10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Myanmar

Mid-Year Update

Continued Resistance Against the Military Coup

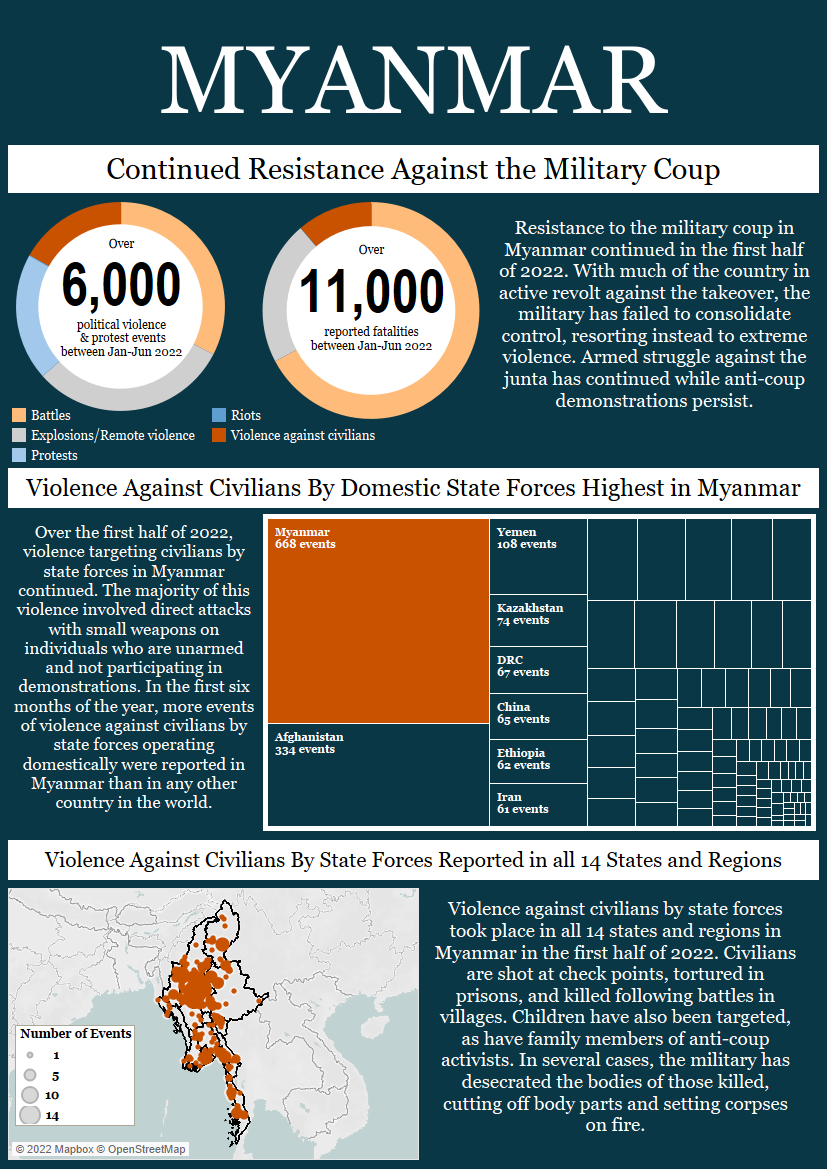

Resistance to the military coup in Myanmar continued through the first half of 2022. With much of the country in active revolt against the takeover, the military has failed to consolidate control, resorting instead to extreme violence. Armed struggle against the junta has escalated relative to the latter half of 2021, while anti-coup demonstrations persist.

Over the first six months of the year, state forces continued to engage in violence targeting civilians across Myanmar. The majority of this violence involved direct attacks with small weapons on individuals who are unarmed and not participating in demonstrations. During this period, more incidents of violence against civilians1This represents events coded by ACLED as event type violence against civilians. Myanmar also tops the list for violence targeting civilians as defined by ACLED, which is inclusive of events involving explosives/remote violence. Neither category includes violence impacting civilians in the crossfire of battles or violence impacting civilians as ‘collateral damage’ in an attack on a military target. (See this guide for more on ACLED’s definitions of political violence and protest.) The violence against civilians event type is chosen here as a more conservative measure in order to exclude remote violence events in which civilians may or may not have not been the designated target despite having suffered the consequences of the violence. by state forces operating domestically were reported in Myanmar than in any other country in the world. Civilians are frequently shot at check points, tortured in prisons, and killed following battles in villages. Children have also been targeted (United Nations, 13 June 2022), as have family members of anti-coup activists (Irrawaddy, 8 April 2022). In several cases, the military has desecrated the bodies of those killed, cutting off body parts and setting corpses on fire. In June, a video of a woman being beheaded was reported (Khit Thit Media, 28 June 2022), following an additional video of soldiers admitting to acts of severe violence, including beheadings (Radio Free Asia, 17 June 2022).

