10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Sudan

Mid-Year Update

Military Factions Enhance Their Power Amid Spreading Violence

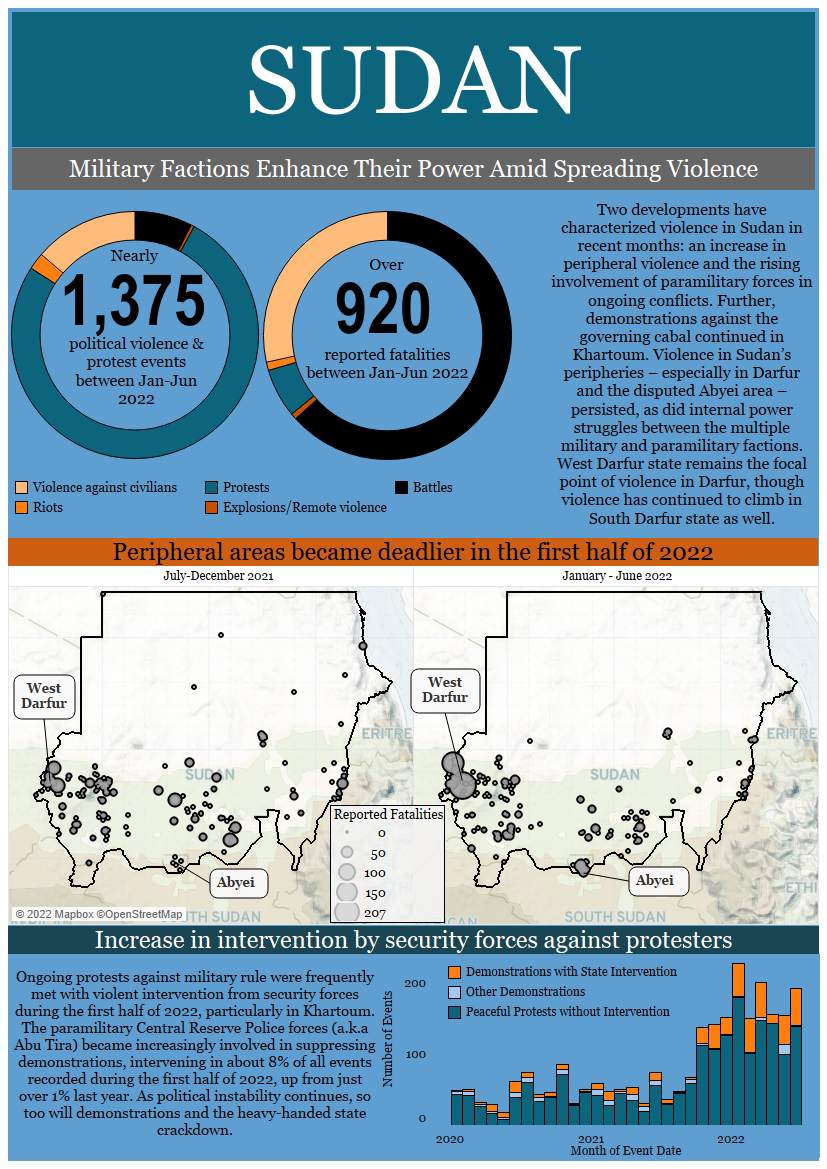

Sudan continues to face intersecting political and economic challenges in 2022, coinciding with increased violence involving paramilitary forces in peripheral areas as well as ongoing anti-government demonstrations in Khartoum. Violence intensified in the peripheries during the first half of the year, especially in Darfur and the disputed Abyei area, as did internal power struggles between elements of the army and paramilitary elites, such as Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti (Africa Confidential, 12 May 2022; Tubiana, 2022). Since the coup in October 2021, the military and paramilitary elite have struggled to maintain order as Sudan’s economic free-fall and hunger crisis continue unabated (Radio Dabanga, 27 June 2022).

Demonstrations against military rule and the worsening economic outlook have compounded Sudan’s political and economic gridlock. Despite domestic and international initiatives to resolve the political turmoil, leftist factions – including Resistance Committees and the Sudanese Communist Party – have refused to participate (United Nations Security Council, 2022), insisting that the military step down from power (Sudan Tribune, 11 May 2022). Demonstrations have escalated in the greater Khartoum area in 2022, where Resistance Committees made numerous attempts to organize marches to the Republican Palace. Security forces have often responded with violence and obstructed processions with barbed wire, concrete barriers, and shipping containers (The National, 25 December 2021). In the first six months of 2022, events where state forces used excessive force against protesters nearly tripled compared to the entirety of 2021. During this period, almost 50 demonstrators were reportedly killed by state forces. Amid the violence, Resistance Committees have declared that protests will continue, regardless of the negotiations between the military and more moderate political factions (Resistance Committees, 8 June 2022).

