10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Lebanon

Mid-Year Update

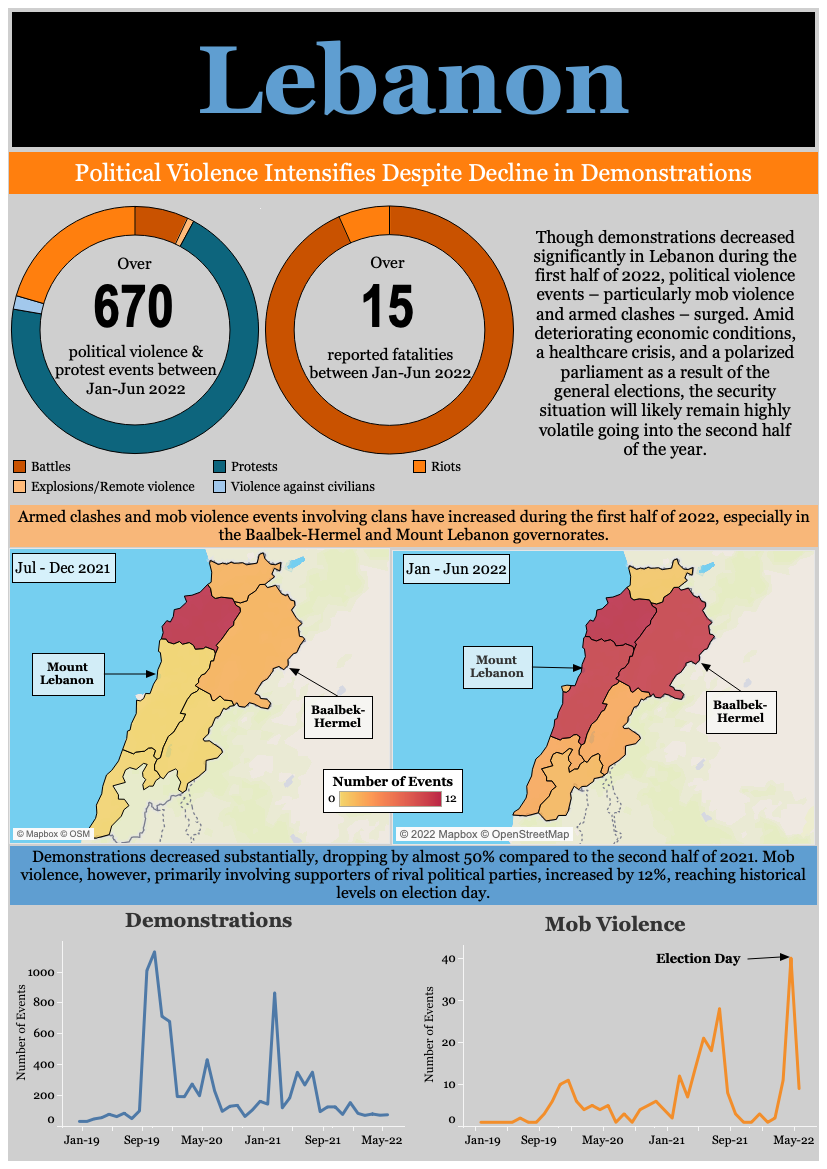

Political Violence Intensifies Despite Decline in Demonstrations

Despite a sharp decrease in demonstrations compared to the year prior, political violence events – particularly mob violence and armed clashes – increased in Lebanon during the first half of 2022. While the Central Bank’s intervention in the currency market, as well as pre-election and geopolitical dynamics, may have contributed to the decline in demonstrations, election-related tensions and clan disputes amid the country’s deteriorating socio-economic situation have likely spurred the concomitant rise in violence. Key reforms to unlock much-needed funding from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to alleviate Lebanon’s economic woes are unlikely to be implemented by the end of the year due to the persistent political paralysis and deep-rooted corruption that continue to threaten stability in the country.

Almost three years into an economic and financial crisis – among the world’s worst in recent centuries (World Bank, 1 June 2021) – Lebanon continues to grapple with harsh economic conditions. In March, the inflation rate surpassed 200% and hit a three-month high in May (IFRC, 15 May 2022). At the same time, the war in Ukraine has exacerbated the food shortage, as Lebanon relies on Russia and Ukraine for over 80% of its wheat supply (Deutsche Welle, 26 April 2022).

Amid the worsening economic climate and parliamentary elections held in May, the number of demonstration events in Lebanon decreased by 50% in the first six months of 2022 compared to the six months prior. Several factors have likely contributed to this decline. The anti-government protest movement – which initially emerged in 2019 to demand reforms and accountability – increasingly moved its fight from the street to the ballot box. Thirteen candidates hailing from the protest movement and civil society, referred to as the ‘change opposition,’ won seats in the 128-member parliament (USIP, 19 May 2022). Although power remains firmly in the hands of the traditional ruling establishment, the outcome of the elections may have restored some hope among Lebanese seeking political reform.

