ACLED 2021

The Year in Review

Published: 8 March 2022

ACLED’s 2021 annual report reviews the past year of data on political violence and demonstration activity around the world.

Executive Summary

Few conflicts ended in 2021, and many intensified. Overall levels of political violence remained steady, while its lethality surged to new heights. Civilians bore the brunt, with increases in both violence targeting civilians and civilian fatalities. Where conflict declined last year, fragile ceasefires often obscured the growing risk of escalation — now seen in Yemen and Ukraine. Where long wars ended, such as in Afghanistan, new risks have emerged for civilians.

Against this backdrop, social unrest continued to build during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a rise in demonstrations all around the world from rallies against public health restrictions to mass pro-democracy protest movements. Authorities responded violently in places like Myanmar and Colombia, leading to a spike in demonstrator fatalities.

As the world struggles to come to grips with a third year of the pandemic — as well as the potentially devastating consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — global insecurity is likely to only deepen and evolve throughout 2022 (for more, see ACLED’s special report on 10 additional conflicts worry about).

Over the course of 2021 and early 2022, ACLED expanded to Canada, Oceania, Antarctica, and all remaining small states and territories, bringing the dataset to full global coverage. Our 2021 annual report reviews the past 12 months of data on political violence and demonstration activity around the world. Key findings are outlined below.

Note de synthèse

Rares sont les conflits qui ont pris fin, et nombreux sont ceux qui se sont aggravés en 2021. Si le niveau général de violence politique est resté stable, sa létalité, elle, a atteint de nouveaux sommets. Les civils en ont été les principales victimes, du fait d’une augmentation des violences dirigées contre eux et du nombre de morts au sein de leur population. L’an dernier, là où les conflits ont reculé, des cessez-le-feu précaires ont souvent dissimulé un risque croissant d’escalade, comme on l’observe actuellement au Yémen et en Ukraine. À l’inverse, là où de longues guerres ont pris fin, comme en Afghanistan, de nouvelles menaces sont apparues pour les civils.

Dans ce contexte, l’agitation sociale a continué de s’accroître tout au long de la deuxième année de pandémie de Covid-19, marquée par une hausse des manifestations dans le monde entier, qu’il s’agisse de rassemblements contre les restrictions en matière de santé publique ou de mouvements de contestation massifs en faveur de la démocratie. Dans des pays tels que le Myanmar et la Colombie, les autorités y ont répondu avec violence, entraînant un pic de mortalité auprès des manifestants y ayant pris part.

Alors que le monde entame sa troisième année aux prises avec la pandémie – et fait désormais face aux conséquences potentiellement dévastatrices de l’invasion de l’Ukraine par la Russie (voir le pôle de recherche mis en place par ACLED à cet effet – contenu non traduit) – l’insécurité mondiale risque de s’aggraver et de s’amplifier en 2022 (pour en savoir plus, voir le rapport spécial d’ACLED sur 10 conflits supplémentaires à surveiller dans le monde en 2022 – non traduit).

Au cours de l’année 2021 et au début de l’année 2022, ACLED a étendu sa collecte de données au Canada, à l’Océanie, à l’Antarctique et au reste des petits États et régions du monde, atteignant une couverture totale du globe. Notre rapport annuel de 2021 passe en revue les données des 12 derniers mois sur les actes de violence politique et les manifestations dans le monde. Les principales observations qui en découlent sont exposées ci-dessous.

Resumen ejecutivo

En 2021, pocos conflictos terminaron y muchos se intensificaron. Los niveles generales de violencia política se mantuvieron estables, mientras que su letalidad aumentó, alcanzando nuevas alturas. Las poblaciones civiles se llevaron la peor parte, con aumentos tanto en la violencia contra ellos como en el número de muertes. En donde el conflicto menguó, los frágiles altos al fuego escondían a menudo, un creciente riesgo de escalada, como ahora se ve en Yemen y Ucrania. En donde terminaron largas guerras, por ejemplo en Afganistán, han surgido nuevos riesgos para los civiles.

En este contexto, el malestar social continuó creciendo a lo largo del segundo año de la pandemia de COVID-19. Aumentaron las manifestaciones en todo el mundo, que van desde demostraciones contra las restricciones de salud pública hasta movimientos masivos de protesta a favor de la democracia. Las autoridades respondieron violentamente en lugares como Myanmar y Colombia, lo que provocó un aumento en las muertes de manifestantes.

A medida que el mundo enfrenta un tercer año de pandemia y las consecuencias devastadoras que potencialmente dejará la invasión rusa a Ucrania,es probable que la inseguridad global solo se profundice y evolucione en 2022 (para obtener más información, consulte el Informe Especial de ACLED sobre 10 conflictos adicionales que preocupan en 2022).

En el transcurso de 2021 y principios de 2022, ACLED se expandió a Canadá, Oceanía, Antártida y todos los pequeños estados y territorios restantes, llevando el conjunto de datos a una cobertura global completa. Nuestro informe anual de 2021 revisa los últimos 12 meses de datos sobre violencia política y actividad de manifestación en todo el mundo. A continuación, se describen algunas de las principales conclusiones.

Key Findings

Political violence remained at similar levels relative to 2020. Political violence decreased by less than 2% — or 1,449 events — in 2021. In total, ACLED records 94,833 political violence events in 2020 and 93,384 in 2021. While regions like Central Asia and the Caucasus, Europe, and South Asia experienced significant decreases in violence, Southeast Asia saw an increase of 190%, driven by the military coup and ensuing crisis in Myanmar.

Reported fatalities rose significantly. Fatalities from political violence increased by 12% — or 15,740 deaths — compared to 2020. In total, ACLED records 131,370 fatalities in 2020 and 147,110 in 2021. Political violence was deadlier in 2021 in every region except for Europe and the Middle East. Fatalities in Central Asia and the Caucasus increased by more than 11%, despite a decrease in political violence events.

Civilian targeting and civilian fatalities increased. In 2021, civilians were more frequently targeted by political violence than in 2020, with far deadlier consequences. ACLED records a 12% increase in civilian targeting overall last year, with 33,331 events reported in 2020 compared to 37,185 in 2021. Civilian fatalities too increased by 8%, with 35,889 reported fatalities in 2020 compared to 38,658 in 2021. The greatest increases in civilian targeting were recorded in Myanmar, Palestine, Colombia, Nigeria, and Burkina Faso.

Anonymous armed groups, as well as state forces, remained the most active perpetrators of violence targeting civilians. For the second consecutive year, anonymous or unidentified armed, organized groups top the list of most active perpetrators of civilian targeting, responsible for the largest proportion at 45% of all events reported in 2021. Of identified actors, state forces continued to pose the greatest threat to civilians last year, responsible for 16% of civilian targeting and 14% of civilian fatalities.

Despite the continued rise of violent non-state actors, including rebel groups and political militias, state forces remained the most active conflict agents. While overall state engagement in political violence fell substantially — by 18% or 10,195 events — for the second year, state forces remained the dominant conflict agents globally. State forces engaged in 46% of all political violence events in 2021.

Ceasefires obscured persistent fragility in 2021. The greatest decreases in political violence took place in contexts where ceasefires and power-sharing agreements were reached in 2020 and early 2021. These include: Azerbaijan and Armenia over the breakaway Artsakh Republic1The disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan. ACLED refers to the de facto state and its institutions as Artsakh — the name by which the de facto territory refers to itself. For more on methodology and coding decisions around de facto states, see this methodology primer.; Ukraine and Russian-aligned separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk; Pakistan and India along the disputed Line of Control (LoC); and rival governments in Libya. Similarly, in Yemen, a decrease in violence in 2021 was driven by the formation of a power-sharing cabinet between the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and the Hadi government in the southern governorates in late 2020, alongside international engagement in peace negotiations on the Houthi conflict. Despite the declines in violence, each context remains deeply fragile and susceptible to further outbreaks of violence. In both Yemen and Ukraine, this fragility was readily apparent as fighting continued throughout 2021 and ultimately escalated in early 2022.

Demonstration activity continued to increase in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Demonstrations rose by 9% — or 13,104 events — in 2021, compared with 2020. While this growth was driven by a range of movements, mass anti-government demonstrations were particularly prominent in those countries that registered the greatest increases in demonstration activity. These included mass demonstrations against health, education, social, and economic policies in Colombia; anti-coup demonstrations in Myanmar; water and wage-related demonstrations in Iran; and, demonstration movements against COVID-19 restrictions in France and Italy.