The rise in political violence across provincial areas is most apparent in Abyei and Darfur, and more recently in Blue Nile. In Abyei, political violence events more than tripled in the first half of 2022 compared to all of last year, driven by reciprocal attacks between Misseriya and Ngok Dinka militias, with Ngok Dinka civilians bearing the brunt of the violence. In February, fighting also broke out between the Ngok Dinka and Twic Dinka from South Sudan, who have been clashing over a previously dormant territorial dispute (Ayin Network, 10 March 2022). These events have contributed to a sevenfold increase in fatalities in Abyei in the first half of 2022 compared to the entirety of 2021. More recently, in mid-July, heavy fighting between the Hausa and Berta1Some reports state that the violence is between the Hausa and the Hamaj groups (e.g. Middle East Eye, 18 July 2022), although there is ambiguity on this point. ethnic groups broke out across multiple locations in Blue Nile state, killing at least 97 people and wounding over 100. The fighting followed escalating tensions and ethnic polarization over an attempt by the Hausa leader in Blue Nile to establish an emirate within the state (BBC News, 24 July 2022).

In Darfur, fighting has frequently involved Arab-identifying militias who are often supported by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) (People’s Dispatch, 5 May 2022). In South Darfur, fighting resumed between Arab-identifying Rizeigat and Fulani (a.k.a. Fellata) pastoralist militias in late March, with fatality estimates ranging from dozens to hundreds. In West Darfur, conflict escalated in April when Rizeigat militias and Masalit militias clashed in Al Kereinik camp of West Darfur, resulting in over 200 fatalities. At least 126 people also reportedly died in early June during clashes between a Rizeigat pastoralist militia and the Qamar in Kulbus locality. Elsewhere, the monthly average number of battle events has slightly decreased across North, South, and West Kordofan states, despite ongoing tensions relating to the Juba Peace Agreement (Rift Valley Institute, 2022b: 4-5).

Meanwhile, renewed fighting broke out between Sudanese and Ethiopian forces over the disputed Al Fashaga region, despite indications earlier in the year of improving relations between the two countries. In June, Ethiopian forces killed Sudanese soldiers and a Sudanese civilian, leading to the Sudanese army attacking several Ethiopian outposts in the disputed area and seizing the stronghold of Barakhat (Radio Dabanga, 28 June 2022; Sudan Tribune, 28 June 2022). The following week, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed met with the Head of Sudan’s Sovereign Council, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and announced efforts to resolve the border dispute (Sudan Tribune, 5 July 2022).

Political volatility and violent disorder are likely to continue throughout the remainder of 2022. While Burhan offered to step back from politics and allow the opposition to form a new interim ‘technocratic’ cabinet, skeptics say the move may divide opposition groups and permit the military to retain control over critical economic and security institutions (Ayin Network, 5 July 2022; Al Jazeera, 6 July 2022). Ongoing political turbulence may allow paramilitary forces opportunities to further consolidate their power, including in central areas of the country. Further, the paramilitary Central Reserve Police forces (also known as Abu Tira) became increasingly involved in suppressing demonstrations, intervening in about 8% of all events recorded during the first half of 2022, up from just over 1% last year. The RSF, meanwhile, may consolidate further links with Russia after Hemedti supported the Ukraine invasion and reportedly deepened ties to Wagner Group mercenaries (New York Times, 5 June 2022).

Such instability is likely to compound the current hunger crisis in Sudan (Thomas and de Waal, 2022). However, discord in Khartoum may not straightforwardly affect violence in the peripheries. Although severe instances of violence in provincial areas primarily represent a continuation of dynamics that have been in effect since late 2019, patterns of violence appear increasingly desynchronized from developments in the capital (for more information on the relationship between core and peripheral violence, see ACLED’s report Riders on the Storm). Instead of provincial violence being animated by the national-level Juba Peace Agreement, as was often the case in 2020, it increasingly takes the form of subnational power struggles between contending local political elites and militias. The violence is typically driven by efforts to establish local territorial control or forcefully assert authority, and no longer appears to be coordinated with an eye toward securing a seat at the table in Khartoum. Moreover, non-Arab groups are increasingly arming themselves, permitting sustained clashes against other armed groups (Rift Valley Institute, 2022a: 3; Tubiana, 2022), indicating that more intensive rounds of fighting and retaliation may be imminent. In the event of a collapse in the working relationship between the military and paramilitary elite, the ingredients are in place for these complex local power struggles to become subsumed within the overarching rivalries between the central players in the military bloc.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s protests and riots event types.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and twenty-five types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riot event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type as well as specific explosions/remote violence events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.