Furthermore, Lebanese society has historically turned to the traditional establishment parties, as well as their clientelist and patronage networks, in times of crisis to ensure economic survival (USIP, 19 May 2022). In the lead-up to the election, establishment parties increasingly used patronage to secure support and to buy votes, which provided some relief to the most economically vulnerable (Orient XXI, 31 May 2022). Moreover, the Central Bank made the political decision to intervene in the market several times during the first six months of 2022 to strengthen Lebanon’s currency amid fears of social unrest (Arab News, 27 May 2022). Additionally, while tourists and much of the Lebanese diaspora have stayed away from Lebanon in recent years following the 2020 Beirut port explosion and the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism is now returning to the country, providing a much-needed cash injection (New Arab, 22 June 2022).

A certain level of de-escalation at the regional level may also have eased some of Lebanon’s domestic tensions. Unrest related to the investigations of the Beirut port explosion reached a peak in the second half of 2021, resulting in over 70 demonstration events. Tensions also led to a deadly armed clash between supporters of Iran-backed Shiite Hezbollah and the Amal movement, on one side, and Saudi-backed Christian Lebanese Forces on the other. In the first half of 2022, however, the issue has been deprioritized in political discourse and investigations have stalled (Amnesty International, 7 June 2022). This shift has occurred parallel to regional developments, including talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia, as well as Hezbollah’s reported role in facilitating the truce in Yemen (Middle East Eye, 27 June 2022). The number of demonstration events over the port explosion declined by more than 75% in the first six months of 2022 compared to the six months prior.

Despite the overall decrease, some groups have intensified demonstration activity in 2022. Notably, demonstrations involving health workers have steadily risen, with a 30% increase in the first half of 2022 compared to the six months prior, and a 70% increase when compared to the first half of 2021. Nearly 40% of Lebanon’s doctors and 30% of nurses have left the country since October 2019 (WHO, 19 September 2022), as healthcare workers were hit especially hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only did the crisis leave many overworked and underpaid, but pandemic-related closures also resulted in the gradual attrition of highly skilled specialists (The Lancet, 17 November 2021). Healthcare workers are “reaching a breaking point,” as those who have stayed remain overworked and underpaid, and the value of their salaries has fallen with the devaluation of the currency (The National, 7 June 2022).

Meanwhile, the number of mob violence incidents and armed clash events in Lebanon increased by nearly 15% in the first half of 2022 compared to the six months prior. Mob violence spiked during the election in May, with election day seeing the highest number of mob violence events recorded on a single day since the start of ACLED’s coverage of Lebanon in 2016 (for more, see ACLED’s infographic on election-related political violence in Lebanon). Supporters of Hezbollah and its allies in the Amal Movement and the Free Patriotic Movement, as well as rival supporters of the Lebanese Forces, were together involved in half of all mob violence events on election day. While mob violence events most often involved supporters of rival parties, rioters also attacked election officials, observers, candidates, and journalists.

Violence involving clan groups and militias has also been on rise in Lebanon in 2022. Armed clashes and mob violence events involving clans increased by almost 20% during the first half of the year compared to the six months prior. Well-armed clan militias involved in drug trafficking and counterfeiting have traditionally controlled many economically depressed areas in Lebanon (Search for Common Grounds, July 2020). This includes the Baalbek-Hermel governorate, which has registered the highest number of armed clashes so far in 2022. Deteriorating economic conditions have compounded the problems, with localized conflicts intensifying as expanding smuggling activities have revived old disputes, such as access to land (The National, 20 January 2021). Rising social tensions along with increased violence and crime rates have left Lebanon’s security forces particularly overburdened, while personnel no longer earn living wages (Global Risks Insight, 8 July 2021). This has likely led to a further decline in state presence in the tribal areas where clan militias operate (The National, 20 January 2021).1While ACLED does not track criminal violence, in the case of Lebanon, the unique structure of the political system and the role of clans in that system necessitates the tracking of inter-clan armed clashes, despite clans’ involvement in criminal activities.

The security situation in Lebanon remains highly volatile. Obstacles to the formation of a new government, complicated by a sharply polarized parliament and no single bloc with a clear majority, will likely delay reforms necessary to unlock financial aid. The protracted political paralysis already plaguing the country may be exacerbated in late 2022 when the parliament will have to elect a new president, potentially aggravating the country’s socio-economic tensions. But even if the Lebanese government were to pass reform laws, the prospects of the ruling elite following through with real changes are slim. Elites will likely proceed with their strategy of “deliberate delay” rather than effectively address the drivers of the current crisis in order to defend their vested interests, wealth, and power (World Bank, 30 May 2022). Average citizens will continue to pay the price.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s protests and riots event types.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and twenty-five types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riot event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type as well as specific explosions/remote violence events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.