Observations principales

Les actes de violence politique se sont maintenus à des niveaux équivalents à ceux de 2020. Les actes de violence politique ont affiché une diminution de moins de 2% (soit 1 449 événements de moins) en 2021. Au total, ACLED recense 94 833 événements liés à des actes de violence politique pour l’année 2020, contre 93 384 pour 2021. Si des régions telles que l’Asie centrale et le Caucase, l’Europe et l’Asie du Sud ont connu une baisse significative de ces faits de violence, l’Asie du Sud-Est, elle, a vu leur nombre croître de 190%. Une augmentation portée en grande partie par le coup d’État militaire au Myanmar et par la crise y ayant fait suite.

Le nombre de morts signalées a considérablement augmenté. Les morts attribuables à des actes de violence politique ont grimpé de 12% (soit 15 740 décès supplémentaires) par rapport à 2020. Au total, ACLED dénombre 131 370 décès pour l’année 2020, contre 147 110 pour 2021. Les actes de violence politique se sont ainsi avérés davantage meurtriers dans toutes les régions du monde à l’exception de l’Europe et du Moyen-Orient en 2021. En Asie centrale et dans le Caucase, le nombre de morts a connu une hausse de 11%, et ce malgré une diminution des événements liés à des actes de violence politique.

Les actions visant des civils et les morts au sein des populations civiles ont augmenté. En 2021, les civils ont été plus fréquemment visés par des actes de violence politique qu’en 2020, et ce avec des effets nettement plus meurtriers. Sur l’ensemble des données enregistrées l’année dernière, ACLED relève une augmentation de 12% des actions visant des civils, avec 33 331 événements signalés en 2020 contre 37 185 en 2021. Avec une hausse de 8%, les morts au sein des populations civiles ont, elles aussi, augmenté. Cela se traduit par 35 889 décès signalés en 2020, contre 38 658 en 2021. Les plus fortes hausses en termes d’actions visant des civils ont été observées au Myanmar, en Palestine, en Colombie, au Nigéria et au Burkina Faso.

Les groupes armés et organisés anonymes, ainsi que les forces étatiques, demeurent les acteurs les plus actifs de violences contre les civils. Pour la deuxième année consécutive, les groupes armés et organisés anonymes ou non-identifiés arrivent en tête du classement du nombre d’actions commises contre des civils, se rendant responsables de la part la plus importante (soit 46%) de l’ensemble des actions de ce type recensées en 2021. Parmi les groupes armés et organisés identifiés, les forces étatiques continuaient de représenter la principale menace pour les civils l’année dernière, ayant été impliqués dans 16% des actions visant des civils et dans 14% des décès enregistrés au sein de cette même population.

Malgré la progression constante d’acteurs non-étatiques violents, parmi lesquels des groupes rebelles et des milices politiques, les forces étatiques sont restées les agents de conflit les plus actifs. Quoique l’implication globale des États dans des actes de violence politique ait considérablement reculé (de 18%, soit 10 195 événements de moins) pour la deuxième année consécutive, les forces étatiques ont continué d’être les principaux agents de conflit dans le monde. Celles-ci étaient ainsi impliquées dans 46% du total des événements liés à des faits de violence politique en 2021.

Les accords de cessez-le-feu ont masqué des fragilités persistantes en 2021. Les plus fortes baisses en termes d’actes de violence politique ont été recensées dans des zones où des cessez-le-feu et des accords de partage du pouvoir ont été conclus en 2020 et début 2021. Il s’agit notamment : de l’Azerbaïdjan et de l’Arménie, autour de la question de la république séparatiste d’Artsakh2Le territoire contesté du Nagorno-Karabakh est reconnu internationalement comme faisant partie de l’Azerbaïdjan. ACLED désigne cet État de facto et ses institutions sous le nom d’Artsakh – appellation par laquelle le territoire de facto se désigne lui-même. Pour en savoir plus sur la méthodologie et les choix de codage concernant les États de facto, se référer à ce guide méthodologique (non traduit). ; de l’Ukraine et des territoires séparatistes pro-russes de Donetsk et de Lougansk ; du Pakistan et de l’Inde le long de la ligne de contrôle (Line of Control (LoC) en anglais) contestée ; et des gouvernements rivaux en Libye. De la même manière, au Yémen, la diminution des violences observée en 2021 est due en grande partie à la formation, fin 2020, d’un gouvernement de partage du pouvoir entre le Conseil de transition du Sud (CTS) (Southern Transitional Council (STC) en anglais) et le gouvernement Hadi dans les gouvernorats du sud du pays, conjointement à l’engagement international dans les négociations de paix sur le conflit avec les Houthistes. Malgré le recul de la violence, chacun de ces contextes reste profondément fragile et susceptible de connaître de nouvelles flambées de violence. Au Yémen et en Ukraine, cette fragilité est apparue au grand jour avec la poursuite des combats tout au long de l’année 2021 et leur escalade début 2022.

Le nombre de manifestations a continué d’augmenter au cours de la deuxième année de pandémie de Covid-19. Par rapport à 2020, les manifestations ont progressé de 9% (soit 13 104 événements supplémentaires) en 2021. Si cette tendance a été portée par un large éventail de mouvements, les manifestations antigouvernementales de masse ont été particulièrement saillantes dans les pays ayant enregistré la plus forte augmentation du nombre de manifestations sur leur territoire. Celles-ci comprenaient notamment des manifestations de masse contre les politiques sanitaires, éducatives, sociales et économiques en Colombie ; des manifestations contre le coup d’État au Myanmar ; des manifestations liées à l’eau et aux salaires en Iran ; et des mouvements de contestation contre les restrictions sanitaires liées au Covid-19 en France et en Italie.

Principales conclusiones

La violencia política se mantuvo en niveles similares en relación con 2020. La violencia política disminuyó en menos del 2 %, o 1.449 eventos, en 2021. En total, ACLED registra 94,833 eventos de violencia política en 2020 y 93,384 en 2021. Mientras que regiones como Asia Central y el Cáucaso, Europa y el sur de Asia experimentaron disminuciones significativas en la violencia, el sudeste asiático experimentó un aumento del 190 %, impulsado por el golpe militar y la consiguiente crisis en Myanmar.

Las muertes reportadas aumentaron significativamente. Las muertes por violencia política aumentaron en un 12 %, o 15,740 muertes, en comparación con 2020. En total, ACLED registra 131,370 muertes en 2020 y 147,110 en 2021. La violencia política fue más mortífera en 2021 en todas las regiones, excepto en Europa y Oriente Medio. Las muertes en Asia Central y el Cáucaso aumentaron en más del 11 %, a pesar de una disminución en los eventos de violencia política.

Los ataques y las muertes de civiles aumentaron. En 2021, los civiles fueron blanco de la violencia política con mayor frecuencia que en 2020, con consecuencias mucho más mortíferas. ACLED registra un aumento del 12 % en los ataques civiles en general el año pasado, con 33,331 eventos reportados en 2020 en comparación con 37,185 en 2021. Las muertes civiles también aumentaron en un 8 %, con 35,889 muertes reportadas en 2020 en comparación con 38,658 en 2021. Los mayores aumentos en los ataques contra civiles se registraron en Myanmar, Palestina, Colombia, Nigeria y Burkina Faso.

Los grupos armados y organizados anónimos, así como las fuerzas estatales, siguen siendo los perpetradores más activos de la violencia contra poblaciones civiles. Por segundo año consecutivo, los grupos armados y organizados anónimos o no identificados encabezan la lista de los perpetradores más activos de ataques contra civiles, responsables de la mayor proporción, con el 46 % de todos los eventos reportados en 2021. De los actores identificados, las fuerzas estatales continuaron representando la mayor amenaza para los civiles el año pasado, responsables del 16 % de los ataques contra civiles y el 14 % de las muertes de población civil.

A pesar del continuo aumento de actores no estatales violentos, incluidos los grupos rebeldes y las milicias políticas, las fuerzas estatales siguieron siendo los agentes de conflicto más activos. Si bien la participación general del Estado en la violencia política se redujo sustancialmente, en un 18 % o 10.195 eventos— por segundo año, las fuerzas estatales siguieron siendo los agentes de conflicto dominantes a nivel mundial. Las fuerzas estatales participaron en el 46 % de todos los eventos de violencia política en 2021.