Pro-junta Pyu Saw Htee militias, composed of military veterans and nationalists, have also carried out violence against civilians (Irrawaddy, 29 June 2022; Frontier Myanmar, 14 July 2021). Other pro-junta militias have emerged as well, such as the Thway Thauk Aphwe (Blood Comrades Group),2This group’s name literally means “blood drinkers,” but figuratively implies the drinking of blood as part of an oath (Frontier Myanmar, 2 June 2022). The name has been translated into English as blood drinkers, blood comrades, blood brothers, and blood-sworn across different media sources. which earlier in the year began ‘Operation Red,’ a campaign of violence targeting the National League for Democracy (NLD). Victims of the group’s attacks have often been found with the group’s lanyard around their necks (Frontier Myanmar, 2 June 2022). Members of the media have also been threatened by the group for their reporting (Radio Free Asia, 2 May 2022).

Meanwhile, fighting between the military and armed resistance groups that emerged after the coup has intensified in 2022. There are indications that groups are organizing beyond the village level, with smaller groups joining together to operate at the township and district level. Alliances continue to be formed between local groups as well, with many battles involving more than one resistance group. While the relationships between the many armed resistance groups and the People’s Defense Force (PDF) under the National Unity Government (NUG), formed by elected lawmakers ousted in the coup, vary (Wilson Center, May 2022), forces under the NUG and those operating autonomously share the same goal of bringing down the military dictatorship.

Established ethnic resistance groups, including the Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) and the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA), have continued to support resistance groups that have emerged after the coup (Al Jazeera, 6 May 2022). In Kayin state, where battles spiked in March of this year, the combined forces of the KNU/KNLA, the Karen National Defence Organization (KNDO), and the PDF have engaged in intense fighting with the military. Meanwhile, the emergence in July of the Kawthoolei Army, headed by the dismissed former leader of the KNDO, has been met with opposition by the KNU (Mizzima, 25 July 2022). It is not yet clear how the many armed groups in the state will position themselves relative to this new group.

Elsewhere, in Rakhine state, tensions between the military and the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) have been increasing, as the ULA/AA has consolidated its control over parts of the state. A series of retaliatory arrests and abductions were reported throughout June and July, while the military held naval drills off the coast of Rakhine state in early July (Radio Free Asia, 6 July 2022). Although an informal ceasefire in place since shortly after the November 2020 election has largely been upheld, clashes have still been reported this year. On 4 July, a ULA/AA base in Kayin state was bombed by the military, resulting in the deaths of six ULA/AA members (Irrawaddy, 5 July 2022). The ULA/AA retaliated by carrying out attacks on the military in Maungdaw township in Rakhine state (Development Media Group, 27 July 2022). It remains to be seen whether further escalation in the conflict between the two groups will ensue.

Unarmed resistance to the military dictatorship has also persisted in 2022. Despite great personal risk to participants, demonstrations against the coup have continued, though at a lower level than last year. Still, in some locations, demonstrators have gathered daily to show their objection to the coup (Frontier Myanmar, 3 June 2022). In cities like Yangon, demonstrators continue to gather and quickly disperse to avoid being targeted. The military has cracked down on demonstrations by tracking and arresting activists before and after demonstrations. Mass arrests have also been carried out across cities with the intention of preventing demonstrations (Irrawaddy, 15 June 2022).

The military continues to discuss plans for an election, which they have indicated they plan to hold in 2023 (Myanmar Now, 1 August 2022). As noted by ACLED at the beginning of the year, the military is carrying out a campaign of violence against NLD members and supporters with the goal of eliminating any opposition at the ballot box. NLD members and supporters continue to be tortured and killed (Irrawaddy, 7 July 2022; Radio Free Asia, 18 July 2022). At the end of July, the military junta executed four political dissidents, including both U Phyo Zeya Thaw, a former NLD MP, and U Kyaw Min Yu (better known as Ko Jimmy), a well-known pro-democracy activist. The military has also moved NLD leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi from the undisclosed location where she has been held since the coup to a prison in Nay Pyi Taw, while she continues to be tried on politically motivated charges.

Political violence and protest trends seen in Myanmar at the start of the year are likely to carry on into the second half of the year. As the military incurs further losses and fails to gain control of significant parts of the country, it will continue to target civilians with extreme acts of violence. Resistance to the coup – both armed and unarmed – shows no signs of stopping.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s protests and riots event types.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and twenty-five types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riot event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type as well as specific explosions/remote violence events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.