrikes, movement restrictions, and the cutting off of communication networks (The Defense Post, 21 September 2021). The militiamen, however, have been able to evade the aerial bombardments (The Conversation, 22 April 2022). In January 2022, the government designated these groups as “terrorists” under the Terrorism Prevention Act (Al Jazeera, 6 January 2022). In Zamfara state, the local government has started the process for issuing licenses to qualified citizens to “obtain guns to defend themselves against bandits” (Al Jazeera, 29 June 2022).

Despite these measures, communal and ethnic militia activity has driven an increase in violence targeting civilians in 2022. Overall civilian targeting increased by 45% throughout the first six months of 2022 compared to the same period last year, with more than 2,300 reported civilian fatalities. Communal and ethnic militias were responsible for nearly half of these incidents. These militia groups frequently engage in kidnapping for ransom as an important source of income, with several mass kidnappings already recorded in 2022. For example, in March, a Kaduna militia group blew up the track on the Abuja-Kaduna route and opened fire on a train, killing eight people and kidnapping at least 65. As of July, dozens of hostages abducted in the attack remain captive (The Punch, 11 July 2022). Another militia group attacked civilians in Kanam LGA in Plateau state in April, killing over 100 people and abducting dozens. After a significant drop during the holy month of Ramadan, abductions are back on the rise, with June registering the highest number of abduction events ever recorded by ACLED. Although the Nigerian senate passed a bill barring ransom payments for hostage releases, aiming to cut off this source of income for kidnappers, the measure has been widely criticized for its potential to become a punishment for victims if signed into law (ABC News, 28 April 2022).

Further, a spate of violence hit southeast Nigeria during the first six months of 2022 as well, with an 80% increase in incidents compared to the same period last year. Unidentified armed groups are responsible for over half of these events. This surge has come in the context of a growing separatist movement in the region led by the Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB), as well as the government’s militarized response. The attacks have often been blamed on IPOB and its security outfit, the Eastern Security Network (ESN) (Premium Times, 3 April 2022). IPOB, however, has denied involvement in what it describes as “senseless and incessant attacks” in the southeast, calling on people “to rise and unite against bandits and Fulani herdsmen” (The Punch, 15 April 2022). It has, nevertheless, continued the intermittent imposition of sit-at-home orders in protest against the continued incarceration of its leader, Nnamdi Kanu, who is currently on trial in Abuja (The Guardian, 28 June 2022).

As federal and state elections draw closer – scheduled for February and March 2023, respectively – election-related political disorder has already started to increase, particularly in the southern states. During the presidential primaries held in May by the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) and a prominent opposition party, the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) (Al Jazeera, 27 May 2022), multiple deadly political violence events were reported. Election-related violence is expected to intensify further before the elections.

Facing growing insecurity across the country, Nigerian military forces are overstretched and poorly armed. Despite large-scale operations by the army and the regional Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against the Boko Haram insurgency, Islamist militants have been able to expand their areas of operation. The government campaign against ‘banditry’ has also proven largely unsuccessful, as civilians are increasingly facing attacks and abductions for ransom. Additionally, Nigerian military forces have been accused of perpetrating extra-judicial killings and war crimes (BBC, 12 December 2020; The Cable, 11 December 2020), with over 400 civilians killed at the hands of security forces since 2018 according to ACLED data. These issues will likely become the focus of electoral campaigns leading up to the 2023 elections.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s protests and riots event types.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and twenty-five types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riot event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type as well as specific explosions/remote violence events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.