Los ceses al fuego menguaron la fragilidad persistente en 2021. Las mayores disminuciones de la violencia política tuvieron lugar en contextos en los que se alcanzaron ceses al fuego y acuerdos de reparto de poder en 2020 y principios de 2021. Estos incluyen: Azerbaiyán y Armenia sobre la República separatista de Artsaj;3El territorio en disputa de Nagorno Karabaj es reconocido internacionalmente como parte de Azerbaiyán. ACLED se refiere al estado de facto y sus instituciones como Artsaj, el nombre con el que el territorio de facto se refiere a sí mismo. Para obtener más información sobre la metodología y las decisiones de codificación en torno a los estados de facto, consulte este manual de metodología. Ucrania y los separatistas alineados con Rusia en Donetsk y Lugansk; Pakistán e India a lo largo de la disputada Línea de Control (LoC), y gobiernos rivales en Libia. Del mismo modo, en Yemen, una disminución de la violencia en 2021 fue impulsada por la formación de un gabinete de poder compartido entre el Consejo de Transición del Sur (STC) y el gobierno de Hadi en las gobernaciones del sur a fines de 2020, junto con la participación internacional en las negociaciones de paz sobre el conflicto Hutí. A pesar de la disminución de la violencia, cada contexto sigue siendo profundamente frágil y susceptible a nuevos brotes de violencia. Tanto en Yemen como en Ucrania, esta fragilidad fue evidente a medida que los combates continuaron a lo largo de 2021 y finalmente se intensificaron a principios de 2022.

La actividad de demostración continuó aumentando en el segundo año de la pandemia de COVID-19. Las manifestaciones aumentaron un 9 %, o 13.104 eventos, en 2021, en comparación con 2020. Si bien este crecimiento fue impulsado por una serie de movimientos, las manifestaciones masivas contra el gobierno fueron particularmente prominentes en aquellos países que registraron los mayores aumentos en la actividad de manifestación. Estos incluyeron manifestaciones masivas contra las políticas de salud, educación, sociales y económicas en Colombia; manifestaciones contra el golpe de Estado en Myanmar; manifestaciones relacionadas con el agua y los salarios en Irán, y, movimientos de manifestación contra las restricciones de COVID-19 en Francia e Italia.

In this report, the term political violence refers to all events coded with event type Battles, Explosions/Remote violence, and Violence against civilians, as well as all events coded with sub-event type Mob violence under the Riots event type. The latter is included given that this violence, while spontaneous rather than organized, is often similar in nature to violence involving communal groups such as local security providers. Mob violence is more similar to other forms of political violence than it is to violent demonstrations (described below). Including Mob violence within political violence also has the benefit of allowing for a better understanding of the spectrum of political violence and how it may manifest differently across different spaces.

The complement to political violence in the ACLED dataset is the term demonstrations, which is used in this report to describe all events coded with event type Protests, as well as all events coded with sub-event type Violent demonstration under the Riots event type. Expanding on the point raised above, Mob violence is not grouped with demonstrations here because it looks less like other forms of demonstrations associated with mass social movements, and more like political violence. The events included under demonstrations here are what users may typically associate with social movements — in which groups of demonstrators advocate for a certain policy or belief. These demonstrations may be peaceful or violent.4While ACLED collects information on demonstrations, it is important to remember that these are demonstration events. ACLED is an event-based dataset, and therefore only records demonstration events; the number of ‘demonstration events’ recorded by ACLED may differ from the number of ‘demonstrations’ recorded via other methodologies. The number of demonstrations is reliant largely on reporting and the terminology used in doing so. For example, five separate demonstrations happening in Algiers around a single topic within a few blocks of each other may be reported on in a newspaper as “demonstrations happened in Algiers” or “five demonstrations happened in Algiers.” Both are correct in their terminology, but if they are coded differently as a result (1 vs. 5), this would introduce a bias. ACLED codes an event based on an engagement in a specific location (e.g. Algiers) on a specific day in order to avoid such biases. For ease of readability, these events are often referred to solely as demonstrations in this report.

The term disorder is then used in this report to refer to all political violence and demonstrations. This effectively includes all events in the ACLED dataset, minus Strategic developments — which should not be visualized alongside other, systematically coded ACLED event types due to their more subjective nature. For more on Strategic developments and how to use this event type in analysis see this primer.

Following from these, armed organized violence is a subset of political violence, made up of all events coded with event type Battles, Explosions/ Remote violence, and Violence against civilians. The difference between political violence and armed organized violence is that Mob violence is included in the former; it is not included in the latter as this violence is spontaneous in nature (not organized) and often does not include armed individuals.

Both the term conflict and war refer to campaigns of events, rather than specific event types. The ‘war in Yemen’, for example, may include a variety of types of events — Battles, Explosions/Remote violence, and Violence against civilians. These categorizations will hence be denoted on the basis of the actors involved, the location of events (at the country or subnational level), and/or time periods. The distinction between the two terms (conflict and war) is one of scale: the latter is a more intense form of the former. For more on this categorization, see the latter portion of this primer.

Civilian targeting refers to all violence which targets unarmed individuals. It is important to remember that events coded with event type Violence against civilians are only one subset of this violence. Civilians can also be targeted in events coded with event type Explosions/Remote violence and Riots, as can Protesters (i.e. unarmed demonstrators). Protesters can also be targeted through lethal forms of violence in events coded with sub-event type Excessive force against protesters coded under event type Protests.

While ACLED records fatalities, it is important to remember that the set includes reported fatalities. Fatality numbers are frequently the most biased and poorly reported component of conflict data. The totals are often debated and can vary widely. Conflict actors may overstate or under-report fatalities to appear strong to the opposition or to minimize international backlash against the state involved. Fatality counts are also limited by the challenges of collecting exact data mid-conflict. While ACLED codes the most conservative reports of fatality counts to minimize over-counting, this does not account for biases that exist around fatality counts at-large (for more, see: Washington Post, 2 October 2017). While fatality estimates are a telling indicator of how conflict intensity and lethality shift over time, they are generally less reliable than other metrics coded by ACLED, due in part to the highly politicized and varying fatality information reported by different sources. Such a metric is therefore largely used as a supplement to other modes of analysis, and is why it is treated as a measure of reported fatalities, rather than a concrete number. For ease of readability, this report often refers solely to fatalities, but please note that these are references to reported fatalities specifically. For more on ACLED’s methodology around coding fatalities, see this primer.

ACLED in 2021

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) is a disaggregated data collection, analysis, and crisis mapping project that tracks political violence and demonstrations around the world. ACLED is an event-based data project, meaning that each engagement is recorded by date and location. Along with this information, ACLED records the actors, types of violence, and fatalities associated with each event — allowing for a multitude of ways to explore disorder dynamics.

Last year, in addition to continued real-time data coverage, ACLED launched an array of new expansions, special projects, and initiatives to enable users to more closely monitor trends in political violence and protest around the world. ACLED expanded geographic coverage in multiple regions over the course of 2021, extending coverage to all remaining countries in Europe, as well as 13 previously uncovered small states and territories in Africa and Asia. These expansions brought ACLED coverage to more than 200 countries and territories around the world. In ACLED 2021: The Year in Review, we analyze the past year of data on political violence and demonstrations across these new regions of coverage, as well as prior coverage areas, including: Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean, Central Asia and the Caucasus, East Asia, Europe, and the United States.

In early 2022, ACLED achieved global coverage with expansions to Canada, Oceania, Antarctica, and all remaining small states and territories, which extends to the start of 2021. These new areas of coverage are therefore not included in this report’s comparative analysis of 2020 and 2021. However, data on these countries are included in the analysis of specific trends in 2021 and will be included in next year’s annual report comparing trends in 2021 to 2022.

In addition to these geographic expansions, ACLED launched its second observatory, the Ethiopia Peace Observatory (EPO), to enhance local data collection and analysis on political violence and protest trends across Ethiopia. The launch of the EPO follows the launch of Cabo Ligado the year prior, in partnership with Zitamar News and Mediafax, to track the insurgency in Mozambique’s northern Cabo Delgado province.

ACLED also launched an initiative to enable the monitoring of political violence targeting women in politics (PVTWIP) in late 2021. This built on an initial data release on political violence targeting women (PVTW) in partnership with the Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law at The University of Texas at Austin in 2019. ACLED has now expanded the data to introduce identity types for the targets of PVTW, including further detail that specifically enables the tracking of PVTWIP for the first time. The new data and accompanying analysis show that PVTWIP has increased over time in nearly all regions of ACLED coverage.

Moreover, ACLED also launched the Early Warning Research Hub last year.5Following the initial beta launch in 2021, ACLED officially launched an updated and expanded version of the hub in early 2022. The hub provides a suite of interactive resources aimed at supporting data-driven initiatives to anticipate and respond to emerging crises. They include: Subnational Threat & Surge Trackers to track and map subnational conflict spikes; the Volatility & Risk Predictability Index to track the frequency and intensity of conflict surges; the Conflict Change Map to identify countries at risk of rising political violence; and the Emerging Actor Tracker to monitor the proliferation of new non-state actors. As part of this hub, ACLED also expanded its existing project to map territorial control in Syria to cover Yemen. With the release of quarterly updates, this project allows viewers to examine in detail the changing scope, focus, and role of various actors in the Yemen conflict.

As a result of these projects, the ACLED dataset is more detailed, precise, and comprehensive than at any point in the organization’s history — and the latest data shed new light on key trends in global conflict and disorder across 2021.

Global Disorder

Disorder increased by 5% across all regions of ACLED coverage from 2020 to 2021. This overall growth in disorder was driven by increased demonstration activity, as political violence largely held steady, with a slight decline of less than 2%. This marks the second consecutive annual decline in aggregate political violence as well as the second consecutive increase in demonstration activity.

This slight decrease in political violence, however, belies worsening conflict dynamics in many parts of the world. Several regions experienced substantial increases in violence, including Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America. Across these regions, a wide range of dynamics contributed to the worsening violence. In Myanmar, the military coup sparked a violent crackdown and widespread conflict. In Ethiopia and Nigeria, new threats continued to appear and compound existing sources of violence nationwide. In other contexts, existing conflict actors deepened activity, as was the case with Al Shabaab insurgents in Somalia and non-state armed groups in Colombia.

Moreover, political violence also became substantially deadlier in 2021. Fatalities from political violence increased by 12% compared to 2020, with increases in every region save for Europe and the Middle East. This was driven by significant increases in fatalities in Afghanistan, amid the Taliban takeover; in post-coup Myanmar; and in Ethiopia, amid the ongoing Tigray war.

The countries that experienced the most violence in 2020 once again topped the list in 2021: Syria, Yemen, Ukraine, Mexico, and Afghanistan. While nearly all of these countries — except Mexico — registered overall decreases in violence from 2020 to 2021, the fact that they remain the world’s most violent countries points to the entrenched nature of their respective conflicts. In Mexico, gang violence not only continued at levels comparable to an active war zone in 2021, but actually worsened.

In a reversal of previous trends, nearly all types of conflict actors increased their activity overall between 2020 and 2021, except for state forces and external/other forces.6These actors include international organizations, state forces active outside of their main country of operation, private security firms and their armed employees, and hired mercenaries acting independently. Despite this exception, state forces remained the dominant conflict agents globally, engaging in 46% of all political violence in 2021. In 2021, three of the five most active conflict agents around the world were domestic state forces: the Ukrainian military, which regularly exchanged ceasefire violations with separatists in Donbas — also among the most world’s most active groups; the defeated Afghan military; and the Myanmar military, in its attempts to suppress anti-coup resistance. A fourth, the Taliban, transformed from rebel to state forces with their takeover of Afghanistan in August.

The threat that civilians face varies across different spaces, from the risks associated with large-scale conflicts, such as in Syria and Myanmar, to the risks stemming from being caught in the crossfire of gang wars, like in Mexico and Brazil. In some spaces, civilians face concurrent and overlapping threats, as is the case in Nigeria, which is home to persistent mob violence and communal conflict, as well as an Islamist insurgency in the northeast and a separatist conflict in the southeast. The greatest increases in civilian targeting were recorded in Myanmar, Palestine, Colombia, Nigeria, and Burkina Faso.

Overall, civilian targeting rose by 12% across all regions covered by ACLED from 2020 to 2021. For the second consecutive year, anonymous or unidentified groups top the list of most violent perpetrators of civilian targeting, responsible for the largest proportion in 2021, at 45% of all events. Of identified actors, state forces continued to pose the greatest threat to civilians last year, responsible for 16% of civilian targeting and 14% of civilian fatalities. Rioters and violent mobs remained the next most frequent perpetrators of civilian targeting, responsible for 14% of events, though only 3% of civilian fatalities.

Despite widespread attention on the pandemic, climate change, and economic challenges, these important developments actually had little direct effect on conflict trends throughout 2021. At the same time, these challenges did fuel social movements and demonstrations, which increased considerably. However, there are few links between widespread social movements and violent conflicts. Protesters rarely became armed, organized violent groups, but often emerged alongside or in conjunction with these groups as they responded differently to similar challenges. A notable exception to this pattern has been the proliferation of armed resistance to the Myanmar military junta following the coup in February 2021. While anti-coup demonstration activity mushroomed in the immediate aftermath of the coup, it has since been eclipsed by acts of armed resistance. Though the scale of crossover between demonstrators and armed actors in Myanmar remains difficult to gauge, reports suggest that in at least some cases, demonstrators actively transformed their activities from peaceful to armed resistance as a result of the violent response they saw from the military (Al Jazeera, 15 June 2021).

Demonstration activity increased by 9% across all regions covered by ACLED. This growth was driven by a range of movements, including mass anti-government and anti-coup demonstrations in Colombia and Myanmar, respectively; economic-related demonstrations in Iran; and, demonstration movements against COVID-19 restrictions in France and Italy.

ACLED 2021: The Year in Review explores these various trends to better understand the myriad ways in which disorder manifests across countries and contexts.

Political Violence

Trends in Political Violence Patterns

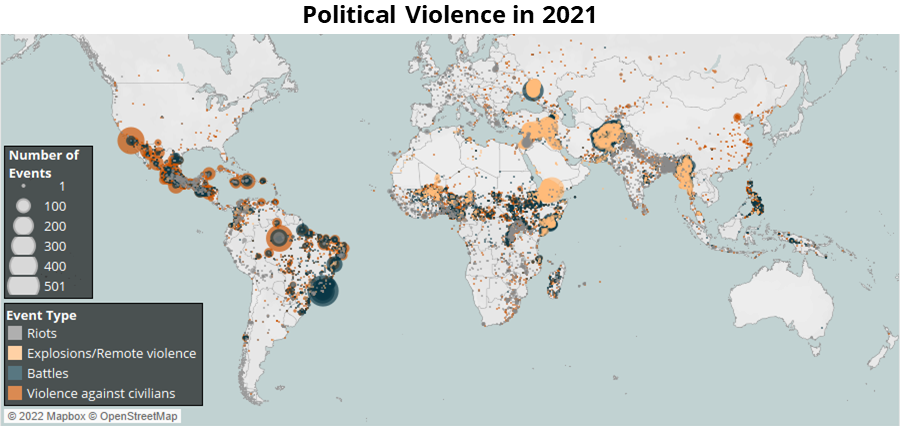

Political violence in 2021 remained at similar levels to 2020, decreasing by less than 2% — or 1,449 events. In total, ACLED records 94,833 political violence events in 2020 and 93,384 in 2021 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Political violence in 2021

While global political violence declined marginally when compared with 2020, several regions experienced significant increases in 2021 (see Figure 2).7Political violence events in the United States total fewer than 300 events across both 2020 and 2021, resulting in very small representation on the chart. Per the Glossary, ‘political violence’ refers to all events coded with event type Battles, Explosions/Remote violence, and Violence against civilians, as well as all events coded with sub-event type Mob violence under the Riots event type. The majority of violence in the United States occurs within the context of Violent demonstrations, which is included within ‘demonstration,’ per the Glossary. ACLED has recently extended coverage of North America to include countries other than the United States. The coverage for these countries spans to the start of 2021. As a result, comparisons between 2020 and 2021 here only include the United States; in next year’s annual report comparing 2021 to 2022, the North American region will be reviewed instead of the United States exclusively. The largest absolute increase was reported in Southeast Asia, which saw a rise of 5,425 events — or 190% — driven by post-coup conflict in Myanmar. This was followed by significant increases in Africa, amid worsening violence in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Nigeria; and South America, pushed by increased contestation between Colombian non-state armed groups. In contrast, Central Asia and the Caucasus, the Middle East, and Europe experienced absolute decreases in political violence of 5,712 events (37%), 1,485 events (6%), and 1,131 events (12%), respectively.

Figure 2. Political violence by region (2020-2021)

The countries home to the most political violence in 2021 remained the same as those in 2020 and 2019: Syria, Afghanistan, Mexico, Yemen, and Ukraine. While nearly all of these countries — except Mexico — experienced decreases in violence compared to 2020, their continued status as the most violent countries in 2021 point to the entrenched nature of their respective conflicts. In Mexico, not only has gang violence remained at levels akin to an active warzone, but it has in fact worsened in 2021, as gangs increased attacks on civilians in some parts of the country, like in Morelos state. Table 1 describes how political violence in these countries has changed since 2020 and identifies the main drivers of the violence.

Table 1. Countries with the highest number of political violence events in 2021

| Country | Number of recorded events | Change in the number of political events since 2020 | Main event type | Main engagement type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syria | 9,321 | Decrease of 1,000 events, or 10% decline | Explosions/Remote violence | One-sided violence involving state forces |

| Afghanistan | 9,004 | Decrease of 747 events, or 8% decline | Battles | Afghan military vs. Taliban |

| Mexico | 7,432 | Increase of 177 events, or 2% rise | Violence against civilians | Gangs targeting civilians |

| Yemen | 7,346 | Decrease of 2,671 events, or 27% decline | Explosions/Remote violence | Saudi-backed Hadi forces vs. Houthi forces |

| Ukraine | 7,290 | Decrease of 1,144 events, or 14% decline | Explosions/Remote violence | Ukrainian government forces vs. Russian-led separatists |

Table 2 presents the countries that experienced the largest decreases in political violence in 2021, outlining the changes and their contributing factors. The most significant declines were found in conflicts in which the dominant agents implemented ceasefires in 2020 and early 2021. These include: Azerbaijan and Armenia over the breakaway Artsakh Republic; Ukraine and Russian-aligned separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk; Pakistan and India along the disputed Line of Control (LoC); and rival governments in Libya. Similarly, in Yemen, a decrease in violence in 2021 was driven by the formation of a power-sharing cabinet between the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and the Hadi government in the southern governorates in late 2020, alongside international engagement in peace negotiations on the Houthi conflict. Despite the decreases in political violence in these countries in 2021, each context remains deeply fragile and susceptible to further outbreaks of violence. In both Yemen and Ukraine, this fragility was readily apparent as fighting continued and worsened throughout the course of 2021 and early 2022. In the case of Ukraine, the progressive breakdown of the ceasefire in Donetsk and Luhansk preceded the wider Russian invasion in February 2022.

Table 2. Countries with largest decreases in political violence in 2021

| Country/ies | Change in the number of political events since 2020 | Contributing factors |

|---|---|---|

| Azerbaijan & Armenia | Decrease of 4,996 events, or 94% | Ceasefire agreement. Political violence decreased sharply in Armenia and Azerbaijan last year as both sides largely held to a ceasefire reached in November 2020. The ceasefire ended a six-week war over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh beginning in September 2020. While cross-border violence remained at relatively low levels throughout 2021, escalations in violence were reported between July and August 2021, and again in November 2021, prompting a fresh Russian-mediated ceasefire.

For an overview of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, see ACLED’s special report: Mid-Year Update: 10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2021. |

| Yemen | Decrease of 2,671 events, or 27% | Power-sharing arrangement, international engagement in peace processes, and frozen fronts. A substantial decrease in political violence in 2021 was driven by several factors. The formation of a power-sharing cabinet between the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC) and the Hadi government in December 2020 contributed to a significant decrease in political violence in the southern governorates, particularly in Abyan. Meanwhile, the unprecedented engagement of international actors in support of the peace process in the middle of the year also saw renewed Houthi participation in negotiations. In May and June 2021, political violence dropped to its lowest levels since the Kuwait peace talks in May 2016, before picking up again in the second half of the year. Finally, there was a relative freezing of a number of fronts between Houthi and anti-Houthi forces, as most of the fighting shifted to Marib governorate. This drove substantial decreases in battle events in Ad Dali governorate, Sadah governorate, and Al Jawf governorate.

For more on shifting territorial control in Yemen, see ACLED’s special territorial control mapping project: The State of Yemen. |

| India | Decrease of 1,211 events, or 38% | Ceasefire with Pakistan and reduction in pandemic-related mob violence. The decrease in political violence in 2021 was largely driven by a precipitous fall in cross-border violence involving Indian and Pakistani state forces. This decrease followed India and Pakistan’s declaration of a ceasefire along the Line of Control (LoC) on 25 February, reaffirming the oft-violated 2003 ceasefire agreement. Fears of potential spillover of militant activity from the conflict in Afghanistan have so far not resulted in any increases in fighting between India and Pakistan. Meanwhile, clashes between mobs and state forces enforcing coronavirus restrictions fell in 2021, after the imposition of nationwide restrictions in 2020. While local-level and statewide lockdowns were enforced during the course of 2021, no nationwide lockdown was imposed.

For an overview of tensions leading to the ceasefire between India and Pakistan, see ACLED’s special report: Mid-Year Update: 10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2021. |

| Ukraine | Decrease of 1,144 events, or 14% | Ceasefire agreement. A ceasefire brokered between Ukrainian state forces and Russian-backed separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk in July 2020 carried into 2021, leading to lower levels of political violence throughout most of 2021. This reduction, however, belies the worsening state of conflict in 2021. Fighting steadily worsened since the ceasefire in July 2020, with political violence peaking in November 2021, exceeding levels of political violence at the time of the ceasefire. While violence subsequently fell near the end of 2021, this coincided with the Russian military buildup in the border regions that preceded Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

For more on the conflict in Ukraine, see ACLED’s Ukraine Crisis hub. |

Despite the slight overall decline in violent events last year, several countries experienced significant increases in political violence. The conflict spikes in some of these countries also contributed to the overall increase in fatalities from political violence in 2021 (explored in further detail in the following section). Table 3 presents the countries that registered the greatest increases in violence last year, outlining the changes and their contributing factors.

Table 3. Countries with major increases in recorded number of political violence events, 2021

| Country | Change in the number of political violence events since 2020 | Contributing factors |

|---|---|---|

| Myanmar | Increase of 5,696 events, or 494% | Anti-coup resistance. The sharp increase in political violence in Myanmar in 2021 was driven by the military’s violence against civilians. Myanmar had the highest number of events of state violence against civilians recorded by ACLED in 2021. As the military carried out these attacks on civilians, local communities began to take up arms. Clashes between the military and local defense groups spread across the country. Many such groups aligned themselves with the People’s Defense Force (PDF) under the National Unity Government (NUG) formed by the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), composed of lawmakers elected in the 2020 general elections and subsequently ousted by the military coup. Fighting between the military and ethnic armed groups also increased, particularly in Kachin and Kayin states, where many anti-coup activists took refuge and received combat training.

For more on the anti-coup resistance in Myanmar, see the ACLED analysis piece: Myanmar’s Spring Revolution. |

| Palestine | Increase of 1,156 events, or 125% | May clashes. A dramatic spike in political violence across the West Bank and Gaza in May 2021 propelled Palestine to its most violent year since the start of ACLED coverage in 2016. A number of separate but interrelated incidents in East Jerusalem precipitated the May escalation: namely, Israeli restrictions on worshippers at the Al Aqsa Mosque compound during the month of Ramadan, and the scheduled eviction of Palestinian families from East Jerusalem’s Shaykh Jarrah neighborhood. In response to the intervention of Israeli forces in East Jerusalem, mob violence proliferated as Palestinians clashed with Israeli military forces, as well as far-right Israelis and settler groups. At the same time, Hamas launched attacks on Israel from the Gaza Strip, claiming to operate out of solidarity with Palistinians in the West Bank. This prompted retaliatory attacks on Gaza targets by Israeli forces.

For more on the lead-up to the May clashes in Palestine and Israel see the ACLED-Religion report: Religious Repression During Ramadan. |

| Iraq | Increase of 1,142 events, or 37% | Turkish offensive against the PKK. Turkey continued to push their fight against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) further into Iraq and out of Turkey in 2021. Turkey launched twin operations — ‘Claw-Lightning’ and ‘Claw-Thunderbolt’ — against the PKK in April 2021, resulting in a spike in political violence in Iraqi Kurdistan and the largest number of Turkey-PKK engagements in Iraq since ACLED coverage began in 2016. The offensives were driven by the greater operational presence of Turkish troops on the ground in northern Iraq, with armed clashes and shelling/artillery/missile attacks both increasing as a percentage of total armed engagements between Turkish forces and the PKK in 2021.

For more on the Turkish offensive in Iraq against the PKK, see the ACLED analysis piece: Turkey-PKK Conflict: Rising Violence in Northern Iraq. |

| Ethiopia | Increase of 891 events, or 161% | The Tigray conflict, regional insurgencies, and ethnic violence. The outbreak of the Tigray war between the Ethiopian federal government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) — and the later established Tigray Defence Forces (TDF) — in November 2020 drove a dramatic increase in political violence in 2021. Fighting between TPLF/TDF forces and Ethiopian state forces operating alongside regional forces continued throughout the year, shifting between the Tigray, Amhara, and Afar regions. The conflict also led to the proliferation of mass killings and sexual violence targeting civilian groups by all sides. While the majority of international focus remains squarely on heavy fighting in the north, anti-government insurgencies and communal violence have also spread across the country, further driving the increase in political violence in 2021. Anti-government militants have been active in Oromia; Benshangul/Gumuz; the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Region (SNNPR); and Amhara in 2021, with ethnic militias active across multiple areas of contested territory.

For more on ongoing conflicts in Ethiopia, see ACLED’s Ethiopia Peace Observatory. |

| Burkina Faso | Increase of 663 events, or 100% | Resurgent Islamist insurgency and worsening inter-ethnic conflict. The breakdown of negotiations between Burkina Faso’s government and the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) in late 2020 drove a resurgence of JNIM activity in 2021. In response, state forces increased counter-insurgency operations, further driving up political violence and triggering counterattacks by militants. At the same time, JNIM militants and Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP) fighters carried out ethnically motivated tit-for-tat attacks on civilian populations, with VDP fighters launching multiple attacks on Fulani communities. Meanwhile, resurgent military activity in Mali in the latter half of 2021 pushed militants across the border into Burkina Faso, further exacerbating political violence in the country.

For more on the ongoing insurgency in Burkina Faso, see the ACLED report: Sahel 2021: Communal Wars, Broken Ceasefires, and Shifting Frontlines. |

Trends in Reported Fatalities Stemming from Political Violence

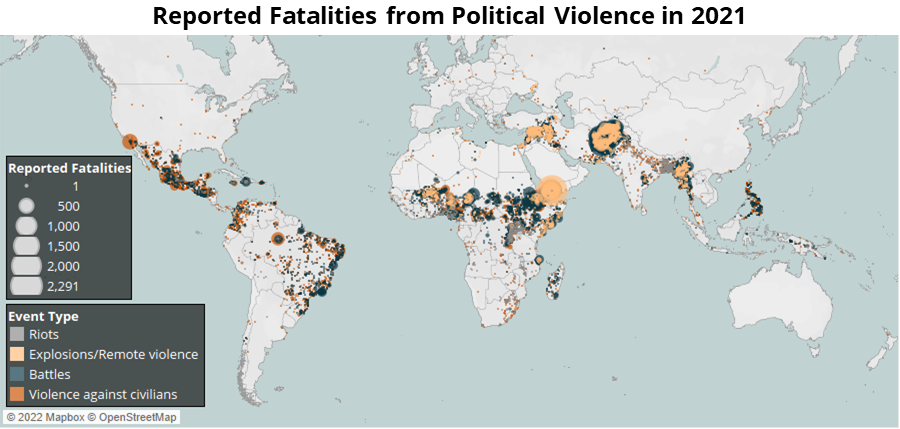

In contrast to the slight overall decrease in political violence events, reported fatalities surged in 2021, increasing by 12% — or 15,740 fatalities — compared to 2020 (see Figure 3), indicating that political violence became even more lethal last year.

Figure 3. Reported fatalities from political violence in 2021

When compared with 2020, political violence in 2021 was deadlier in every region save for Europe and the Middle East (see Figure 4). In Central Asia and the Caucasus, 4,257 more fatalities were reported in 2021 — an increase of over 11% — despite the substantial decrease in political violence events. These diverging trends were driven by the end of the six-week war between Armenia and Azerbaijan in 2020, combined with the increased lethality of fighting in Afghanistan in the lead-up to the Taliban takeover of the country in 2021.

Figure 4. Reported fatalities from political violence by region (2020-2021)

In addition to being two of the most violent countries in the world (see Table 1), Afghanistan and Yemen also registered the highest numbers of reported fatalities in 2021. The countries home to the most reported fatalities from political violence in 2021 include: Afghanistan (42,220 fatalities), Yemen (18,385 fatalities), Myanmar (10,387 fatalities), Nigeria (9,875 fatalities), and Ethiopia (8,513 fatalities). Of these countries, only Yemen experienced a decrease in reported fatalities in 2021, coinciding with the overall decline in political violence events in the country – underlining just how deadly the war in Yemen remains in order to continue topping these lists. Myanmar and Ethiopia saw high fatalities as a result of the significantly worsening conflict environment in both countries (see Table 3).

Trends by Actor

A wide variety of actors engaged in political violence in 2021, spanning state — both domestic and international — and non-state groups, anonymous or unidentified armed agents, and spontaneous mobs. Although state engagement in political violence fell substantially — by 18% or 10,195 events — for the second straight year, state forces remained the dominant conflict actors globally in 2021. State forces engaged in 46% of all political violence events last year.

The prominent role played by state forces in political violence is linked to the fact that specific state actors continued to dominate the list of most active groups in 2021 (see Table 4), in line with trends seen in recent years. Even as conventional interstate wars become less common and non-state armed groups become increasingly sophisticated, state forces remain powerful and deadly conflict actors. Of the five most active groups in 2021, three are state forces: the Ukrainian military forces, the Afghan military forces operating prior to the Taliban takeover, and the Myanmar military junta. Additionally, the Taliban straddled the worlds of both rebel and state forces with their ascent to power in Afghanistan in August 2021.8 Since the fall of Kabul on 15 August 2021, the central Afghan government and its security forces have ceased to operate and control the country in a meaningful way. As the Taliban have been in de facto control of the country since 16 August 2021, they are now coded as the Government of Afghanistan by ACLED. This determination does not denote legitimacy or international legal recognition, but rather acknowledges the fact that a distinct governing authority exists and exercises de facto control over significant portions of territory in a country. For more on ACLED’s methodological decisions in the Afghan context, see this primer. Of these groups, the defeated Afghan military, the Taliban, and the Myanmar military were also involved in the deadliest engagements recorded last year – the former two underlining the lethality of violence in Afghanistan in the lead-up to the fall of Kabul, and the latter pointing to the lethality of civilian targeting in Myanmar (explored in further detail in the following section). While most of these groups reduced their activity in 2021, the Myanmar military increased its activity more than any other actor in the world last year.

Table 4. Actors participating in the highest number of political violence events in 2021

| Actor | Actor type | Primary country of operation | Number of events | Change in the number of political events since 2020 | Main event type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taliban/ Military Forces of Afghanistan (2021-) | Rebel forces/state forces | Afghanistan | 7,222 | Decrease of 394 events, or 5% decline | Battles |

| Military Forces of Ukraine | State forces | Ukraine | 6,156 | Decrease of 915 events, or 13% decline | Explosions/ Remote violence |

| Military Forces of Afghanistan (2014-2021) | State forces | Afghanistan | 5,902 | Increase of 118 events, or 2% increase | Battles |

| NAF: United Armed Forces of Novorossiya | Rebel forces | Ukraine | 5,522 | Decrease of 755 events, or 12% decline | Explosions/ Remote violence |

| Military Forces of Myanmar | State forces | Myanmar | 3,959 | Increase of 3,145 events, or 386% increase | Battles |

Other actors that significantly increased their conflict activity last year are presented in Table 5. The increase in Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA) activity alongside that of the Myanmar military is emblematic of wider fighting between the military and ethnic armed groups, particularly in Kachin and Kayin states. Meanwhile, the sustained rise of Turkish military and PKK clashes in Iraq, and a spike in Israeli military activity in Palestine, played substantial roles in these countries also registering some of the largest increases in violence in the world (see Table 3).

Table 5. Actors with the greatest increase in activity in 2021

| Actor | Actor type | Primary country of operation | Difference in number of events since 2020 | Percent increase since 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Military Forces of Myanmar | State forces | Myanmar | 3,145 | 386% |

| Military Forces of Turkey | Other/External forces | Iraq | 905 | 42% |

| Military Forces of Israel | Other/External forces | Palestine | 861 | 116% |

| PKK: Kurdistan Workers Party9ACLED does not collect information on the perpetrator of violence given the biases associated with such reporting. This means that this table includes those actors who are involved in the greatest increase in violent activity, whether or not they were the perpetrator. The PKK, for example, has been the target of a number of new operations by Turkey, which contributes to its position in this table. | Rebel forces | Iraq | 848 | 74% |

| KIO/KIA: Kachin Independence Organization/ Kachin Independence Army |

Rebel forces | Myanmar | 618 | 1,766% |

All types of conflict actors increased their activity overall between 2020 and 2021, except for state forces and external/other forces (see Figure 5). Activity involving external/other forces fell by nearly 5% — or 505 events. The reduction in this activity was mostly driven by decreases in cross-border clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan, India and Pakistan, and the withdrawal of international forces from Afghanistan.

Figure 5. Political violence involvement by each actor type (2020-2021)

Contrastingly, both political militias and rebel forces significantly increased their engagement in political violence in 2021. Political militia activity rose by more than 9% — or 3,257 events. The proliferation of activity involving a large array of armed groups fighting against the military in Myanmar was largely responsible for this growth. ACLED records hundreds of new local defense groups or resistance forces operating in opposition to the military junta in 2021.

Rebel engagement in political violence increased by nearly 5% — 1,453 events — as a diverse range of rebel groups increased activity across significantly different circumstances. Increased rebel activity was recorded in countries suffering from fresh outbreaks of civil conflict, like Myanmar and Ethiopia, as well as countries suffering from long-running Islamist insurgencies, such as Burkina Faso and Somalia. Meanwhile, in Iraq, increased rebel activity was driven by Turkish forces launching offensives against the Kurdish PKK.

Threats to Civilians

Political violence targeting civilians increased in 2021, with deadlier consequences than 2020. ACLED records a 12% rise (3,854 events) in civilian targeting overall last year, with 33,331 events reported in 2020 compared to 37,185 in 2021. Whereas civilian targeting made up 35% of all political violence in 2020, this increased to nearly 40% in 2021. Civilian fatalities also increased — by 8% (2,759 fatalities) — with 35,879 reported fatalities in 2020 compared to 38,658 in 2021.

Civilians continued to come under attack across diverse contexts and by diverse actors in 2021: they were the targets of both belligerents in large-scale conflicts, as in Syria and Myanmar, and gangs engaging in turf wars in Mexico and Brazil. In other spaces, civilians faced multiple overlapping and concurrent threats. In Nigeria, for example, civilians were the targets of persistent mob violence and communal conflict, as well as an Islamist insurgency in the northeast and a separatist conflict in the southeast.

Civilians also continued to face a variety of different forms of violence, perpetrated by a wide array of actors in 2021, as depicted in Table 6. In many contexts, these threats remained the same as in 2020: gang violence, particularly by anonymous or unidentified gangs, accounted for the most direct attacks on civilians in Mexico last year. Similarly, anonymous or unidentified armed groups were again responsible for the majority of sexual violence events reported in the Democatic Republic of Congo (DRC). In India, violent mobs continued to target civilians. In Syria, the threat of abductions and forced disappearances by the Syrian Democratic Forces (QSD) continued to rise,10Unless arrests are carried out extrajudicially, they are not coded as Abductions/forced disappearance in ACLED data, and rather are coded with sub-event type Arrests (in certain cases, state forces may carry out arrests extrajudicially; in such cases, their actions would hence be coded as Abductions/forced disappearance.) As such, arrests made by the Syrian regime are not included under forced disappearances here. ACLED codes at least 108 arrest events by regime forces in 2021; each event can involve the arrest of more than one person. For more on ACLED methodology, see the ACLED Codebook. while the detonation of remote explosives, landmines, and IEDs by anonymous or unidentified armed groups remained a persistent threat. Meanwhile, unidentified or anonymous groups continued to target civilians with grenade attacks in Iraq. In Afghanistan, the military launched airstrikes against civilian targets as they fought a losing war against the Taliban.

Table 6. Civilian targeting by sub-event type in 2021

| Event type | Sub-event type | Number of events targeting civilians across all countries of ACLED coverage | Number of fatalities stemming from these events | Countries where this violence is most common | Primary perpetrator of this violence in this country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violence against civilians | Attack | 23,881 | 32,500 | Mexico (5,505 events, 6,723 reported fatalities) | Anonymous or unidentified gangs (5,281 events, 6,459 reported fatalities) |

| Abduction/ forced disappearance |

3,525 | 011 This sub-event type is used when an actor engages in the abduction or forced disappearance of civilians, without reports of further violence. If fatalities or serious injuries are reported as a consequence of the forced disappearance, the event is coded as ‘Attack’ instead. Therefore, by ACLED methodological definition, no fatalities occur in such events, or else they would have been coded differently. For more on ACLED coding decisions, see the ACLED Codebook. | Syria (850 events, 0 reported fatalities) | QSD: Syrian Democratic Forces (591 events, 0 reported fatalities) | |

| Sexual violence | 365 | 236 | Democratic Republic of Congo (62 events, 63 reported fatalities) | Anonymous or unidentified armed groups (27 events, 3 reported fatalities) | |

| Explosions/ remote violence |

Chemical weapon | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Air/drone strike | 336 | 642 | Afghanistan (91 events, 106 reported fatalities) | Military forces of Afghanistan (79 events, 90 reported fatalities) | |

| Shelling/artillery/missile attack | 979 | 1,048 | Yemen (266 events, 208 reported fatalities) | Operation Restoring Hope (121 events, 74 reported fatalities) | |

| Remote explosive/ landmine/IED |

2,106 | 1,979 | Syria (403 events, 393 reported fatalities) | Anonymous or unidentified armed groups (358 events, 350 reported fatalities) | |

| Suicide bomb | 22 | 279 | Somalia (8 events, 78 reported fatalities) | Al Shabaab (8 events, 78 reported fatalities) | |

| Grenade | 215 | 144 | Iraq (41 events, 4 reported fatalities) | Anonymous or unidentified armed groups (36 events, 3 reported fatalities) | |

| Riots | Mob violence | 4,166 | 1,130 | India (572 events, 102 reported fatalities) | Mobs (572 events, 102 reported fatalities) |

| Violent demonstration | 1,006 | 50 | South Africa (193 events, 31 reported fatalities) | Rioters (193 events, 31 reported fatalities) | |

| Protests | Excessive force against protesters | 581 | 650 | Myanmar (218 events, 373 reported fatalities) | Military forces of Myanmar (187 events, 358 reported fatalities) |

In some cases, while threats remained the same, the consequences were far deadlier in 2021. In Somalia, for example, Al Shabaab killed more than twice as many people in suicide bombings against civilian targets in 2021 than in 2020.

In other cases, though, new threats both emerged and became dominant in 2021. In Yemen, while Houthi forces reduced shelling against civilian targets in 2021, forces that were part of the Saudi-led Operation Restoring Hope more than doubled their shelling of civilian targets.12 For more on methodology decisions in the Yemeni context, including in regard to reporting by Saudi sources, see this primer. In Myanmar, following the coup in February 2021, the military engaged in a deadly campaign targeting anyone opposed to the takeover, killing more than 300 peaceful protesters – making it the deadliest place in the world for demonstrators. In South Africa, violent demonstrators targeted civilians at much higher rates than in 2020, driven by an outbreak of violent demonstrations following the arrest of former President Jacob Zuma in July 2021. Dozens of people were killed during the violence, prompted by Zuma’s arrest for contempt of court following his refusal to cooperate with investigations into alleged corruption during his time in office.

The countries with the highest levels of civilian targeting in 2021 are presented in Table 7. Mexico remained home to both the most violence targeting civilians and the most reported civilian fatalities in 2021, with violence targeting civilians increasing by 5% in the country compared to 2020. In fact, violence targeting civilians increased from 2020 to 2021 in all of the countries home to the most civilian targeting events.

Table 7. Countries with most civilian targeting in 2021

| Country | Number of events with direct civilian targeting | Change in the number of political events since 2020 | Number of reported civilian fatalities | Primary perpetrator of civilian targeting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 6,268 | Increase of 303 events, or 5% increase | 6,765 | Anonymous or unidentified gangs |

| Brazil | 3,262 | Increase of 240 events, or 8% increase | 2,863 | Anonymous or unidentified gangs |

| Myanmar | 2,564 | Increase of 2,072 events, or 421% increase | 2,240 | State forces (Military forces of Myanmar) |

| Syria | 2,517 | Increase of 258 events, or 11% increase | 1,628 | Rebel groups (including QSD: Syrian Democratic Forces)13Unless arrests are carried out extrajudicially, they are not coded as Abductions/forced disappearance in ACLED data, and rather are coded with sub-event type Arrests (in certain cases, state forces may carry out arrests extrajudicially; in such cases, their actions would hence be coded as Abductions/forced disappearance.) As such, arrests made by the Syrian regime are not included under forced disappearances here. ACLED codes at least 108 arrest events by regime forces in 2021; each event can involve the arrest of more than one person. For more on ACLED methodology, see the ACLED Codebook. |

| Nigeria | 1,580 | Increase of 347 events, or 28% increase | 3,710 | Identity militias (including communal militias in the north-central and northwest regions) |

In addition to Mexico, civilian targeting also increased in Brazil in 2021, by 8%. In both Mexico and Brazil, the increases were largely driven by gang violence, the majority involving unidentified or anonymous groups. In Brazil, the growing threat of civilian targeting has been particularly pronounced in the northern Amazonas state. These attacks have become more common as rival criminal organizations fight over control of drug-trafficking routes in the border states of Brazil.

Myanmar was home to some of the highest levels of civilian targeting globally in 2021, with the number of events in the country increasing significantly from 2020 to 2021. The military was the dominant threat to civilians in 2021, after seizing power from the elected government in February. The military used deadly force against anti-coup demonstrators and also carried out attacks on civilians who were unarmed and not involved in demonstrations, including shelling civilian targets. Members of the National League for Democracy (NLD) and other anti-coup activists have been detained and killed while in military or police custody. As military violence increased, military-linked administrators, party officials, and military informers were targeted by resistance groups and unidentified assailants in both remote and direct attacks for the role they are perceived to play in supporting the junta.

The greatest increases in civilian targeting were recorded in Myanmar, Palestine, Colombia, Nigeria, and Burkina Faso. In Myanmar, this was driven by the military junta and its attacks on civilians and opposition. In Palestine, civilians were heavily targeted by both rioters and Israeli forces during the dramatic escalation in political violence that hit the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in May 2021. In Colombia, increased civilian targeting has coincided with intensifying contestation between numerous active armed groups in 2021; while an increasing number of attacks were reported in Norte de Santander, Valle del Cauca, and Antioquía, Cauca remains one of the areas of greatest risk for civilians. In Nigeria, the worsening threat to civilians was particularly pronounced in north-central and northwest states — including in Kaduna, Niger, Zamfara, and Sokoto — where militias engage in cattle rustling, kidnapping for ransom, and pillaging of villages. In Burkina Faso, civilians bore the brunt of the deepening JNIM insurgency in 2021.

Around the world, anonymous or unidentified groups were responsible for the most violence targeting civilians last year, accounting for 45% of all events (see Figure 6). Tracking only the violence perpetrated by known, named agents would therefore obscure the full scope of threats faced by civilians, especially in contexts where unnamed groups are responsible for large proportions of civilian targeting. In many cases, anonymity allows for groups to act on the behalf of elites who stand to benefit from such violence. Anonymous or unidentified actors in Mexico, Brazil, Syria, and Myanmar, specifically, perpetrated the highest number of civilian targeting events last year.

Figure 6. Perpetrators of violence targeting civilians in 2021

Of identified actors, state forces were the dominant perpetrators, responsible for 16% of all civilian targeting and 14% of all reported civilian fatalities last year. They were followed by rioters and violent mobs, which were responsible for 14% of all civilian targeting but only 3% of all civilian fatalities. Contrastingly, rebel groups were responsible for 16% of all civilian fatalities, despite only accounting for 11% of civilian targeting. This is indicative of the differing risks to civilians presented by different actors. While rioters and violent mobs may target civilians more frequently, rebel groups pose a much more lethal threat.

Among named actors, the perpetrators responsible for the most civilian targeting in 2021 include the Myanmar military, the QSD in Syria, the Houthis in Yemen, the former military of Afghanistan, and the Al Qaeda-affiliated JNIM in the Sahel. Some of these groups — including the Myanmar military, QSD, and JNIM — were also among those that most increased their targeting of civilians over the past year.

Political Violence Targeting Women in Politics

Physical violence targeting women in politics has been increasing in most regions of the world. Women in politics include women politicians, candidates for office, voters, political party supporters, government officials, and activists/human rights defenders/social leaders. Such violence poses an obstacle to women’s participation in political processes.

Numerous countries saw an increase in such violence last year, including many of the countries home to significant levels of political violence more generally. Mexico, for example, is where civilians continue to face the greatest risk – and is also where women in politics face the most significant threat. Like civilian targeting, which further increased last year, targeting of women in politics also increased in 2021. Women candidates for office face particularly high risks of violence, especially at the hands of anonymous armed agents, who often target candidates and politicians as a means to influence local politics, especially in cases where a candidate might pose a threat to lucrative criminal activity, such as drug trafficking.

Myanmar, home to the greatest increase in civilian targeting last year, is now one of the most dangerous places for civilians in the world. Attacks on women engaged in the political sphere also rose last year, especially attacks on government officials and political party supporters. State forces have also targeted women leaders of the anti-coup protest movement, who were often on the front lines of the demonstrations – despite the military junta’s violent crackdown on protesters.

Colombia, also home to one of the greatest increases in civilian targeting last year, is another country where women in politics are at high risk of violence – and where such targeting increased in 2021. There, women activists, human rights defenders, and social leaders are under threat, especially in the departments of Norte de Santander and Cauca, with attacks often carried out by anonymous armed agents. Such targeting has increased since the start of the pandemic.

In short, the risks that women in politics face around the world vary in form, perpetrator, and targets, underscoring the importance of country-specific approaches in combating this targeted violence. While this violence may be impacted by the local political and conflict environment, it does not always mirror the threats faced by the civilian population at large.

Demonstrations

Trends in Demonstration Patterns

Demonstration activity increased by 9% — or 13,100 events — in 2021. In total, ACLED records 145,769 demonstration events in 2020 and 158,869 in 2021. The countries home to the most demonstrations include India, the United States, France, Italy, and Pakistan (see Table 8).

Table 8. Countries with the highest number of demonstration events in 2021

| Country | Number of recorded events | Change in the number of demonstration events since 2020 | % of demonstrations involving intervention by authorities | Primary driver(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 14,600 | Increase of 56 events or less than <1% | 7% | Anti-farm law and labor demonstrations |

| United States | 13,121 | Decrease of 9,196 events or 41% | 2% | Anti-coronavirus restrictions/right-wing mobilization |

| France | 8,446 | Increase of 3,189 events or 61% | 2% | Anti-coronavirus restrictions/anti-vaccine demonstrations |

| Italy | 7,444 | Increase of 1,886 events or 34% | 1% | Anti-coronavirus restriction/anti-vaccine demonstrations |

| Pakistan | 6,904 | Decrease of 1,257 events or 15% | 2% | Labor demonstrations |

ACLED records the highest number of demonstrations last year in India — 14,600 events — with approximately the same number of demonstrations as reported in 2020. The farmer-led anti-farm law demonstrations remained one of the dominant drivers of demonstration activity in the country throughout 2021. The farmer movement developed in 2020 in opposition to a series of government agricultural reforms aimed at deregulating the sale and pricing of farm produce. Farmers feared it would erode state subsidies and would leave farmers exposed to potential vulnerabilities under free-market conditions. On 9 December, Indian farmers announced an end to the demonstrations following the government’s repeal of the reforms — a rare successful outcome to a protest movement.

The United States continues to be home to numerous demonstrations, despite a significant decline in demonstration events in 2021 relative to 2020. A number of drivers contributed to this sustained mobilization, often involving the same protesters assuming new purposes or agendas: shifting from the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement, which punctuated the beginning of the year with the 6 January storming of the United States Capitol building; to opposition to vaccines and other pandemic-related policies; to challenging access to abortion or critical race theory. An increasing proportion of these demonstrations also continue to be armed and take place on legislative grounds – a worrying trend given the higher risk of these demonstrations turning violent or destructive.

France and Italy are included on this list as a result of significant increases in demonstrations driven in both countries by opposition to coronavirus-related restrictions (explored in further detail below). In Pakistan, labor demonstrations were the main driver in 2021, as labor groups responded to worsening inflation and unemployment, as well as rises in the prices of basic commodities.